The art of the tarp |

| By Mike Rankin, Managing Editor |

|

|

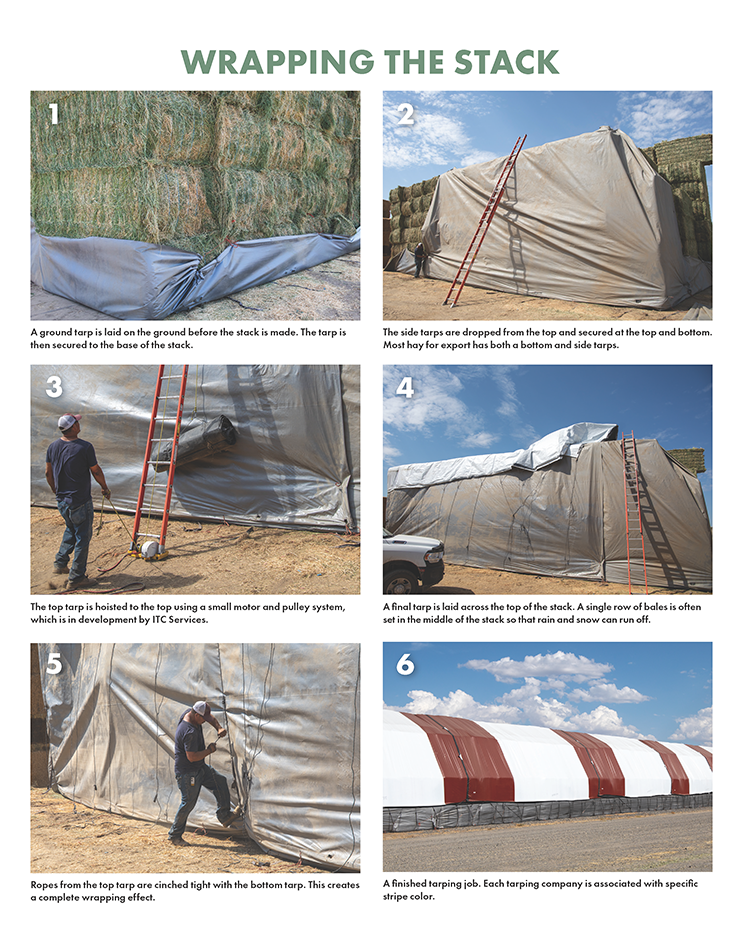

Tarping hay following harvest is the primary storage method for growers in the arid West. Although some growers purchase their own tarps, it’s far more common that they use the services of a tarping company. Among the many unique rural landscape features found in the western United States, first-time visitors will witness thousands of scattered haystacks that have seemingly sprung forth from the parched soil like the even more predominate sagebrush. Stacks of hay can be seen along the road, in the distance, on hilltops, and in manicured farmstead gravel lots. Adding to the Western skyline are the colorfully striped tarps that top the vast majority of these haystacks. One of the companies responsible for painting the tarp-laden landscape is ITC Services, based in Moses Lake, Wash. The area is part of the Columbia Basin, which is rich in irrigated crops and a stronghold for alfalfa and timothy production. This land base receives about 7 inches of rain per year, most of which comes in the winter.  Freddie Prado oversees multiple field managers and tarping crews from the corporate office in Moses Lake, Wash. He’s worked at ITC Services for over 20 years. “Eighty-five percent of our business involves leasing tarps to farmers,” Prado said. “A grower calls, tells us where the stack is located, and we go cover it. Whenever hay from the stack is used or sold, we then go pick up the tarps. When time allows, and if stacks are only partially emptied, we will go to the farm, fold the tarp back, and then reclose the stack.” According to Prado, a tarp can last for years, or it can be destroyed in 45 minutes of severe wind if it’s not properly secured from the time of installation until the stack is gone. Part of the tarp lease agreement entails that an ITC crew will inspect the tarp and tighten it down as needed. Job 1: Make dry hay Prado oversees several million tons of hay being covered in Washington each year. A successful tarping outcome begins with putting up dry hay. “If bales are a little wetter than desired, it’s best not to wrap the stack right away,” Prado said. “We’ve had situations where it was going to rain, and we’d cover the stack and then take the cover off after the rain passed to allow the bales to dissipate moisture.” It’s also important that growers know where the hay is ultimately going. Hay destined to be exported needs to be fully wrapped, which includes a ground tarp, side tarps, and a top cover. Many buyers in the export or horse market don’t want bleached hay, so tarping is essential if the entire stack is going to be sold to these end users. For hay being used locally by dairies or feedlots, hay producers sometimes choose to only use a top tarp or top and side coverings. Regardless of use, Prado emphasized the importance of putting stacks in a well-drained area where water won’t accumulate during the winter. In some areas, enough room must be left between stacks to allow for winter snow removal. The stack location also needs to be accessible for trucks and loading equipment. Most haystacks are the width of either two or three 8-foot-long bales (16 or 24 feet), although some regions such as Montana, for example, favor a one-bale width. The height is often determined by the stack wagon that picks up bales out of the field and delivers them to the stack. Prado prefers growers also put a single row of bales lengthwise across the top of the stack, forming an inverted “V” or ridgeline, so that water and snow can run off the top. The tarps are manufactured to fit bale stacks that are one to five bales wide, and the length of the tarp can’t be too long so that they can be handled during installation. Insurance companies often limit how much hay can be put in a single stack, which will dictate length and the amount of separation between stacks. The prevailing wind impacts the direction the tarp is installed, with overlap openings facing in the opposite direction of the wind. This allows the wind to blow over the overlap and not into it. Most overlaps are 4 to 6 feet. Of particular interest is that each tarping company has their own unique top tarp stripe color. ITC Services’ tarps are recognized with a maroon stripe. A need to communicate If hay is targeted for export, farmers need to call their tarp company before a field is baled so that the ground tarp can be put down. “We prefer farmers call us when they start raking,” Prado said. “We’d love a couple days’ notice, but that doesn’t always happen. Often, our field managers stay in close contact with our customers and know about when they will be cutting.”  Tarping crews work throughout Washington on any given day. Trucks are equipped with GPS units that help track their location using specialized software. During the course of the summer, the requests for tarping ebbs and flows. In between cuttings, the workload slows down, while during harvest it becomes extremely busy. A tarping crew generally consists of four people, although another person or two may be needed in windy conditions. Prado said that they’ve been fortunate to maintain enough labor to service their customers, although, like every business, labor costs are rising. “It’s a tough, physical job to tarp hay, but you’d be amazed how fast a good tarping crew can get a stack covered,” he added. All of the ITC crew trucks are equipped with GPS units. Using specialized software, Prado and his field managers are able to identify the location and movement of all their tarping crews at any given time. The tarping advantage “Although the benefits of covering hay destined for export are obvious, more and more of the dairies and feedlots are recognizing the importance of hay coverings,” Prado said. “They get a higher quality product, and the bottom bales aren’t contaminated with soil and stay dry. From a marketing perspective, growers who cover their hay are generally going to sell their hay faster than those that don’t, and they will get a better price.” Prado explained that the advantage of a tarped stack to growers is that they’re flexible in where hay can be stored. Tarping helps to eliminate hauling hay long distances with stack wagons to a central barn location. Even so, it’s probably more economical to have barns if an entity like an exporter has a single storage location where hay is being moved in and out of the same place year after year. The cost for tarping a haystack is charged either by the ton or linear foot. That cost will vary depending on the completeness of the tarping job. Only tarping the top costs less than a complete wrap (bottom, sides, and top). The bale and hay type are also factors, as high-value three-string bale stacks for export or retail are often covered on the ends as well. Prado noted that it’s common for a large hay producer to work with more than one hay tarping company. As for his biggest challenge, Prado cited the same answer that farmers often give — the weather. “It’s not just dealing with rain at an inopportune time, but also sometimes having to work in extreme heat.” As long as hay gets made, the tarping industry should continue to thrive. Getting hay covered in a timely and effective manner is a logistical dance between grower and business. In most cases, it’s a mutually beneficial relationship, and it’s that relationship that will continue to leave its mark on the Western rural skyline for years to come. From farmer to tarping entrepreneur  Glen Knopp By 1990, Knopp was working full time selling tarps and covering stacks. He moved the business to Moses Lake in 1998. His Canadian tarp supplier wasn’t as responsive as Knopp would have liked in terms of shipping product, so he started making his own tarps with the help of various U.S. suppliers. Knopp also developed a system to help keep the tarps intact during periods of high winds. Eventually, he found a manufacturer that was willing to integrate improvements that Knopp wanted to make to the tarp fabric. These days, ITC tarps are being manufactured in both the U.S. and abroad. Through the years, Knopp grew not only his hay tarping business, which now provides rental and covering services in 13 states and sales in all 50 states, but also several other companies that provide specialized tarps and liners for industries outside of agriculture. Approaching retirement, Knopp sold his companies to an Employee Stock Ownership Plan (ESOP) trust in 2020. Now, a third-party trustee ensures that the business is managed in the best interest of the employees. After working a designated amount of time for the company, each employee gets annually issued stock shares that grow in value as the company does. Essentially, all of the employees become shareholders and owners of the company. “I wrestled with this decision for a long time,” Knopp said. “This option allows the company to move forward with the same management team, vendors, and business model that we’ve always had. The transition was seamless, and our customers couldn’t even tell there was a change.” These days, Knopp still serves as the chief visionary officer and board chairman for the family of companies, but most of his time is spent on other noble pursuits. He and his wife, Carol, travel and visit their eight children, who are scattered across the country. Knopp is also completing his college bachelor’s degree and has finished the required classes to become an ordained minister. Finally, he and Carol have started a nonprofit organization called Minister to the Nations. In closing, Knopp said, “I guess I want to spend the rest of my life trying to advance God’s kingdom here on earth.” There’s little doubt that he’ll have the job covered.  This article appeared in the November 2022 issue of Hay & Forage Grower on pages 26-29. Not a subscriber? Click to get the print magazine. |