Let crabgrass be your friend |

| By Deidre Harmon |

|

|

|

The author is an extension livestock specialist with North Carolina State University and is based at the Mountain Research Station near Waynesville, N.C.

In the last few years, crabgrass has quickly become one of my favorite forages because of its nutritive value, palatability, and versatility. My fascination for it started during my work as a graduate student at the University of Georgia. While at Georgia, my graduate research involved evaluating four warm-season annual forage systems for forage-finishing cattle. Cattle grazed treatments of sorghum-sudangrass, brown midrib sorghum-sudangrass, pearl millet, or a pearl millet and crabgrass mixture. There were three characteristics about crabgrass that really stuck with me following this project. First, I noticed that crabgrass acted as a complimentary forage, filling in all the bare spots between pearl millet plants. It really competed well with pasture weeds. Second, during dry periods and the drought of 2016, crabgrass was able to make use of small showers that barely moistened the top layer of soil. I presume that crabgrass, with its shallow root system and ability to root at each node on the plant, could make use of what small amount of moisture was available. Lastly, I found that not only was crabgrass easy to manage, but cattle would selectively graze the crabgrass first. I also saw this selectivity in other pasture systems where naturally occurring crabgrass was found. Collectively, my experience with crabgrass as a graduate student and the favorable characteristics that I observed during that time has really laid the foundation for crabgrass being a must-have species in my forage toolbox. In my travels around the state of North Carolina and across the Southeast, I often see many confused or disgusted looks on faces when conversing about planting crabgrass. Crabgrass has had a stigma of being a weed for many years. Not grandpa’s crabgrass Its negative stigma probably came from crabgrass’ persistence in cultivated crops, flower gardens, and manicured lawns and golf courses where it is an unwanted grass species. However, as a forage for livestock, it is a great option; consider yourself lucky if you find naturally occurring crabgrass on your farm. However, this naturally occurring crabgrass has not been selected for favorable forage attributes as our new or improved varieties have. The first improved variety of crabgrass was released in 1988 by R.L. Dalyrmple and the Noble Research Institute. This variety, called Red River, was selected for its yield potential and quality attributes. The variety was selected from a parent plant found growing in upland soils north of the Red River in Oklahoma. Since the release of Red River, we now have four other commercially available varieties of improved crabgrass on the market. A variety called Quick N Big was the second released variety by Dalyrmple and came on the market in 2006. Quick N Big is known to be an earlier maturing variety than Red River. Since then, Dalyrmple, also known as the godfather of crabgrass, has trademarked two other varieties called Quick N Big Spreader and Dals Big River. The Noble Research Institute has also released a variety called Impact in 2019 and sold the rights to Barenbrug, which is currently marketing the variety in a blend with Red River under the brand name Mojo. Crabgrass has been building momentum in the last couple of years, and I suspect that it is due to the raving reviews by those brave enough to try something “off the wall.” Improved varieties of crabgrass can produce as much as 5 tons per acre when moisture is not limited, and cattle will selectively graze it over fescue, bahiagrass, or bermudagrass. Forage from crabgrass is very palatable, highly digestible, and may be the easiest to manage of all the summer annuals. Seed for success Crabgrass forage ranges from 11% to 15.5% crude protein (CP) and 58% to 63% total digestible nutrients (TDN). Depending on where you live in the Southeast, the productive season is generally from May through October, though most of the forage will be produced in late summer. Crabgrass can be planted whenever the soil temperature reaches 65°F and can be drilled or broadcasted. Seed crabgrass at a rate of 4 to 6 pounds per acre from April through June and no deeper than 1/4 of an inch. Care should be taken when planting crabgrass to ensure that the seed flows through the drill or spreader. Uncoated crabgrass seed is light and fluffy and the seed often builds up static electricity, which causes it to cling to metal or plastic surfaces. Mixing lime, sand, or some other carrier that is uniform and of similar size to the seed in a 2:1 ratio with crabgrass seed can help ensure it will flow satisfactorily. Another desirable attribute of crabgrass is that it is a prolific seed producer, and, if managed properly, where seed is allowed to drop in late summer or fall, will build up a seedbank and reseed itself for the following year. Although we have little data on this practice, we have observed that planting crabgrass for several years in a row will help to build up the seed bank, and scratching or disturbing the surface in early spring will help the seed to germinate. This can be done with a disc harrow, drag, or other soil preparation tools. Questions to answer There are many reasons why crabgrass may be beneficial across a wide range of forage and livestock production systems. However, very little research has been done on this forage, especially when compared to more traditional forages such as alfalfa, bermudagrass, or tall fescue. As crabgrass continues to build momentum in the Southeast, we have set our sights in North Carolina on answering three simple crabgrass questions:

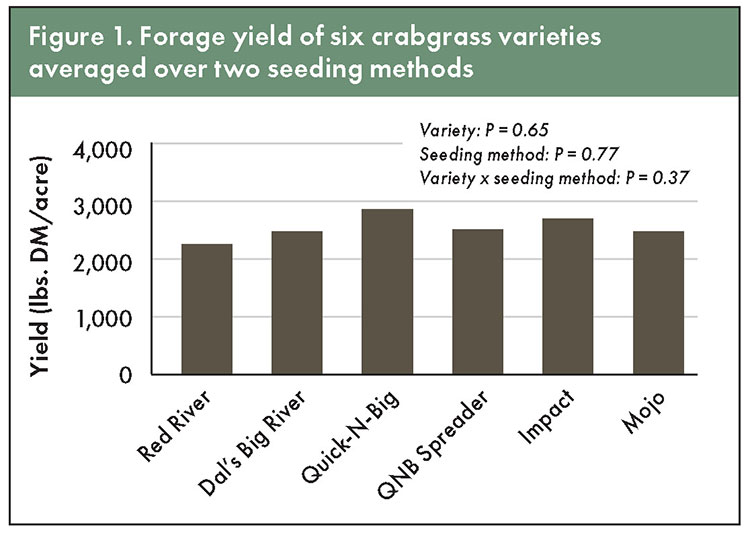

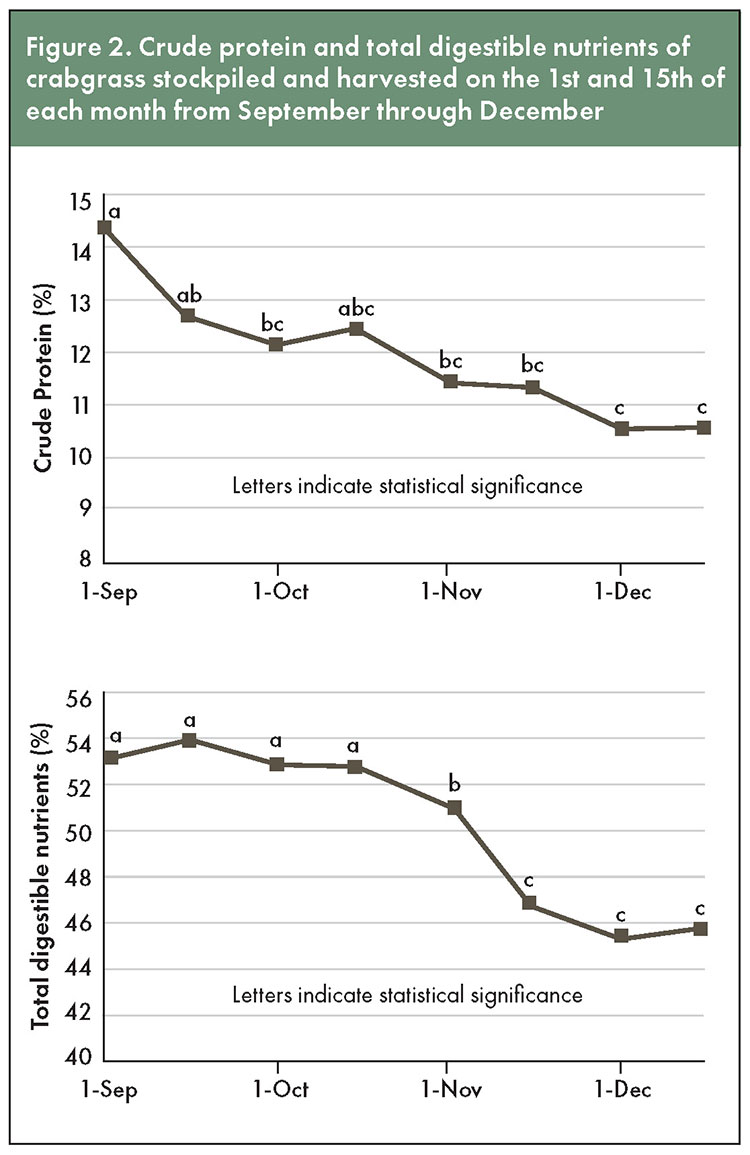

To answer the first two questions, a crabgrass variety trial was conducted at the Mountain Research Station in Waynesville, N.C., in the summer of 2020. Six crabgrass varieties (Red River, Dals Big River, Quick-N-Big, Quick-N-Big Spreader, Mojo, and Impact) were planted in small plots and either no-till drilled or broadcasted. The broadcasted planting method consisted of first rototilling the plots prior to broadcasting the seed, and then plots were firmed with a cultipacker to ensure good seed-to-soil contact. During the growing season, unfavorable and unusual cloudy and wet weather allowed for only one harvest of crabgrass, which likely impacted total yields. Nonetheless, there was no difference in forage yield among any of the crabgrass varieties (see Figure 1) The average yield equaled 2,525 pounds of dry matter per acre. Furthermore, crabgrass yields did not differ between broadcasting seed or no-till drilling.  Stockpiling potential The second project, a crabgrass stockpiling trial, came to fruition after visiting several farms that were interseeding crabgrass into existing and thinning tall fescue stands. Since cattle will selectively graze crabgrass instead of tall fescue, these producers were effectively stockpiling the tall fescue without removing any animals. We were interested in determining how long crabgrass could hold its value into the fall and winter months, and if it had the potential to be used for deferred grazing to help further stockpile fescue and extend the grazing season. This past fall, crabgrass forage was allowed to stockpile and was harvested on the 1st and 15th of each month from September through December. As expected, CP and TDN, along with several minerals, decreased from September 1 to December 15 (see Figure 2). At first harvest, the crabgrass forage contained 14% CP and 54% TDN, which would meet the energy needs and exceed the protein needs of a cow in mid-lactation. By the last harvest in mid-December, CP had dropped to 10.5% and TDN had declined to 46%. Even in December, crabgrass forage has the potential to exceed the protein needs of a cow in mid-lactation, but supplemental energy would need to be provided.  Crabgrass forage has great potential to extend the grazing season and provide nutrient-dense forage to livestock. If you are interested in trying something out-of-the-box that will have your neighbors with manicured lawns scratching their heads, then crabgrass is worth a try. We hope to continue our crabgrass research for several years and look forward to sharing future results. This article appeared in the April/May 2021 issue of Hay & Forage Grower on pages 30 and 31. Not a subscriber? Click to get the print magazine. |