Crimes of the cornfield |

| By Paul Dyk |

|

|

|

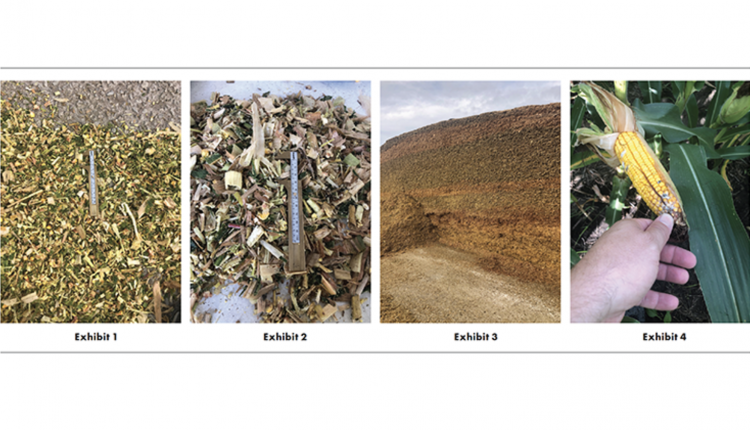

The author is a dairy nutrition consultant with GPS Dairy Consulting LLC and is based in Malone, Wis. In a corn silage system, producers are served by two equally important groups: the nutritionists, who help feed the silage, and the agronomists, who help grow it. With apologies to viewers of the “Law & Order” television show, these are their stories. While no murder has occurred in the making of your corn silage, crimes do happen. It is only through the cooperation of the nutritionist and agronomist that future issues can be avoided. Dissect the crime scene The body in the case of the corn silage caper usually comes in the form of depressed milk production or unhealthy cows. Cows were milking well, and now as they go into new corn silage, the milk production has dropped. Perhaps manure is uneven, a few cows are sick, or maybe reproduction measures are turning south. The crime scene almost always begins at the silo where the corn silage resides. A visual observation might seem simplistic, but it’s a good starting point. After safely collecting a representative sample, look closely and use a measuring device to assess cut length.  In Exhibit 1, we can see some corn silage that was chopped finely, close to 10 millimeters (mm) and shorter than we would like to see it. This silage is unlikely to develop an acceptable rumen mat in a high corn silage diet. In this same picture, you can see a few whole kernels. A short cut with whole kernels equates to a double homicide. Exhibit 2 shows some corn silage that is unevenly cut. A few measurements picked up quite a few pieces over 25 mm. Two adjustments should have been made on this chopper — get the cut length between 20 and 25 mm and check the shear bar. If the shear bar is wearing, you will often see ragged or long pieces in the corn silage; these pieces create an uneven, sortable totally mixed ration (TMR) in some situations. Exhibit 3 is a great visualization of variation in the bunk. While color is not always an indicator of silage quality, differences in color across the bunker silo face likely indicate various hybrids, fields, and dry matter concentrations. A single lab sample doesn’t always reflect the range in bunker silo variation. Processing corn silage has received considerable attention, but problems still occur in the field. Worn processors, dry corn, or custom choppers that are in a hurry can all lead to less-than-ideal processing. On-farm processing scores, the SilageSnap app, and lab analyses can quantify processing effectiveness. All good ideas, of course, but a quick visual usually points you in the right direction. Perhaps just as important as the harvest measurements for corn silage is the storage. At times, the crime scene is easy. Like a bloody knife in the hands of the alleged perpetrator, mold at the edges or top of the pile or bunker is an easy sign that something is amiss. Was an oxygen barrier film used? Were the sides of the bunker wrapped? Did you run out of tires to cover the pile? There can be times that a visual doesn’t tell the whole story, and we need to go to forensic-level analysis. Thermal imaging can reveal hot spots in the bunker — perhaps removal rate is insufficient, inoculant use was incomplete, or packing was inadequate. As you walk away from the crime scene, you likely already have enough evidence to point to the perpetrator (or process), but we often must dig deeper. Examine lab evidence The crime lab, or in this case, the forage lab, is usually the next stop in discovery. Target desired tests toward the crime. If poor fermentation is suspected, spend the money for wet lab analysis that offer levels of fermentation byproducts. If mold issues are a concern, spend the money for mold and mycotoxin identification. Starch, fiber, and protein are starting points for a rookie detective. Fiber digestibility is a key metric that nutritionists like to dissect. Highly digestible brown midrib (BMR) hybrids can offer 67% neutral detergent fiber digestibility at 30 hours (NDFD30) while older, traditional grain hybrids might be closer to 55% NDFD30. But it’s too simplistic to just think that hybrids perform equally across geographies and soil types. A lot of dairies are on the fringes of great corn ground, and they thank their ancestors every spring for settling on extremely heavy or light soil, in a floodplain, or on the side of a hill. Focusing on a healthy plant — think irrigation, fungicide, and soil health — can lead to corn silage with a NDFD30 in the range of 60% to 62%. You might have to dig deeper than one 30-hour fiber digestibility metric. Looking at 12-hour digestibility might also be helpful. High-producing cows have a high turnover rate in their rumens and require a lot of digestion up front. Don’t forget the undigestible fiber (uNDF240). High levels are essentially a filler in the diet and can limit intake. Measurements like acid levels (acetic, lactic, and butyric) and pH can often help us understand problems with fermentation. Beyond lab analyses for mycotoxins, have a discussion with the agronomist. What did they see in the field? Exhibit 4 was taken in 2021. Can we anticipate a problem here? Prevent the next crime With the evidence in hand, there are two things left to do. First, if possible, adjust for the corn silage on hand. Dispose of moldy corn silage, adjust rations for starch digestibility, and maybe add straw to counter particle length or add a binder to account for mycotoxins. Second, prevent the crime from happening again. This usually starts in the year before corn silage is planted. Hybrid selection, purchasing and committing to fungicides, and buying a quality inoculant are often decisions that need to be made three to six months before the seed is placed in the soil. If processing and storage were the culprits, plan a harvest meeting with your chopper operator. Is the chopper maintained, are there enough tires to fully cover the pile, or does another pack tractor need to be added? Explain the issue and work toward a solution — but perhaps omit the crime scene analogies. This article appeared in the January 2022 issue of Hay & Forage Grower on pages 12 & 13. Not a subscriber? Click to get the print magazine. |