Sugarcane aphid damage can be minimized |

| By Kay Ledbetter |

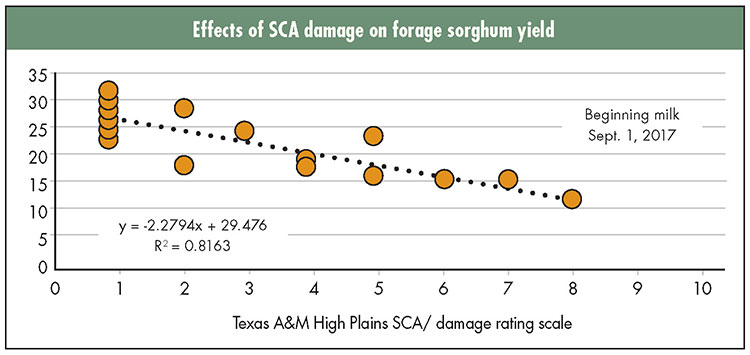

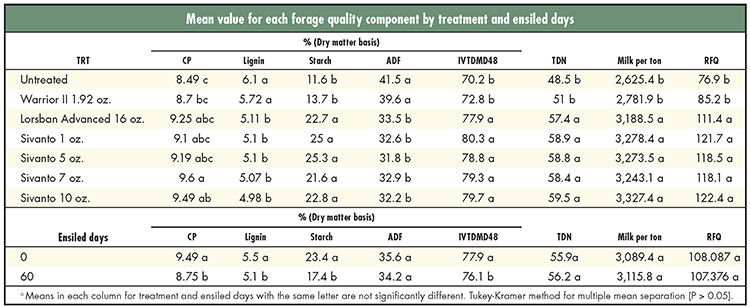

The author is a communication specialist with Texas A&M AgriLife Research and Extension.  Sugarcane aphid populations can build rapidly and devastate a forage sorghum crop. Scientists are looking for solutions. Texas A&M University Dairy and feedlot cattle operations across the Southern Great Plains have high demand for large quantities of quality silages annually. Historically, corn silage has been the predominant silage crop, but due to declining well capacities and pumping restrictions, there are growing opportunities for sorghum to take a greater share of the silage acres. Ed Bynum, AgriLife Extension entomologist, and Jourdan Bell, AgriLife Extension agronomist, both in Amarillo, conducted a field trial to evaluate the damage potential of sugarcane aphids (SCAs) to forage sorghum yield and silage quality. The research was funded by the Texas Grain Sorghum Board. SCA infestations in forage sorghum silages during the past three years have been extremely heavy, causing problems when cutting, but data on the actual amount of damage to silage yield and quality from these infestations was nonexistent, Bell said. “We often take the information from the damage potential of SCAs on yield reductions to grain sorghums and infer that the damage will be the same to forage sorghum silages,” she said. “However, with forage sorghums there is a need to determine the impact SCAs have on forage tonnage and silage quality at harvest and on feed quality after being ensiled.” In the trial, a commercial forage sorghum hybrid that is commonly grown for silage on the Texas High Plains was utilized. Insecticides with different levels of efficacy and an untreated check were used to create different SCA infestations and damage levels. Treatments included Sivanto Prime (5, 7, and 10 ounces per acre), Intruder (1 ounce per acre), Warrior II (1.92 ounces per acre), Lorsban Advanced (16 ounces per acre), and an untreated check. Sivanto Prime was used at three different application rates to induce levels of SCA control and damage. Warrior II is a pyrethroid that does not kill SCAs but will kill beneficial insects resulting in a rapid flare of SCA populations. Lorsban Advanced and Intruder are two insecticides that only suppress SCA populations for a few days. Infestation rates established The forage sorghum plots were checked weekly during July for initial infestations of SCAs. By the last week of July, no SCAs were found in the test plots, but they had been found in a producer’s forage sorghum trial that was 1 mile east of the trial field. Since the SCAs were close by, a decision was made to spray the high-rate Sivanto treatment plots on July 28 to prevent establishment of the SCAs and to try for possible aphid- and damage-free plots. By August 4, a few alate or winged aphids with small numbers of nymphs were starting to be found sporadically across plants. On August 16, SCA counts were taken to determine the variability of numbers among the plots. Sivanto provided excellent control of SCAs when a 10-ounce per acre rate was applied before they began to infest the field and when 5- and 7-ounce rates were applied at flowering before heavy aphid infestations, Bynum said. Both Lorsban Advance and Intruder delayed SCA populations from building for a week, Bynum said. This delay in population flare-up prevented substantial yield losses when sorghum was harvested at the soft dough stage. If the harvest date had been at a later growth stage, the yield losses may have been substantial.  A zero to 10 rating system was used with zero being no infestation or damage and 10 being 90 to 100 percent. The SCA density levels did not begin to cause significant increases in damage levels until September 1 in the untreated and Warrior treated plots, which had 5.75 and 4.5 damage ratings, respectively. The damage levels in these two treatments continued to climb and remained significantly higher than the other treatments from September 8 to 20. As the SCA densities continued building in the Intruder and Lorsban Advanced treatments, the damage ratings also increased more than ratings in the Sivanto treatments, but not as high as the untreated and Warrior ratings, he said. All of the Sivanto treatments equally prevented SCA densities from causing significant damage to the forage sorghum. Bell said the heavy infestations and damage from SCAs in the untreated and the Warrior treatment were the only treatments that saw a significant reduction in yield and percentage of plants lodged when compared among all of the treatments. Although infestations and damage levels began to be significant in the milk and soft dough growth stages in the Intruder and Lorsban treatments, these infestations and damage levels may not have occurred long enough to affect yield prior to harvesting on September 20, Bynum said. Plant height and dry matter at harvest were not affected by SCA infestations and damage among any of the treatments, Bell said.  Treating forage sorghum with the right insecticide and at the right time can be effective. Left: A field plot treated with Sivanto Prime at 10 fluid ounces per acre. Right: An untreated plot with heavy sugarcane aphid populations and damage Forage damage monitored When SCA infestations were high enough to cause damage levels ranging from 4.5 to 8 at the beginning of the milk stage, and pressure intensified to harvest, there were significant losses in yield, a higher percentage of plants lodged, and reduced quality of harvested forage, Bell said. The best linear relationship between damage and yield loss occurred at the beginning of milk stage and showed a 2.28-tons-per-acre loss in yield for each unit bump in damage rating between 2 to 8 (see graph). These results indicate substantial losses in yield and economic returns when SCA infestations cause heavy damage during the early grain filling growth stages before soft dough, she said. “While we have previously documented a direct correlation between higher SCA damage and lower forage quality at harvest, we have never evaluated the effect of SCA damage on silage quality,” Bell said. “The harvested forage was ensiled for 60 days, and the quality of the ensiled forage was compared to the quality of the forage at harvest.” Crude protein, lignin, starch, acid detergent fiber (ADF), and in vitro dry matter digestibility (IVTDMD) were affected by insecticide treatment and induced damage. All parameters were negatively affected by the damage created in the untreated and Warrior treatments, but there was no statistical difference between other insecticide treatments for the fresh forage. Calculated indices of forage quality, including total digestible nutrients (TDN), milk per ton, and relative forage quality (RFQ), provide producers an industry standard for forage comparison. At damage levels greater than 4.5, all three indices declined for the harvested forage, reflecting a significant reduction in the fresh, harvested forage quality (see Table). Crude protein (CP) and starch are important parameters depending on the end-user’s needs, Bell said. CP and starch levels were directly related to SCA damage and declined with greater damage due to to a lack of grain development. Quality loss continues “When evaluating the quality after ensiling versus the quality of the forage at harvest, we found that ensiling did not stabilize quality parameters,” Bell said. “Following an ensiling duration of 60 days, there was a significant reduction in lignin, IVTDMD, CP, and starch levels, indicating forage quality was not stable during the ensiling process.” The reduction in lignin, IVTDMD, CP, and starch may have been affected by the chop length of the forage. At damage ratings greater than 4, the forage chop length was not uniform. Irregular and long chop lengths do not pack well and trap oxygen, which can result in aerobic instability during the fermentation process and quality degradation. Calculated indices of forage quality (TDN, milk per ton, and RFQ) were not statistically different after ensiling for 60 days, she said. However, as with the fresh forage, quality indices also dropped as damage levels rose from 4 to 8. While forage quality is a concern for livestock feeders, farmers directly selling forage sorghum silage are more interested in the economic return of the fresh chopped forage, Bell said. If damage levels were greater than or equal to 6 by the soft dough growth stage, there were no losses in yield or economic return. However, when damage levels were 7 to 10, there was a progressive loss in yield and a substantial loss in the economic return. Bell and Bynum said the impact of SCA feeding damage to the forage silage quality components were similar to the losses related to yield. The forage quality in the untreated and Warrior treatments had statistically significant differences for all of the ensiled components, except CP and pH, when compared to the other insecticide treatments. “The results show that the level of damage SCAs cause to yield during the milk developmental stages to harvest impacts the quality of the forage sorghum,” Bynum said. “Since populations can develop rapidly, the study concluded SCAs should be controlled to prevent damage during the flowering and early grain developmental growth stages.” Ultimately, the quality of the silage is as good as the quality of the harvested forage, Bell said. When managing forage sorghums, timely SCA control measures are necessary in regions with sugarcane infestation to maintain fresh and ensiled forage sorghum quality.  This article appeared in the April/May 2019 issue of Hay & Forage Grower on pages 26 to 29. Not a subscriber? Click to get the print magazine. |