Hay stocks drop 7%; hold on for a wild ride |

| By Mike Rankin, Managing Editor |

|

|

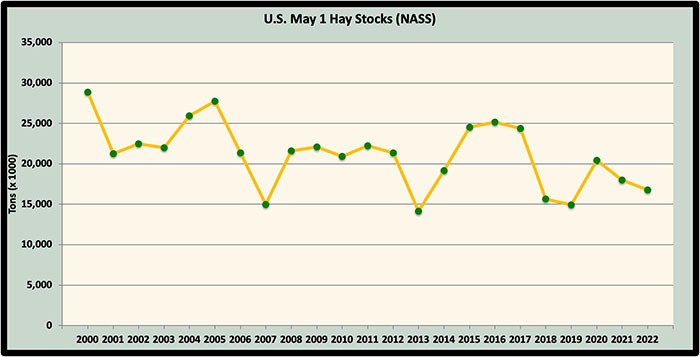

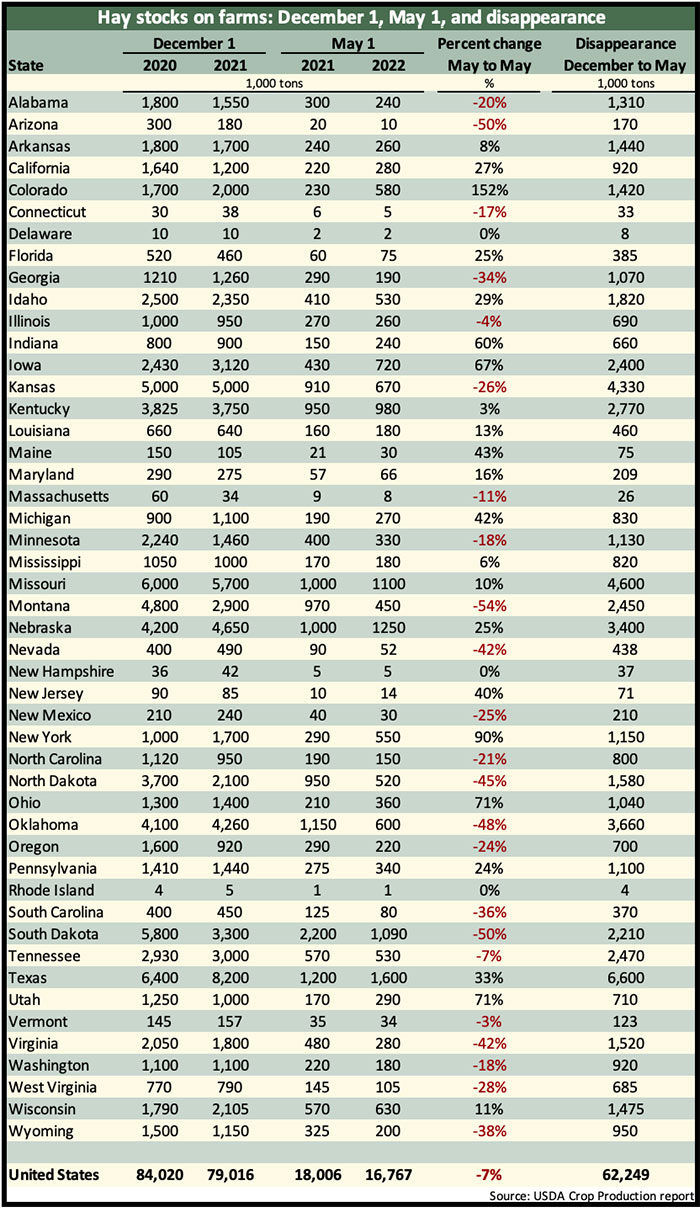

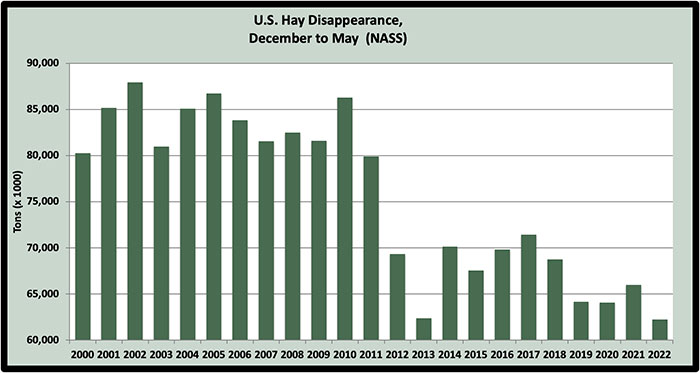

The amount of hay in the U.S. haymow continues to shrink and is down another 7% from a year ago. Compared to May 1, 2020, the inventory is down 18% or 3.7 million tons. Based on USDA’s Crop Production report released last week, May 1 hay stocks dropped by 1.2 million tons from a year ago. This follows a 12% decline in May stocks from 2020 to 2021. Hay stocks currently stand at just over 16.7 million tons. This past December, year-over-year hay stocks declined by about 5 million tons. At 16.7 million tons, May 1 hay stocks are still slightly above 2018 and 2019 inventories but are far below 2015 to 2017.  Some of our largest hay-producing states, especially in the West and Northern Plains, had significant year-over-year May 1 stock declines (see table below). States with some of the largest declines include: Montana: down 54% South Dakota: down 50% Arizona: down 50% Oklahoma: down 48% North Dakota: down 45% Nevada: down 42% Virginia: down 42% Conversely, there were also some major hay-producing states with significant inventory gains. This group included: Colorado: up 152% New York: up 90% Ohio: up 71% Utah: up 71% Iowa: up 67% Indiana: up 60%  Hay disappearance Hay disappearance (primarily feeding) between December 1, 2021, and May 1, 2022, totaled just over 62.2 million tons. This was about 4 million tons lower than the previous year and set a record low hay disappearance (see graph). Previously, the lowest hay disappearance occurred between December 2012 and May 2013, totaling 64.4 million tons.  A new normal has developed in terms of hay that moves out of the barn from December to May. Prior to the 2012 drought year, disappearance from hay barns and stacks was always in the 80 to 85 million tons range. Since 2012, it’s been rare to have a year where disappearance exceeded 70 million tons. During three of the past four years, hay feeding has been under 65 million tons. A look ahead The current hay stock numbers are just one of many reasons for historically strong prices moving through 2022. Already, hay prices are $80 to $150 dollars per ton higher than they were a year ago. How much higher prices can go before buyers reach their limit remains to be seen. Drought conditions continue to haunt many U.S. regions, especially the West. This situation could improve or get worse and will ultimately have a big impact on the direction of hay prices and its availability. Continued record-high commodity prices also provide reason for stronger hay prices in 2022. Many livestock feeders will look to good-quality hay to replace energy and protein previously supplied by corn and soybeans. Milk prices have improved significantly in 2022, but a chunk of that income will be offset by higher feed prices. All hay crop input prices have gone up substantially. Other factors aside, hay growers will expect to receive more for their hay just based on price hikes for fertilizer, fuel, machine parts, and chemicals. Export volumes during the first quarter of the year have been slightly better than 2021. This always helps set the tone for prices in the West. It’s reasonable to expect that 2022 hay prices will reach an all-time high and stay that way for a significant stretch of months. There are virtually no indicators that point to weaker prices, although a strong hay production year might temper the upside. Finally, let’s not forget the two hay market mantras that hold true every year. First, high-quality hay always sells for a premium price and costs no more to make than poor-quality hay. Second, hay markets are largely a regional phenomenon. Local weather conditions and predominant enterprise types (dairy, beef, or equine) will ultimately dictate the demand and price of hay. Even so, no region is likely to see lower prices in 2022 than what was paid in 2021.

|