It’s the grazing bad times that can break you |

| By Mike Rankin, Managing Editor |

|

|

|

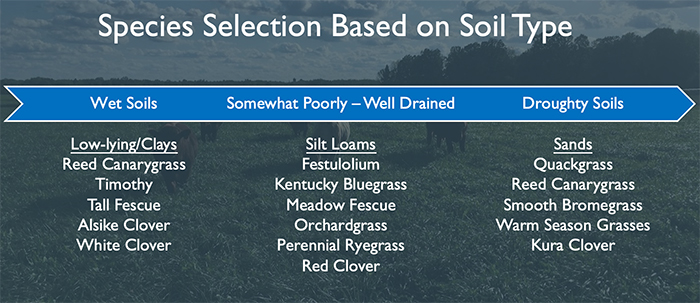

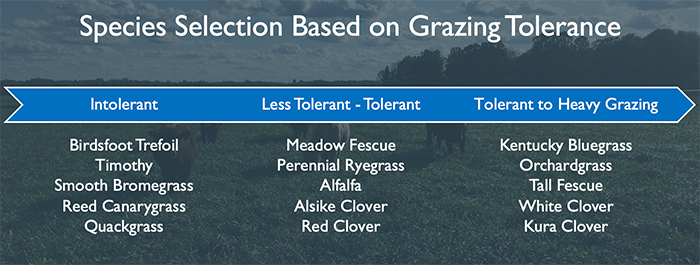

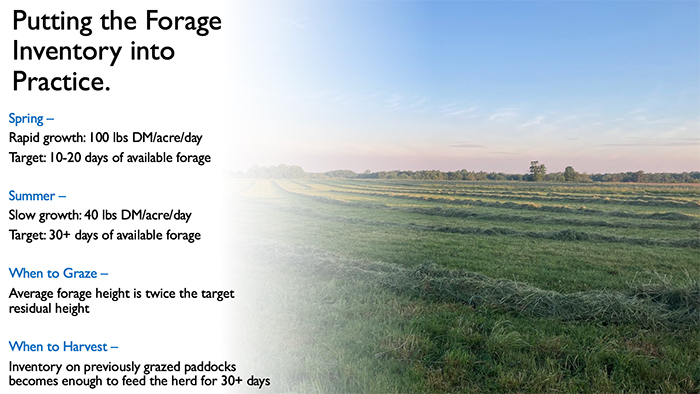

Grazing livestock is often depicted as animals out on lush, green pastures, moving periodically to new paddocks with even more lush, green forage. Although this is true, there is also the reality of mud in the spring and not enough forage in the fall. It’s these two time slots that Jason Cavadini refers to as the shoulder seasons.  Jason Cavadini “It’s these shoulder seasons, along with the summer slump, that tend to make or break an operation,” said the grazing outreach specialist with the University of Wisconsin Division of Extension. Cavadini expounded upon some of the problems and potential solutions for navigating the shoulders of the grazing season at the GrassWorks Conference held earlier this month in Wisconsin Dells, Wis. “The shoulder seasons can significantly add to the stress of a grazier,” Cavadini said. “This stress becomes amplified with more extreme weather events during these times of the year.” The grazing specialist gets a lot of questions during the shoulder seasons from farmers looking for a response to their problem. He noted that sometimes a response is necessary, but almost always, it is costly. In many other instances, the situation needing a response was avoidable. “Instead of banking on a solution during the heat of the problem, let’s plan for a resilient system, and that starts with preparation,” Cavadini asserted. “Set goals that will drive every decision, keep your goals in mind when responding to an adverse situation, and don’t be too quick to abandon your goals.” Some of the common goals in a managed grazing system are to maintain a diverse sward, strive for a consistent and dependable yield with high forage quality, cause minimal land impacts, maintain good animal performance, minimize off-farm inputs and expenses, and maximize the length of the grazing season. “Without the three principles of managed grazing — rotation, rest, and residual — we’re going to be responding to an adverse situation rather than be prepared for one,” Cavadini said. “Another factor is stocking rate, which really got exposed last year, and it’s something that many people don’t put enough thought into.” Look for ways to improve Grazing operations that are resilient generally get that way by continually learning from adversity such as a drought, excessive moisture and mud, or a dramatic cool-season grass forage slump. Once these extreme conditions come and go, Cavadini said that it’s important to look back and ask yourself what could have been done to soften the blow or avoid the problem altogether. “One of the common mistakes I see made is with species selection,” Cavadini noted. “Know what species will work on your farm’s soils. Select proven species and varieties rather than the newest ‘hot’ thing on the market. Sometimes the best approach is simply to learn to manage what you already have.”   The grazing specialist also said to consider if species complement each other. “The classic example of this is seeding orchardgrass with meadow fescue,” Cavadini said. “Cattle will devour the meadow fescue and leave the orchardgrass. In a few years, the meadow fescue will be gone, and you’ll have nothing but orchardgrass, so don’t mix the two.” In addition to species selection, take time and determine your forage inventory. “You have to know how much forage is available on your farm,” Cavadini said.  Walking right alongside your forage inventory efforts are carrying capacity and stocking rate. “Your stocking rate needs to match your management and your carrying capacity,” the grazing specialist asserted. “Last summer, a lot of people in Wisconsin found that they didn’t match. What you graze and how often you move animals will have a large impact on your farm’s carrying capacity.” Next week: Cavadini’s thoughts on dealing with a summer slump or drought. |