A staggering alfalfa challenge |

| By Dan Putnam |

|

|

|

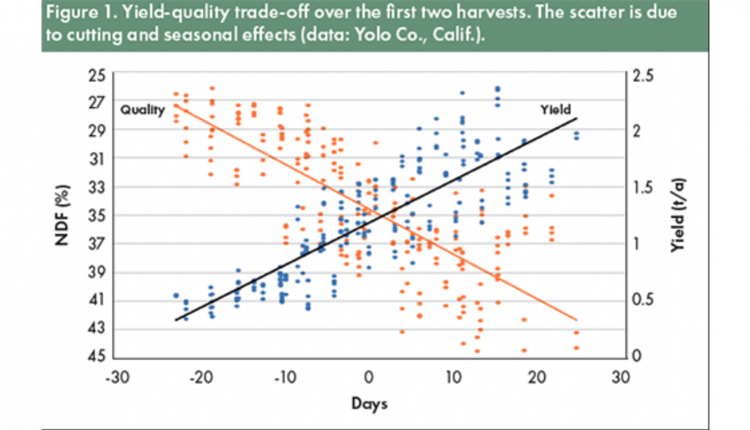

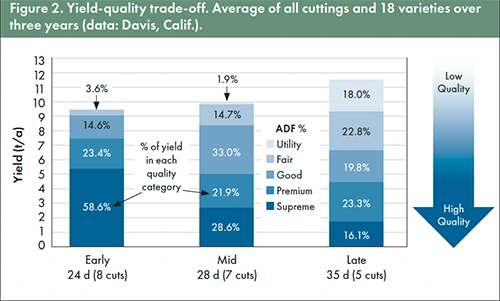

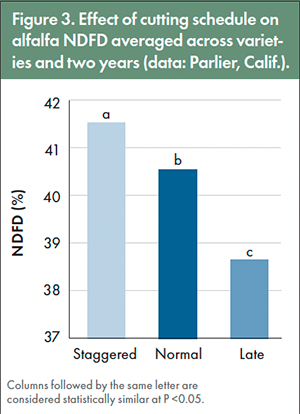

The author is an extension forage specialist with the University of California-Davis. Should I go for maximum yield or maximum quality? For generations, alfalfa growers have wrestled with this quandary. Although weather is a major factor, harvest schedule is often the most important determinant of both forage yield and quality. It is well known that high-quality alfalfa hay results in improved milk production. On the economic side, while price per ton is dependent upon quality, return per acre is largely affected by yield. Both are affected by maturity of the crop at harvest. Maybe some growers don’t care what their yields are and only want high quality, but I haven’t met one yet. Unfortunately, with alfalfa, rarely can yield and quality be maximized at the same time. High yields with delayed cuttings typically result in reduced quality, while harvesting early for high quality almost always results in lower yields.  The yield-quality tradeoff is a big challenge and an age-old problem for forage growers. A dataset where we harvested every few days over about 40 days in a farmer’s field illustrates this tradeoff in cuttings one and two in the Sacramento Valley of California (Figure 1). Yields within a growth period ranged from about 1/2 ton per acre to over 2 tons per acre while neutral detergent fiber (NDF) content ranged from less than 19% to over 43%. These fiber levels encompassed the full range between quality classes of Supreme hay of about 33% NDF, to Fair or even lower at over 42% NDF. Protein and digestibility similarly declined over that period.  When estimated over a single year or multiple years, we can still see this yield-quality tradeoff (Figure 2). A 35-day cutting schedule resulted in over a 2 ton per acre advantage versus a 24-day schedule over three years and averaged across 18 varieties. However, much of the hay harvested over this three-year period was considered medium or low quality, while the early harvesting strategy resulted in much higher quality hay. In this area, cuttings typically ranged between five and eight cuts per year. Many growers resolve this issue by splitting the difference and choosing an intermediate yield and quality, hoping for adequate returns per acre while producing good quality for dairy production. Usually this results in harvest at late bud or early bloom periods, or by scheduling harvests at about 28-day intervals. This has the advantage of predictable schedules for planning purposes. However, is this the best strategy? A 28-day harvest often results in disappointing forage quality during high-temperature spring and summer periods while also compromising yields. In our study, the 28-day schedules also resulted in a significant number of harvests classified as non-dairy (Fair and Good) hay over the three-year period (Figure 2). The 24-day schedule improved quality significantly, but yields were quite a bit lower than either the 28-day or 35-day schedules. A third factor If that were not complicated enough, harvest schedules also have a profound effect on long-term stand persistence. Early harvests almost always result in stand losses, something that has been confirmed over years of field studies in many parts of the U.S. In the study cited previously (Figure 2), the 24-day harvest schedule resulted in the plant population of alfalfa varieties almost completely disappearing after only three years. For the 35-day schedule, all varieties still had excellent stands in year three and were capable of several more years of production. That makes a large difference economically, since a six-year stand carries lower costs than a three-year stand. So, how do we resolve this yield-quality-persistence trade-off issue? Go long It has been recommended for years by forage agronomists to “go long” at least once or twice per year to replenish root reserves, allow recovery from frequent cuttings and wheel traffic stress, and allow for subsequent healthy regrowth. Additionally, in irrigated regions, growers could make sure the crop is well-watered during that longer growth period to make up for water deficits that may have accumulated. Such a strategy means that growers would need to accept the lower quality that results from the extended days to harvest. This could be called the “staggered” harvest schedule, where an individual field would be alternatively harvested short and long over the season. This could be easily accomplished on farms that have many fields by alternating the sequence of fields. For example, on a farm with eight fields, instead of using a harvest order of A-B-C-D-E-F-G-H on first cut and second cut, a farm might harvest A-B-C-D-E-F-G-H followed by E-F-G-H-A-B-C-D on cut two, then back to A-B-C-D-E-F-G-H on the third cut. This is likely to naturally extend the harvest schedule on some fields while shortening it on others. The on-the-ground reality is that growers have a hard time keeping everything on schedule anyway since it takes some time to get across multiple fields. This staggered approach has the goal to produce a stream of high-quality and moderate-quality hay throughout the growing season. It’s been our observation that growers are unable to attain high quality on every cutting, even if that’s their intention. So, using this strategy, a grower could reliably produce some high-quality alfalfa along with some of medium quality. Put to the test Does this concept hold water? Recently, we completed two years of a harvest schedule study at the Kearney Research and Extension Center in Parlier, Calif. In this trial, we examined three schedules: normal (28 days), late (35 days), and staggered (35 days followed by 21 days). This resulted in about five cuts per year for the late schedule versus about seven to eight cuts per year for the normal and staggered plots. All crops were irrigated once per week to meet the full evapotranspiration (ET) requirement of the crop. We had eight varieties, including reduced-lignin types. If this concept works, it should work for both conventional and reduced-lignin varieties. The staggered schedule virtually guarantees some cuts to be high quality and some to be lower quality over the season.  Three- to four-cut systems We have found similar results in studies conducted by our late and dearly missed colleague Steve Orloff in the Intermountain Region of California. Delaying the second cutting in this shorter season environment nearly always resulted in superior returns. In an analysis of economic returns over a 10-year period, comparisons of three- versus four-cut systems (three-year dataset) indicated that yields nearly always were more important economically than quality. Strategies such as delaying second cutting in a three-cut system improved yields and economic returns. In the delayed second cutting treatment in the three-cut system, both forage quality and yields were improved. We have seen that 28-day schedules in hot summer periods often fail to produce dairy-quality hay sufficient to satisfy nutritionists, and also reduce yields. So, why not “go long” to improve yields during those cuts and replenish root reserves? Economic returns are a major consideration since both yield and quality impact gross returns. In our studies, yields were still the most important economic factor. Balancing this yield-quality-persistence challenge as related to harvest schedules is not easily resolved, and most growers choose a middle path, which often compromises yield and quality as well as persistence. However, this may not be the best solution, since sometimes longer or shorter schedules may be superior to a regular harvest schedule. A “staggered” approach, which allows some individual cuts to “go long” for improved yields and replenished root reserves for stand longevity, is suggested. This may require a little higher management level but provides a steady stream of both high- and medium-quality hay products over the season. Acknowledgements: Many thanks to Brenda Perez and Steve Orloff for their contributions to these datasets. This article appeared in the November 2021 issue of Hay & Forage Grower on pages 10 and 11. Not a subscriber? Click to get the print magazine. |