Year-over-year hay stocks jump 37% |

| By Hay and Forage Grower |

|

|

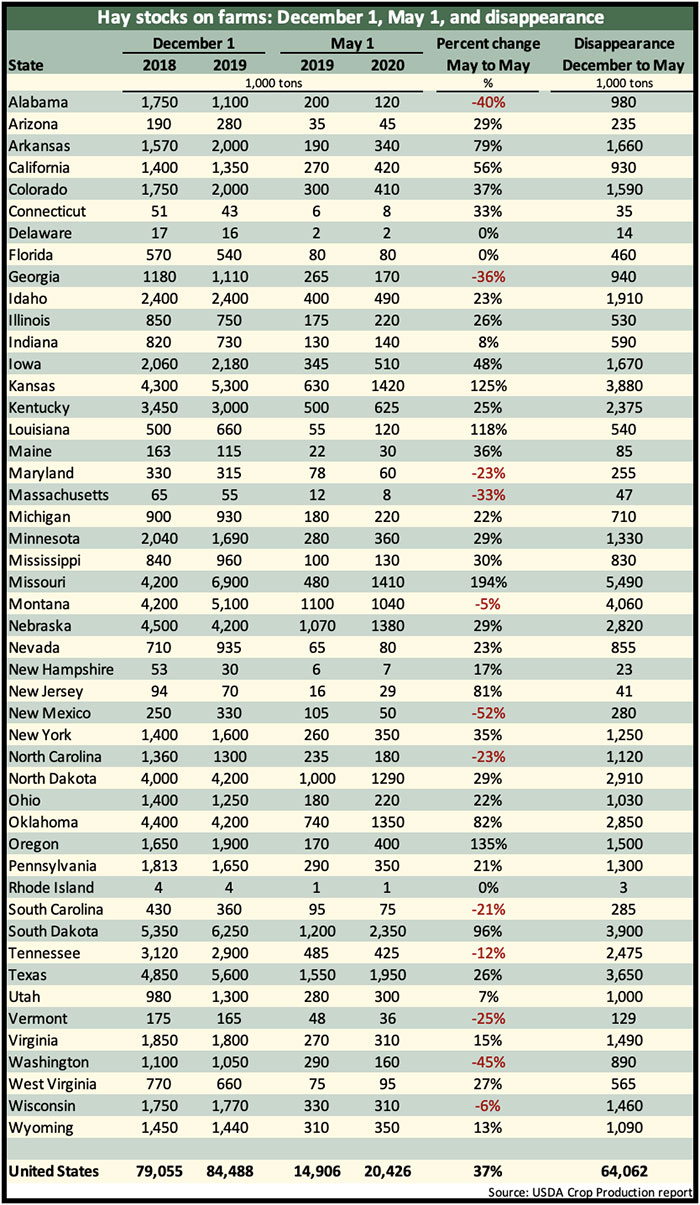

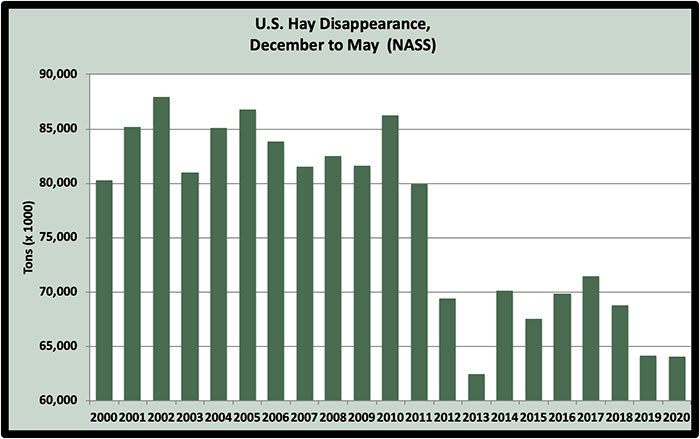

If the U.S. was a hay barn, then there are four bales today where three bales existed one year ago. Based on USDA’s Crop Production report released last week, May 1 hay stocks are 37% higher than last year. The boost in hay inventory this year follows a 3% reduction from May 2018 to May 2019 and a 36% decline from May 2017 to May 2018. Hay stocks currently stand at 20.4 million tons, about 5.5 million tons more than one year ago. This past December, year-over-year hay stocks also rose by nearly 5.5 million tons. At 20.4 million tons, May 1 hay stocks are still below 2015 to 2017 levels but are slightly above where inventories stood in May 2014.  Many of our largest hay-producing states had huge year-over-year May 1 stock increases (see table below). Falling into this group were: Missouri: up 194% Oregon: up 135% Kansas: up 125% South Dakota: up 96% Oklahoma: up 82% Arkansas: up 79% California: up 56% On the flip side, there were also some major hay-producing states with significant declines in inventories. This group included: New Mexico: down 52% Washington: down 45% Alabama: down 40% Georgia: down 36% North Carolina: down 23%  Hay disappearance Hay disappearance (primarily feeding) between December 1, 2019, and May 1, 2020, totaled 64.1 million tons. This is only slightly lower than last year and the lowest disappearance measure since 2013 (see graph). It’s the second lowest since 1985.  As we discussed last year at this time, it’s clear that a new normal has developed in terms of hay that moves out of the barn from December to May. Prior to 2012, disappearance from hay barns was always in the 80 to 85 million tons range. Since 2012, it’s been rare to have a year where disappearance exceeded 70 million tons, and during the past two years, hay feeding has been under 65 million tons. In other words, about 10 to 15 million fewer tons are being consumed from December through May, and that’s been occurring for the past eight years. Moving forward So, where does all of this leave us from a hay market perspective? What we know is that hay prices in most regions are currently $10 to $15 per ton lower than one year ago. That matches up with the higher May 1 hay stocks even though inventories are still not in a historically high range. It’s reasonable to expect that hay prices in 2020 will look more like 2018 than 2019. It’s going to take some time for the dairy and beef sectors to pull out of the damage caused by COVID-19. If this turns out to be an exceptional haymaking year for most regions of the country, we can expect hay inventories to rise as domestic demand simply won’t keep pace. It’s not all bad news (or good news if you’re a buyer) in the hay price arena. Export volumes during the first quarter of the year have been strong. This will help set the tone for prices in the West. More importantly, if it is a good haymaking year, that should translate into being able to make more high-quality hay; if there is one mantra in the hay industry that always holds true, good year or bad, it’s that quality hay sells. Finally, it’s always important to be reminded that hay markets are first and foremost a regional phenomenon. Local weather conditions and predominant enterprise types (dairy, beef, or equine) will ultimately dictate the price that your hay will bring. |