Have you ever stopped to ponder the integrity of a plastic grocery bag? How such a thin material can support several pounds of apples, potatoes, jars of pasta sauce, a jug of orange juice — even a gallon of milk? It’s a wonder the flimsy sacks don’t spill their contents on the journey from the trunk of the car to the kitchen counter more often.

Hay binding is a similar feat of engineering, albeit at a much larger scale. Net wrap and baler twine configured out of plastic as thin as five-thousandths of an inch thick can hold the shape and support the weight of bales well over 1,000 pounds. Add in the explosive capabilities of densely baled forage and the proper selection and use of hay binding becomes that much more critical to safe handling and storage.

Choosing the right type of hay binding extends beyond the physical strength of net wrap or baler twine, though. Round bales can be bound by either product, depending on the harvest machinery on the farm, whereas square balers are inevitably set up for twine. Unit price and cost efficiency are among the other factors to consider before buying a season’s worth of binding. Even more important is the forage species and the end-use of the hay being baled.

This is what Mike Schon calls the “application” of hay binding, or the way it will be used to package, store, and feed out bales to meet consumer and market demands. The vice president of sales and marketing for Bridon USA, an agricultural baler twine and net wrap manufacturing company based in Dubuque, Iowa, believes identifying the application of hay binding will not only point hay producers toward a specific product, but also inform the best practices to achieve their goals.

“Are you going to store bales inside or outside? For what amount of time? Will it be fed in three months or 12 months? How explosive is the type of forage in your environment?” Schon prompted. “Choosing hay binding is all about the application of it and what the farmer is going to use it for and if they are going to push the envelope.”

Net wrap has an edge

Net wrap typically outshines baler twine when it comes to efficiency. For example, if a baler turned four times to apply four layers of net wrap to a round bale, it would need to turn up to 30 times to put on an equivalent amount of twine. John Hilgart, a regional sales manager with Bridon USA, noted these extra revolutions could take up to one minute longer per bale to complete.

“One minute doesn’t sound like a lot, but you can go from averaging 25 to 30 bales an hour with twine to averaging 45 to 60 bales an hour with net wrap. If you take that over a five- or six-hour day, you can make up to 180 more bales using net wrap,” Hilgart said.

Net wrap also offers hay better protection because of its ability to shed water, which is especially crucial for bales that are stored outside. Picture the flat end of a 5-foot round bale with a red circle painted around the outer 6 inches of its face. This painted layer of hay is the most susceptible to weathering, and it represents up to one-third of the bale’s total volume. Without proper protection from the elements, a bale can experience significant dry matter loss.

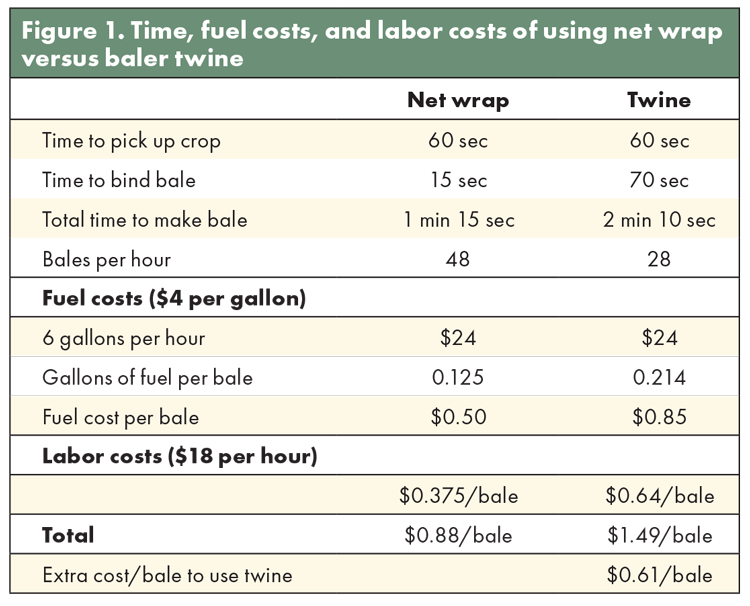

Moreover, moisture-wicking net wrap safeguards forage quality that would otherwise diminish if bales got wet. This added protection and better efficiency often comes at an additional cost, but Hilgart said it is an investment that pencils out to higher profits overall. Net wrap enables farmers to make the same number of bales using less fuel and less labor in less time compared to twine, which all translate to greater savings.

“A lot of people think it’s cheaper to put on twine because the product itself costs less, but then we look at how we are using much less fuel per bale, fewer man hours per bale, and creating less wear and tear on our equipment with net wrap,” Hilgart stated. “It may cost slightly more upfront, but it actually costs about 60 cents less per bale to use net wrap than twine.”

Knot strength and tail length

Despite the niceties of net wrap, many round balers are set up for twine, and twine is the default binding option for square bales. These polypropylene or sisal strands are categorized by knot strength, which is essentially a measure of tensile strength, or the maximum load a material can withstand without breaking.

The higher the bale density — and the larger the bale — the greater the knot strength required to contain forage. Mismatching knot strength with bale density and size could lead to what Schon and Hilgart refer to as “pain points” in the field, or broken knots, misties, and bales that fall apart altogether.

“It goes back to application,” Schon said. “There is a difference between the most intensive baling conditions and the most efficient. If you want twine that will hold up when you try to make a bigger bale or need to pack bales more densely to fit travel restrictions, you might have to increase your knot strength to achieve that.”

Some forage species require stronger knot strengths as well. For instance, alfalfa tends to be relatively easy to bale and hold together with twine, whereas crops like wheat straw and bermudagrass can put up more of a fight to stay bound.

“Think about if you took a handful of drinking straws and squeezed them together,” Hilgart explained. “The second you let go of the straws, they are going to release and expand again, and that is what wheat straw and bermudagrass want to do in a bale.

“Crops like that generally need a higher knot strength because even though these bales would weigh less than alfalfa bales of the same size, there is much more compression in wheat straw and bermudagrass, so it takes greater strength to hold that forage intact,” he continued.

Another descriptor of baler twine to deliberate is tail length. Longer tails are more forgiving when bales stretch and expand in the same way longer shoestrings are less likely to come untied when the laces are pulled tight. Similar to knot strength, this becomes more important when baling more compressive forages, like wheat straw.

Net wrap and baler twine have their differences, but both are available with variable degrees of ultraviolet (UV) protection. Without it, hay binding is subject to solar degradation, which threatens forage quality preservation and can present challenges to bale handling and transport.

“Those products, which are holding bales together when you pick them up to put in the feeder or on a truck for transport, start to deteriorate without an appropriate amount of UV protection. In a very short period of time, those bales will start to fall apart,” Schon asserted.

“As soon as that net wrap, in particular, starts to break down, it’s not shedding water as well. Water will start to penetrate the bale, and we can lose the quality of that outer one-third of bale volume within a few months,” Hilgart added.

Selecting the right type of hay binding may seem like a small step in the haymaking process, but it is one that must be approached from many angles. Producers can make the most of their investment by understanding the application of net wrap or baler twine and knowing how the aspects of each option will serve their operation. Next time you make a bale — or pick up a plastic grocery bag — consider the value of what’s inside. Then, take a minute to assess the product that you chose to contain and preserve the contents.

This article appeared in the July XL 2024 issue of Hay & Forage Grower on pages 26-27.

Not a subscriber? Click to get the print magazine.