Cool, clean water boosts animal performance |

| By Mike Rankin, Managing Editor |

|

|

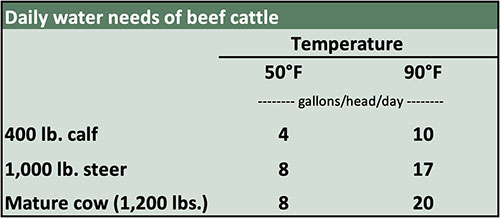

The shadows sway and seem to say tonight we pray for water, cool water. And way up there, He'll hear our prayer and show us where there's water, cool, clear, water. It was almost 80 years ago when the Sons of the Pioneers first recorded the epic hit, “Cool, Clear Water.” Many other singers have done the same since then. The desire for cool, clear water in the song can easily be compared to the need for cool, clear water for grazing livestock. Regardless of your grazing management skills or quality of your pastures, if cattle don’t have access to clean drinking water, animal performance on pasture will suffer. In a recent Auburn University webinar, Eve Brantley, a water specialist with Alabama Cooperative Extension, explained that beef cattle need between 7 and 20 gallons of water per day. Exactly how much depends on the dry matter of consumed forage, the season, and the physiological state and size of the animal. “Animals that are primarily grazing green forage won’t require as much water as those consuming dry hay,” Brantley said. “Also, higher temperatures can boost water consumption, but high humidity reduces daily intakes.” As summer approaches, providing adequate amounts of high-quality water becomes more critical if maximum livestock performance is to be realized. The table below indicates the range in cattle water needs based on size class and outside temperature. Note that there is more than double the requirement between 50°F and 90°F.  “Water consumption also elevates with age, weight, pregnancy, and lactation,” Brantley explained. “As a general rule of thumb, livestock need 2 gallons of water per 100 pounds of body weight each day.” Quality matters “We like to have cool, clear, good-tasting water, and livestock are no different,” Brantley emphasized. “The more water that livestock drink, the more feed they are able to consume. This results in more weight gain.” Brantley cited some research comparing cattle drinking clean water, pumped from a well, spring, or river, to those receiving water that was pumped from a pond or got their water directly from the pond. The animals receiving clean water spent significantly more time grazing and less time resting, loafing, and drinking. Water temperature is also an important component of potential consumption. Brantley explained that cattle prefer their water between 40°F and 65°F. If the water temperature is warmer than 80°F, consumption is reduced. “The water’s taste also comes into play,” Brantley noted. “Salinity, which includes levels of sodium chloride, magnesium, calcium, and sulfate, should be below 1,000 milligrams per liter (mg/L) to be considered safe to drink. Above this level, water intake will be limited, and animals will suffer from health effects such as diarrhea.” Nitrates in drinking water can also be a concern. Safe levels for livestock drinking water are below 100 mg/L. Nitrate levels that exceed 300 mg/L may result in severe health problems and possibly death. Brantley emphasized that it’s important to consider the nitrate levels in water as well as in their feed to ensure an acceptable total intake. “Nitrate is reduced to nitrite in the rumen,” the water specialist explained. “Nitrite limits the amount of oxygen that can be carried in blood. This becomes a bigger problem during drought, when summer annual grasses, bermudagrass, and johnsongrass can accumulate high concentrations of nitrates,” she added. Pathogens are also a concern if they find their way into water sources. These are often introduced through untreated animal waste. Pathogens, combined with nitrates in stagnant water, can trigger the formation and growth of harmful blue-green algae such as cyanobacteria. These algae produce toxins that can make cattle sick or, in a worse-case scenario, cause death. Brantley suggested that producers test their livestock’s water each year. This can be done through a reputable water analysis laboratory. Leave the ponds for fishing Brantley emphasized the importance of not letting pastured cattle loaf in ponds or wet soils. Infections from soil-borne bacterium, such as fusobacterium or foot rot, will likely occur with greater access to stagnant water and wet soils. Ideally, grazing cattle need to be fenced such that they don’t have access to ponds and streams. If they must have access, it should be limited by time and with a bank that is bolstered with rock so that mud holes don’t develop. A healthy streamside forest is also beneficial to protect surface waters; trees help to filter out pollutants before they reach the water source. Brantley said that pumping high-quality water to a tank or commercial waterer is preferred over the direct use of surface water sources. Many commercial waterers are designed not to freeze and allow for a minimal amount of water exposure to sunlight, which impedes algae development. If a water tank is infiltrated by algae and needs a good cleaning, Brantley suggested producers reference this Auburn University fact sheet, which offers step-by-step instructions for cleaning a tank. Cool, clear water. The song presumably made the Sons of the Pioneers a lot of money. The real thing can do the same for a livestock grazing operation.

|