Nitrogen needs differ in fall stockpile |

| By Alan Franzluebbers |

|

|

|

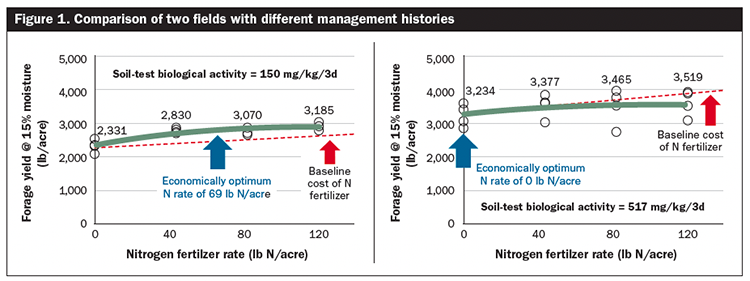

The author is a soil scientist with the USDA Agricultural Research Service in Raleigh, N.C.  Stockpiled tall fescue in early November with variable nitrogen fertilizer application to assess growth and quality in central North Carolina. Alan Franzluebbers We've reached the time of crisp fall mornings, and the grass is green all around — well, as long as it’s been raining in your neck of the woods! Throughout much of the eastern U.S., cool-season forages are back to life, and you might be offering succulent grass for the herd. But what about your winter forage needs? Winter grazing requires deferment in the fall so that cool-season forages can be stockpiled. Fresh, grazed forage is often more cost-effective than feeding hay throughout the long winter. Stockpiling for winter grazing is easy on the pocketbook but requires some planning. Preparing for winter grazing means evaluating the condition of pastures at the end of summer. Is tall fescue a major component of your pasture? Have summer annual species overtaken the pasture? Has the pasture been adequately fertilized and limed in the past? Answers to these questions might determine whether the pasture is a good candidate for fall stockpiling. You’ll know if tall fescue will be present in the fall even if it was not visible at the end of the summer. Just think back to last fall or spring. Tall fescue can go dormant in the summer with the heat and extended dryness. If the pasture is overgrown with crabgrass or other smothering forages, then a late summer clipping will help expose the young tall fescue shoots to the sun and help them get a good start. Many agricultural advisers will tell you that you need to fertilize the pasture with 40 to 100 units of nitrogen per acre to stimulate growth in the early fall. However, if there is insufficient moisture during a dry fall, that nitrogen may be wasted because conditions aren’t conducive for growth. Another reason why nitrogen might be wasted is because the soil may be providing enough nitrogen for abundant fall growth from the decomposition of organic matter. Small organisms, big benefits Decomposition occurs daily but gets rejuvenated following the hot and dry summer when bright sunshine still heats the ground and precipitation becomes more frequent to energize the microorganisms living in soil. Those soil bacteria and fungi get to work consuming the roots, plant residues, and feces that were deposited in and on soil. They release the carbon fixed in plants back to the atmosphere as carbon dioxide to complete a natural cycling. In the process of decomposing these organic carbon compounds, soil microorganisms also release mineral nitrogen contained in these protein-rich plant materials. Mineral nitrogen is composed of ammonium and nitrate — the very elements that forages need to make abundant growth when there is sufficient moisture and a suitable temperature. How would you know if there’s sufficient nitrogen to satisfy plant growth requirements? Well, you could get a soil test. If you need 100 units of nitrogen, and a soil test indicates only 10 units are available at the time of sampling, then you might logically think you need to apply 90 units of nitrogen fertilizer. But this is only a part of the story. If you asked for a soil test to determine the total amount of nitrogen, including both inorganic (mineral) and organic nitrogen, then you might be surprised if you get the report with 1,000 units of total nitrogen present per acre. Fortunately for us, not all of the organic nitrogen is available to plants in our lifetime, so that we can savor this ecosystem reserve of nitrogen for longer. But your most important question to ask might be: “How much nitrogen will be available during the fall stockpile period?” A better way Soil testing labs would have to incubate a soil sample for several weeks to determine the actual amount of mineral nitrogen released by those microorganisms consuming organic matter in soil. This process is called nitrogen mineralization, or the conversion of organic nitrogen into mineral nitrogen (ammonium and nitrate). Fortunately, we’ve discovered a quick method to estimate the amount of nitrogen mineralized from soil. This is from the flush of carbon dioxide released during a three-day period following rewetting of a dried soil. The burst of soil microbial activity following rewetting of dried soil, also known as soil-test biological activity, gives a fairly accurate snapshot of the long-term rate of soil microbial activity. Soil microbial activity is strongly associated with nitrogen mineralization potential. Different soil types can have different inherent nitrogen mineralization potential, but importantly, historical management can also greatly influence the nitrogen mineralization potential of a soil (see graphs).  Crude protein in fall stockpile is often more than adequate for pregnant beef cows in winter. Soil microorganisms are providing a service to you and your cattle herd by recycling nitrogen in the pasture back to this stockpiled forage. Are you ready to appreciate and take advantage of this process? For information on how soil-test biological activity can influence the amount of nitrogen needed to optimize economic return of fall-stockpiled tall fescue, refer to bit.ly/HFG-Nrate. This article appeared in the November 2022 issue of Hay & Forage Grower on pages 18-19. Not a subscriber? Click to get the print magazine. |