Planning for Drought-Stressed Silage |

|

|

|

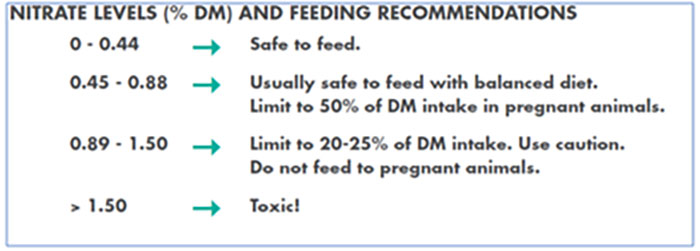

This item has been supplied by a forage marketer and has not been edited, verified or endorsed by Hay & Forage Grower.  Much of the Western and Southern United States were already in extreme drought conditions before summer officially started. Now it is time for producers to plan for harvesting and feeding their drought-stressed corn silage. “When drought occurs, I worry most about nitrate accumulation in the plant and potential heating and spoilage issues at feedout,” says Renato J. Schmidt, Ph.D., Forage Products Specialist, Lallemand Animal Nutrition North America. “We can still produce good silage from drought-stressed corn, maintaining the quality of the crop coming out of the fields, as long as the crop is harvested correctly, ensiled well and carefully stored.” Minimizing potential impact from nitrates during harvest Even subclinical nitrate toxicity can result in decreased intakes, weight gains, production and conception rates. Nitrate toxicosis can also cause embryonic death and, occasionally, abortions.1 Nitrates accumulate in the bottom third of the plant; therefore, producers could cut drought-stressed forage crops higher as management tool.2 Assess the degree of drought stress in the field. Sorghum and sudangrass hybrids, corn, pearl millet and cereal grains have high potential for nitrate accumulation. Then, harvest based on whole plant dry matter (DM) recommended ranges for the type of forage crop to be ensiled. Treating drought-stressed silage crops with a research-proven inoculant Drought-stressed corn tends to have low levels of lactic acid bacteria (LAB), which are essential to drive the initial fermentation process. These crops also tend to have higher levels of yeasts and molds and so are more prone to aerobic stability issues. Proven inoculants can help address both challenges. MAGNIVA® Silver or MAGNIVA Titanium can provide a fast, efficient fermentation, making up for the low natural LAB levels and maximizing nutrient recovery. MAGNIVA Titanium adds Lactobacillus buchneri NCIMB 40788 to the proven combination of Pediococcus pentosaceus 12455 with enzymes and to help achieve a fast front-end fermentation and maintain aerobic stability throughout storage and feedout. In fact, L. buchneri 40788 applied at 400,000 CFU per gram of silage or 600,000 CFU per gram of high-moisture corn (HMC), has been uniquely reviewed by the FDA and allowed to claim improved aerobic stability. The effect of ensiling on nitrates “The ensiling process itself can reduce nitrates by about 40 percent,” Dr. Schmidt advises. “However, it’s important to give ensiling time to work. Let forage ensile for at least three to four weeks. Then, introduce it gradually into the ration.” Testing for toxicity  Testing nitrate levels prior to feeding helps avoid toxicity. Silage can be incorporated at varying amounts depending on the results, but levels of 1.5% or greater should not be fed. Handling safely Producers should also be cautious when unloading silage made from corn with high nitrate levels. Nitrogen oxide gasses, which can be generated from nitrates during the first few days of ensiling, are lethal to animals and humans. Nitrogen oxide gases tend to accumulate in low areas and range from colorless to orange-brown. Dr. Schmidt notes these gasses are typically only a concern during the first few days of ensiling and tend to accumulate in low areas as they are heavier than air. To dissipate the gasses, run the blower for 15 to 20 minutes before entering an upright silo and use caution around vents in silo bags and when opening up a pile or bunker for feeding. “Dangerous gases can be produced during ensiling — even in crops that weren’t stressed at all,” Dr. Schmidt cautions. “It’s best to just stay clear of silos and piles for two to three weeks after filling. Always ventilate and wear an approved breathing apparatus. Safety should always come first!” |