Don’t let 2019 be a barn burner |

| By Michaela King |

|

|

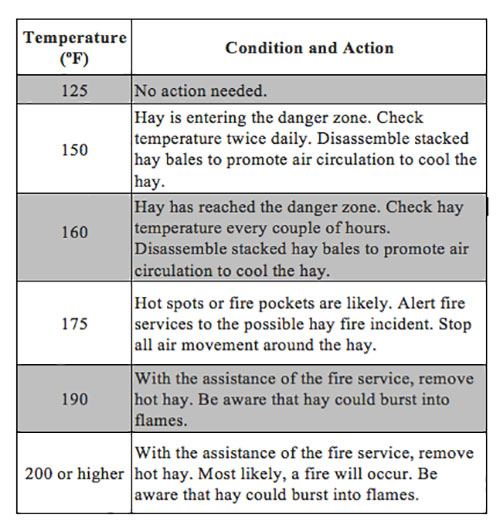

This spring has not been a kind one to farmers; it’s wet, and the forecast continues to call for more rain. Fields are being left unplanted, and hay is losing nutrition with each passing day. If current weather patterns continue, this sets up a scenario where hay harvest moisture is pushed to the limit or cut hay gets rained on. Do you bale wet hay with the risk of it heating and producing mold, or do you continue to let the nutritional value of the crop drop? For those who choose to cut and bale, the high-moisture hay is at risk for spontaneous combustion for up to three weeks after harvest. As mesophilic bacteria inside the bale reproduce, they release heat and cause temperatures to reach 130°F to 140°F. At this point, the best scenario is the bacteria die and the bale begins to cool. However, if thermophilic bacteria take over, temperatures can rise to over 175°F and fire pockets are likely to form. The best way to reduce the risk of fire is to bale under the right conditions. The ideal weather is a slight wind with humidity levels of 50 percent or less. This year, days with these conditions have been far and few between. Proper storage can also reduce the risk of hay fires. Factors such as volume and density of a bale stack and airflow between bales play a big role in lowering stored hay temperatures. Experts say bales with a lower density that aren’t stacked too deep and have good ventilation and airflow are at a lower risk of overheating. Checking at-risk hay If you are concerned hay may be baled too wet, monitor internal bale temperatures twice daily for six weeks after baling. Check internal temperatures at the center of the stack or around 8 feet down in larger stacks. One approach is to make a probe thermometer using a 3/4-inch pipe with the end closed into a point and 3/16-inch holes drilled into the bottom 4 inches. Lower a thermometer into the pipe using a string and leave inside the stack for 15 minutes to ensure an accurate reading. Another method for determining fire risk is sticking a 3/8-inch pipe into the stack twice a day. If the pipe is too hot to hold when removed, hay is at risk for fire. Take the proper safety precautions when checking the temperature of stacked hay. Use planks to disperse your weight in order to prevent falling into burned-out cavities, and if a harness is not readily available, make sure people are nearby to monitor the situation. Different temperatures, different risk According to experts, hay temperatures around 120°F to 130°F don’t cause fires, but they promote mold growth and lower the amount of protein available in the hay. Continued mold growth can raise temperatures to dangerous temperatures and once hay reaches 160°F to 170°F, alert the fire department immediately. At those temperatures, additional chemical reactions occur and the temperatures rise even higher. In a short period after this begins, spontaneous combustion normally occurs. If temperatures exceed 170°F, evacuate any livestock and machinery as safely as possible and call the fire department before attempting to move hay. The following chart, provided by the National Resource, Agriculture, and Engineering Service, is a good outline of the actions needed based on hay temperatures.  For additional information, visit Preventing Fires in Baled Hay and Straw  Michaela King Michaela King is serving as the 2019 Hay & Forage Grower summer editorial intern. She currently attends the University of Minnesota-Twin Cities and is majoring in professional journalism and photography. King grew up on a beef farm in Big Bend, Wis., where her 4-H experiences included showing both beef and dairy cattle. |