Making the Grade |

| By Haley Ruffner |

|

|

|

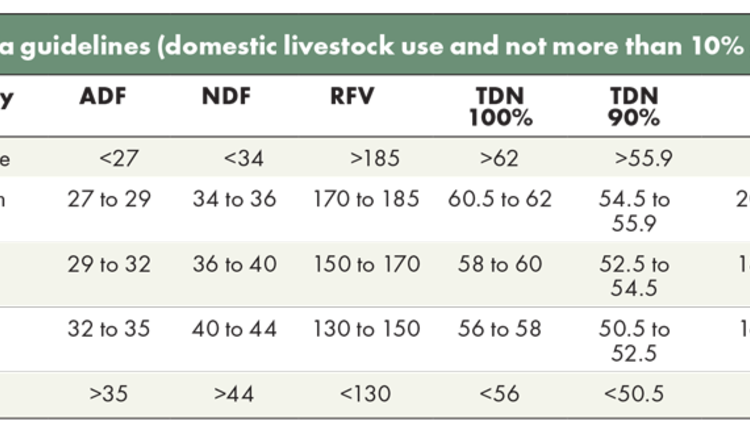

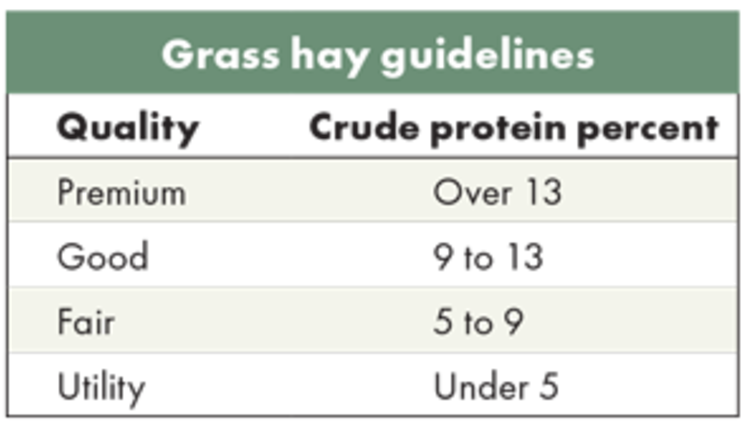

The author is a hay broker with Aden Brook, a nationwide supplier of hay. Ruffner specializes in the horse hay market and is based in Alamosa, Colo.  Although the USDA has Hay Quality Designation Guidelines (see tables) based on nutrition tests for alfalfa, that alone does not cover all of the terms and grades we use to describe hay. Many of the terms we use are subjective since not everyone follows the USDA chart, or if they do, it may not be comprehensive enough to fully determine quality. For example, “premium” hay means something different to a dairyman in Texas than it does to a feed store manager in Florida. A customer asking for “good” hay may be referring to hay with a relative feed value (RFV) of 160, or they may be simply asking for mold-free hay that is safe to feed their animals. Asking questions to determine what kind of animals they have, if they have specific nutritional requirements, and what their quality expectations are will provide better insight and let them describe in their own words the grade of hay they are looking for. Brokers dealing with more than one type of customer should be able to describe hay in concrete, specific terms in addition to those the USDA provides. Priorities vary For dairy and feedlot customers who are mixing a ration, a forage nutrient test may be the deciding factor in determining value of a hay lot. If hay is ground or put through a total mixed ration (TMR) mixer, secondary characteristics like bleaching, stack damage, small amounts of mold, and stem size are largely irrelevant. While these factors still impact the overall quality of hay and are necessary information for customers to have, they may not carry as much weight for dairy and feedlot customers who are buying primarily based on a test. Feed store and horse customers, on the other hand, may not consider a forage nutrient test at all when purchasing hay. Unless they are feeding horses with specific dietary requirements or metabolic issues, they are more concerned with the overall aesthetics of the hay and want good color, smell, and palatability more so than a specific nutritional profile. Although these customers may not ask for a test, it still provides necessary information for a broker to have in being able to accurately grade hay. Coastal bermudagrass hay, for example, can be high in neutral detergent fiber (NDF), causing it to be indigestible to horses and lead to colic.  Alfalfa that tests high in protein and RFV may be too rich for horses accustomed to lower testing hay and can also cause health issues if they are not transitioned slowly. Part of the value a hay broker provides to customers is the ability to educate and anticipate problems before they arise, so being able to decipher a forage test analysis and accurately share what that means for a customer’s animals is integral. Storage impacts quality Hay sellers must consider storage when grading hay as it will impact the quality over the weeks and months after baling. Hay stored outside with no tarps will begin degrading almost immediately, being impacted by sun bleaching, rain or snow, and shrink from wind and exposure to elements. Hay that is graded as “supreme” quality in the field upon baling but not stored correctly will not retain that same grade for long, even if it takes one rain shower before being tarped. The resulting bleached color and moisture will impact the price and caliber of customer it can be delivered to.  If farmers are unwilling or unable to store hay and prefer to sell out of the field, their options become limited to more local shipments due to the dangers of shipping uncured hay. Shipping out of the field is not an effective way to bypass setting up storage because new hay needs adequate space and airflow to allow it to heat and cure. Fresh hay loaded on a dry van and shipped across the country is liable to heat and mildew, arriving to the customer with significant damage. Likewise, fresh hay that survives shipping but is packed into a customer’s barn upon delivery also poses a risk of fire if all parties are not diligent about monitoring moisture levels. Considerations of storage are almost as important as looking at the quality of the hay itself upon baling, especially for customers using large quantities of hay over longer stretches of time. A stack of hay that will ship over the course of several months, especially if it’s stored outside in a region that gets significant precipitation, will degrade substantially over time. Look, touch, and smell Our senses can help us grade hay — the color, smell, texture, and other visible and tactile qualities play a part in determining its quality. Horse customers, in particular, are usually much more concerned with the look of the hay over its nutrient analysis. Does the hay smell musty or fresh? Is it bright green, or has it been sun bleached? Does it feel coarse to the touch, or is it soft and leafy? Taking a close look at the hay for different grasses and legumes will give a clear idea of its contents in terms of how “pure” it is or the mix of plants it contains. A visual examination to look for weeds, rocks, or trash that may have been baled up is important in being able to accurately describe the hay’s quality to potential customers. Hay that tests well, is barn stored, has good color and softness, but contains foxtail on visual examination must be graded as such and disqualified for sale as horse hay. Although a nutrient test used in conjunction with physically looking at the hay offers a more well-rounded picture of its true grade, we can get a lot of information from a stack’s sensory qualities. Visual analysis of a haystack can be effective in validating nutrient test results or giving a preliminary idea as to what the test’s results may be before the lab sends them back. For example, alfalfa with good color and excellent leaf retention that doesn’t shatter when pulling a handful of hay from the bale will likely test higher than alfalfa that appears bleached and falls to dust and stems when opened. Grass hay that appears stemmy and is more mature will be less palatable and lower in nutrients for horses than softer, finer-stemmed hay that was cut earlier. Consistency also pays Consistency within a batch of hay is largely a matter of attention to detail by the farmer across all stages of the growing, cutting, and storage processes. How clean do the fields look before they are cut? Are there weeds or trash visible, or does the hay appear to be uniform? How old are the stands of hay, and does the farmer sort or grade old stands separately from newer stands? Hay that is consistent prior to being cut must also be baled in similar conditions, either by way of using a steamer to imitate ideal dew conditions or through careful timing by the farmer putting the hay up. Is it one farmer putting up hundreds of acres alone, or is there a crew that comes in to make sure fields are all baled at the optimum moisture level? Conditions can vary drastically even in fields that are close together, so talking to farmers about their baling practices will give insight into the level of consistency to expect in the finished product. Consistency in storage will also determine the hay’s grade over a period of time. If one stack of hay is stored in a barn with no sides and another stack is in a fully enclosed barn, the outside bales in the open barn will degrade much more than those in the four-sided barn. A batch of hay that tested within the USDA-described “premium” range upon baling but was stored with some stacks tarped and some untarped will no longer be the same quality by the following spring, especially if it comes from a region that gets significant rain or snow over the winter. The untarped stacks will have experienced enough stack damage that at least the top bales will have to be sold as a different grade of hay. While not all customers are overly concerned with the minute details of hay across a large batch as long as variations fall within one grade (for example, a certain range of RFV), some will expect to know if stem size will be slightly larger from one load to the next. Even for less particular cattle or feedlot customers, consistency in bale weights is key to ensure that the value is the same across a series of loads. If there is variation in a product, being able to set that expectation with customers and building allowance for it into pricing will go a long way in providing accurate grading and quality assurance to customers. Having the conversation about growing, baling, and storage practices with farmers will give a clear picture on the level of attention to detail and consistency to expect across a batch of hay. Different types of customers will have different priorities in grading hay, so the ability to accurately describe a lot of hay in terms of its nutrient analysis, storage, physical qualities, and level of consistency will mitigate potential misunderstandings. Developing a clear line of communication with a customer in order to understand what their needs are is just as important as grading the hay itself. Matching a batch of hay to the right customer is equally a measure of having a clear picture of what a customer is asking for and being able to accurately evaluate and describe the product. This article appeared in the July XL 2024 issue of Hay & Forage Grower on pages 12-13. Not a subscriber? Click to get the print magazine. |