Forage crabgrass, Bob Dylan, and the changing times |

| By Michael Trammell, Twain Butler |

|

|

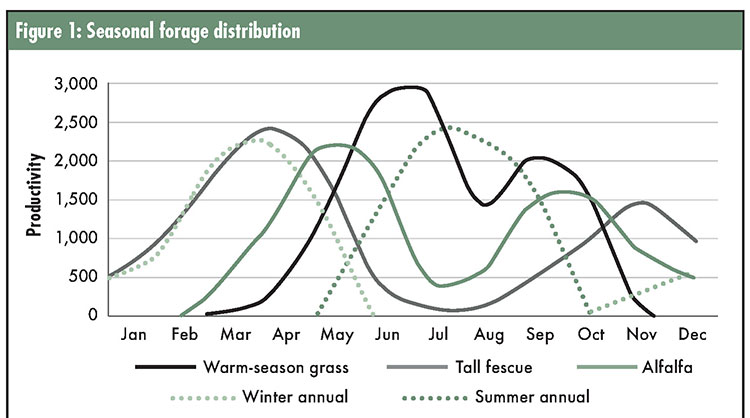

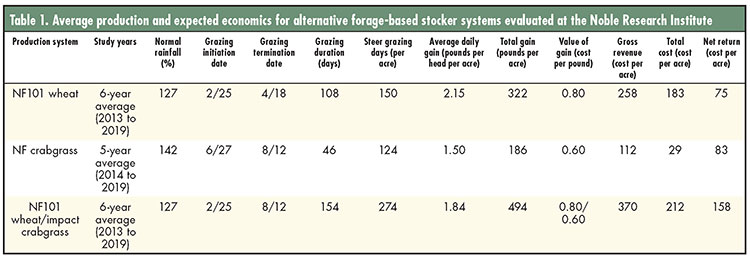

Trammell is a senior plant breeder and Butler is a professor and forage researcher. Both are with the Noble Research Institute. The improved Impact crabgrass (right) remains vegetative while Red River crabgrass (left) has already headed out. Crabgrass. Just mentioning the word can make some producers cringe and mutter disapproval while others smile and nod with appreciation. Crabgrass is an annual, warm-season grass that is fast growing, easy to establish, and capable of natural and prolific reseeding, all of which allows it to excel as a “weed.” Despite its bad reputation, crabgrass was originally used in Europe as fodder before being introduced into the United States, likely around the mid-1800s, as a forage for grazing livestock. During the past 30 years or so, there has been an enormous change in the perception of crabgrass with forage producers and agricultural academics. It is now considered a legitimate forage crop. While connotations are difficult to break and crabgrass still carries a stigma, as Bob Dylan once sang, “The times, they are a-changin’.” A history lesson There are differences between the weedy type and the cultivated type of crabgrass. Botanically, they are both in the genus Digitaria. The one most folks consider a weed is hairy crabgrass (Digitaria sanguinalis). The forage type we are discussing in this article is called southern crabgrass (Digitaria ciliaris). Even though southern crabgrass is a genetic variant of hairy crabgrass, botanical taxonomists recognize it as a separate species. Noble Research Institute has been conducting research on crabgrass for many years. In 1988, Noble was the first to publicly release a crabgrass cultivar, which was named Red River. During its history, Red River crabgrass became the main commercial cultivar, promoting the use of crabgrass as an important warm-season annual grass for forage and livestock operations. This initially occurred in the southern Great Plains but now has spread throughout the southern United States. However, a limitation of Red River was its early heading date, thus accelerating maturity and reducing the quality and quantity of late summer forage. Several years after the release of Red River, another crabgrass cultivar, Quick-n-Big, which exhibited even earlier flowering than Red River, was privately released with limited success. Recently, Noble Research Institute plant breeders have developed a new crabgrass cultivar called Impact. Impact crabgrass was released for forage livestock producers needing a later-maturing cultivar than Red River (see photo); one that is also broadly adapted, high yielding, and has improved nutritive quality and good reseeding ability. These improved crabgrass varieties are not weeds but high-producing, high-quality forages that are broadly adapted. The nutritive value of crabgrass is superior to other warm-season forage options during summer for both haying and grazing. Forage crabgrass has high crude protein and high digestibility, which promotes average daily gains of livestock that can easily reach 2 pounds per head per day. It is also an excellent choice in many double-cropping systems, especially with winter annual forages like wheat, to extend the grazing period. Widely adapted Crabgrass can be used in both till and no-till forage production systems and is often managed in many livestock grazing operations as a reseeding crop, thereby reducing the cost of seed and other annual costs. In addition, crabgrass can also be used as a component in warm-season annual and perennial forage systems. It is particularly productive in dryland situations, but it also performs well under irrigation and across a range of soil pH levels (5 to 7.5). It can be used for greenchop, silage or hay production, and is an excellent choice for conservation purposes. It covers critical areas quickly due to its rapid establishment and growth. Adequate fertility must be provided for forages to be successful, and crabgrass is no exception. Soil test and apply phosphorus and potassium accordingly. Nitrogen is usually applied at 75 to 100 pounds of actual nitrogen per acre for the growing season. Crabgrass seeds’ light and fluffy quality can interfere with its ability to flow through a seed drill. They are also rough in texture, resulting in individual seeds sticking together to form large clumps. The clumps not only cause problems when drilling but with the broadcasting of seed as well. To overcome these issues, crabgrass seed is sometimes mixed with a carrier, such as a fertilizer, to aid in seed flow through the machine when planting. Coated seed can also improve establishment results by adding bulk and weight to the seed, allowing it to be easily drilled or broadcast. For best results, seeding rates should range from 4 to 6 pounds of pure live seed (PLS) per acre and planting depth should be 1/4-inch deep. Crabgrass’ excellent ability to reseed makes re-establishment each year easy, which can potentially reduce costs; however, it is recommended to add low rates of additional seed annually to the production system. A good summer fit The ultimate goal for every forage producer is to have high-quality forage in sufficient quantity to feed livestock 365 days a year. Current research taking place at Noble Research Institute aims to develop year-round grazing systems for the southern Great Plains. Because no single forage can accomplish this (Figure 1), we are evaluating forage species in mixtures or in combination.  One of the crop rotations evaluated is a winter annual (NF101 wheat) and warm-season annual — specifically, the new Noble crabgrass cultivar named Impact. Based on forage availability, a put-and-take stocking method was used to measure grazing days, average daily gain, and total pounds of beef gain per acre. Using the expected performance data and expected prices for cattle and agronomic inputs, detailed agronomic budgets were developed that calculated revenues, costs, and net returns to the producer. Because of differences in the cattle market across years, system-generated revenue was normalized by assigning a common value of gain for each pound of beef produced. In the southern Great Plains, graze-out wheat systems are considered the standard. Incorporating crabgrass into this system can keep the ground covered to prevent soil erosion and provide relatively high-quality forage during the summer for stocker cattle. The six-year period had above normal rainfall, which resulted in excellent reseeding of the crabgrass. Cattle grazing crabgrass averaged 1.5 pounds per day average daily gain, which resulted in excellent gain per acre even though the grazing duration was limited in this system, since crabgrass was sprayed in August to facilitate wheat planting in early September. Overall net return to the producer was greater from the wheat-crabgrass system (Table 1).  Based on these data, crabgrass helps extend the grazing system in a winter annual system by filling the summer niche. Therefore, the next time you are looking for an annual forage to fit into your system, consider crabgrass. After all, “the times, they are a-changin’.” This article appeared in the April/May 2020 issue of Hay & Forage Grower on pages 30 and 31. Not a subscriber? Click to get the print magazine. Impact crabgrass with seed coating is marketed through Barenbrug USA in Tangent, Ore. |