Burning away fescue ergovaline |

| By Josh Zeltwanger |

|

|

|

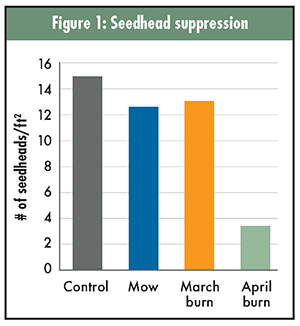

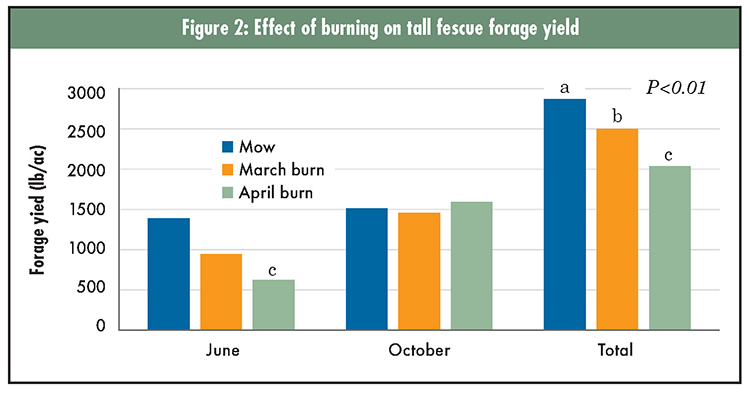

The author is a graduate student pursuing his Ph.D. in the Division of Animal Sciences at the University of Missouri.  Missouri researchers are using fire as a means to suppress tall fescue seedheads. Across the United States, livestock experience summer heat and the challenges it poses. During the summer, cow-calf and stocker operations in Missouri and much of the southeast United States see a sharp drop in cattle performance, including lower conception rates and average daily gains. This decline in performance is known regularly as the “summer slump” and is often tied directly to the forage source that grazing operations utilize. Tall fescue, a cool-season grass, is found on an estimated 35 million acres in the U.S., much of which resides in the Southeast. Tall fescue is infected with a fungus that produces ergot alkaloids, most notably ergovaline. Cattle that regularly consume infected fescue are compromised in their ability to dissipate heat properly. Subsequently, forage intake tends to decline, resulting in compromised performance as either lower weight gain or reproductive efficiency. Ergovaline tends to concentrate in the stems and seedheads of tall fescue, making these reproductive tillers a target for removal to improve cattle performance. What’s old is new again Although strategies to manage fescue toxicosis have been developed, adoption of these practices across the Fescue Belt has not been universal. Recently, research by our team at the University of Missouri has worked to develop low-cost strategies that limit seedhead growth in tall fescue pastures using prescribed fire. As a forage management tool, fire predates any of the current alkaloid mitigation strategies. Fire plays a part in sustaining healthy ecosystems across the world, as well as improving animal performance. By applying fire, the quality of forage consumed by cattle is improved. More importantly, burning fescue in the spring may prevent the development of seedheads. As fescue matures, alkaloid concentrations rise. Proportionally, greater amounts of alkaloids are present in the seedheads than in the rest of the plant. Therefore, we hypothesized that a spring fire application would limit seedhead development and impact ergovaline concentrations in tall fescue. To test our theory, we applied four different treatments to 40 plots (20 feet by 30 feet) located at the University of Missouri’s Southwest Research Center: 1. Control, no added management, 2. Mowing plots in mid-March, 3. Burning plots in mid-March, and 4. Burning plots in mid-April. The mow treatment was designed to mimic normal pasture conditions. Tall fescue pastures are commonly grazed short in the fall and over the winter. Monthly forage samples were collected to measure changes in alkaloid concentrations and forage quality. Additionally, seedhead prevalence was determined in May, and forage species composition was determined in May and October. The study was replicated in the spring of 2018 and 2019. Seedhead reduction  Applying fire in the spring may damage the vegetative tillers that have gone through the first stage of signaling. As a result, new tillers that grow to replace the damaged tillers will not be exposed to the first signal and are not capable of producing a seedhead. Other methods of seedhead suppression are available as well. The application of metsulfuron has reduced seedheads by more than 90% in previous research. Our mid-April burn reduced seedheads at a relatively high rate (up to 75%). Fire may have an advantage in cost and time investment. From this research, it is evident that timing fire is important, much like the application of metsulfuron. Currently, we are investigating different techniques for applying fire that could improve fire’s effectiveness against seedhead production. Given the reduction in seedheads, we wanted to see if this would lead to changes in alkaloid levels, specifically ergovaline. Generally, the plots burned in mid-March produced similar amounts of ergovaline as the control plots. The largest decrease was found in plots burned in mid-April, confirming that the decline in seedheads did indeed reduce alkaloid levels, specifically ergovaline. However, it is essential to note that we harvested whole plants out of all plots. Since the April-burned plots had fewer seedheads compared to the other plots, it is natural to assume that the differences in ergovaline were due to fewer collected seedheads. Reduced yield  An unfortunate consequence of alkaloid management is lower forage yield (Figure 2). The use of both mowing and chemicals to suppress seedheads have been shown to reduce forage availability in earlier research. In our experiment, forage availability declined by 22% in April-burned plots. This reduction in forage availability is in line with yield drag from metsulfuron applications to control seedheads. An important consideration in the reduced forage yield relates to the quality of the forage that is lost. If the forage not grown is mostly low-quality stems and seedheads, is there actually value in what did not grow? One direct contrast between herbicide application and fire for seedhead suppression in tall fescue pastures is the impact of herbicide on pasture legumes. Interseeding pastures with legumes like clover is a time-tested fescue strategy because enhancing diversity dilutes out alkaloids consumed by cattle. Improved plant diversity can also extend grazing seasons by providing different forages at different times throughout the year. However, metsulfuron-containing herbicides list clover species as plants affected by the herbicide. When we applied fire to the plots for two consecutive years, we noted no difference in the frequency of legumes in the plots. More research is needed on a larger scale, but it appears that fire is not harmful to legumes in tall fescue pastures. Anyone wishing to control tall fescue seedheads in a fescue-clover mix pasture should consider fire as an option. Fire is also used in other cattle production systems, such as the Flint Hills of Kansas. Ranchers there note a marked improvement in grazing cattle performance during the summer, which is related to improved forage quality, or at least removal of residue from the previous year’s growth. We noted small decreases in fiber content of burned plots during May, June, and July. Less fiber generally means higher quality forage. While fire may promote forage quality in tall fescue pastures, we regard it as a side benefit. Throughout the Fescue Belt, preparation for the summer slump has to start in late winter and early spring. Results from our research suggest that an early spring fire could suppress seedhead production in tall fescue pastures without negative impacts on legumes in the stand. Our group continues to focus on different techniques to apply fire and will soon evaluate cattle performance with grazing pastures that have been treated with fire. This article appeared in the November 2020 issue of Hay & Forage Grower on pages 18 and 19. Not a subscriber? Click to get the print magazine. |