From a small bag of seed |

| By C.J. Weddle |

|

|

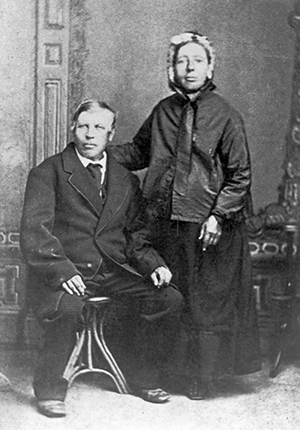

The author was the 2020 Hay & Forage Grower summer editorial intern. She currently attends Mississippi State University and is majoring in agricultural education, leadership, and communications.  Growing up on a row crop farm in Mississippi, the only experience I had with hay or forages was pitching small square bales onto a trailer. We baled a couple dozen acres of grass hay for the goat herd I established during my years of 4-H and FFA involvement. So how in the world did I end up with an internship focusing in hay and forage production? Well, that answer is simple. My academic adviser at Mississippi State University sent me an application link, and that began my journey into the world of hay and forage. While I did get to travel to numerous states interviewing farmers about how they produce and market hay and silage, grow forage crops for grazing, and keep up with industry changes, COVID-19 encouraged us all to spend more time at the office reading publications and watching webinars to source articles from. During my first week at Hay & Forage Grower, Managing Editor Mike Rankin plopped a blog on my desk and reported, “I’ve been wanting to write about this for a long time, and it’ll be a good way for you to learn about alfalfa, too.”  Wendelin Grimm with his wife Juliana. The couple moved from Germany to Minnesota in 1857. Grimm had many years of experience raising cattle and forages on his family’s farm in Külshiem, Germany, which is in an agricultural region of the country known for its lush alfalfa fields. His time on the farm taught him the benefits of alfalfa as cattle feed. When he moved his family across the ocean to Minnesota in 1857, he brought with him a single bag of alfalfa seed taken from his stock in Germany. He planted his first crop in the spring of 1858 and saw that it fared well over the summer months, but the harsh winter killed most of his initial stand. From the few surviving plants, Grimm collected seeds and repeated the process the following spring. He continued this exercise for 20 years, resulting in the first North American winterhardy variety of alfalfa. Not one kernel Grimm worked hard to develop stands that would survive the harsh Minnesota winters that killed so much of the other forage in the area. A neighbor’s remark in the summer of 1863 gave Grimm reason to be proud of his efforts. One day, Grimm drove his cattle past Henry Gerdsen’s home on the way to market. In a time when feed was scarce and most cattle in the area were very lean, Gerdsen was very surprised to see Grimm driving such fat cattle and asked him where he was able to find corn. Grimm replied, “Kein Körnchen, nur ewiger Klee.” (Not one kernel, only everlasting clover.) But what was so different about his alfalfa that allowed it to perform so well? Most people of the time chalked it up to the rich soil of Carver County. Although true, there were additional factors at play. Grimm’s alfalfa displayed physical traits, other than winterhardiness, which indicated it was a hybrid or different variety altogether than what was normally grown in the area. Long after Grimm’s death in 1890, many Midwestern university experiment stations compared Grimm alfalfa to other varieties trying to document its virtues. From farm to university The person responsible for bringing Grimm alfalfa to the attention of the agriculture industry was a schoolteacher who visited Carver County and learned of Grimm alfalfa’s superiority firsthand. Arthur Lyman had spent many years on his family’s farm convincing his father not to give up on alfalfa, and that persistence ended up paying dividends. After achieving success on his father’s farm, Lyman was very anxious to share it with someone who could further share Grimm alfalfa’s benefits with Minnesota farmers. In 1900, he met professor Willet Hayes, head of the University of Minnesota Agricultural Experiment Station. After their introduction, Hayes personally investigated the case of Grimm alfalfa. After a three-day tour guided by Lyman, Hayes committed to conducting Grimm alfalfa trials at the experiment station. Lyman worked closely with the professor on research that would prove the benefits of Grimm alfalfa. He secured the vast majority of the seed used in the trials and experiments. To supply as much as possible, he expanded his own alfalfa operation to over 100 acres. Weather conflicts prevented his seed harvest for nearly two years, but he still agreed to furnish seed not only for Hayes but for other experiment stations as well. After many years of hard work to prove the value of Grimm alfalfa, Lyman was invited to the annual meeting of the Minnesota State Agricultural Society where he presented a paper on Grimm alfalfa during a session on January 12, 1904. The most noteworthy comment of the discussion came from a member of the federal Department of Agriculture, William Spillman. “I cannot help but be impressed by this paper . . . we have been searching the world for a variety of alfalfa that would do just what this variety does. We sent a man to Turkestan this summer at great expense to get something of that kind, but here we know we have what we sought.” Research results Carefully recorded studies using genuine Grimm alfalfa seed, commercial seed, Turkestan seed, Iowa seed, and other unidentified varieties were replicated throughout the Midwest. Results from Montana and Kansas showed that Grimm alfalfa yielded three times as much hay as the varieties it competed against. Experiments in South Dakota produced hardy strains that would become widely known as S.D. 162. Professor Hayes was later appointed assistant secretary of agriculture. Charles Brand and Lawrence Waldron then dove into the genealogy of the marvelous, mysterious Grimm alfalfa. In the conclusion of their study, Brand announced that Grimm alfalfa was a natural cross between the common purple blossom alfalfa, Medicago sativa, and a wild yellow blossom species, Medicago falcata, which originated in Asia. Fast-forward to the present, most dormant alfalfa varieties currently grown can trace their taproots back to Grimm alfalfa. The legend lives on  Grimm’s farmhouse and a monument can be seen at Carver Park Reserve near Victoria, Minn. Although Grimm knew the nutritive and agronomic value of his alfalfa, he died before witnessing the impact his alfalfa would have on the livestock industry. However, during his lifetime, he helped his neighbors start their own stands by supplying them with seed and advice about the forage, which is why the majority of it was grown within a 10-mile radius of Grimm’s homestead for so many years. Sadly, Grimm did not document much of his work while improving his alfalfa, but his memory lives on through the stories recorded by his friends and family. According to local proprietor George Du Toit, the only time Grimm nearly suffered a complete loss to winterkill was during the winter of 1874 to 1875. In a written account, the Chaska, Minn., store owner noted that this was also the worst winter since the early 1840s. Grimm’s son, Joseph, remembered digging a driveway leading to a newly built barn on the homestead. He said, “The roots on this clover penetrated more than 10-feet deep through the clay soil.” The crop was credited with making Carver County the best dairy-producing county in the state by 1900. Today, alfalfa still earns a multitude of accolades. Coined the “Queen of the Forages,” it is ranked the third or sometimes fourth most valuable field crop in the U.S. — only behind corn, soybeans, and sometimes wheat. Grimm’s original homestead still stands in Carver County, Minn.; however, it is not in the possession of a Grimm descendant anymore. The family turned the property over to the Three Rivers Park District in 1962. Since then, it has been added to the National Register of Historic Places, undergone several grant-funded renovation projects, and opened to the public for viewing and recreation. 2020 issue of Hay & Forage Grower on pages 12 and 13. Not a subscriber? Click to get the print magazine. |