New forage grass maturity index introduced |

| By Mike Rankin, Senior Editor |

|

|

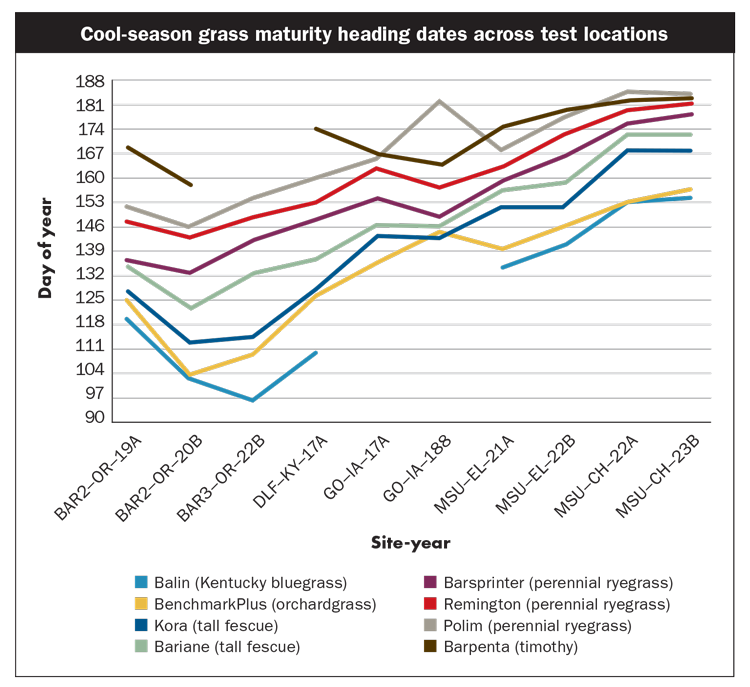

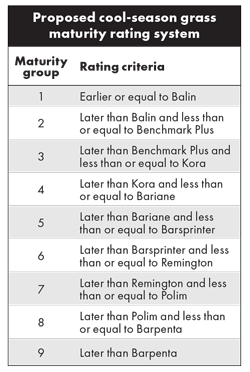

Will it head early? Will it head late? These two questions follow grass varieties around like a lost puppy. They get asked by grass breeders during development; they get asked by marketing departments; and most importantly, they get asked by farmers when they’re in the market to buy grass seed. Up until this point, assessing relative grass heading dates across the industry has been akin to the wild, wild West. Sure, individual companies have their own rating systems within the varieties they market, but there is not often consistency from one company to another. In 2016, a Forage Grass Maturity Working Group was formed to address the issue and develop a uniform system for measuring grass variety maturity. The working group consisted of both university and private seed industry representatives. At last January’s American Forage and Grassland Council’s Annual Meeting, Michigan State University’s Kim Cassida and the University of Kentucky’s Ray Smith reported on the group’s efforts to develop an accepted uniform protocol for accurately assessing the maturity of any cool-season grass variety, regardless of species or environment. “The grass segment is a little behind in developing a uniform industry rating system for describing and comparing the heading date of forage grasses,” Cassida said. “This contrasts with well-defined and objective maturity rating systems for other major crops such as fall dormancy rating for alfalfa, relative maturity rating for corn, and maturity group rating for soybeans.” The forage specialist also noted the high risk level associated with making a poorly informed variety choice. “It makes producers reluctant to invest in improving their grasslands through better plant genetics,” she said. “Lack of an industry standard for maturity also makes it difficult for grass breeders to accomplish meaningful progress in developing varieties with reliable heading dates relative to others on the market.”  More species made sense Cassida said that members of the working group hypothesized it would be better to include multiple species in the maturity rating development because that would allow comparisons across a wider range of variety maturities than might be possible within a single species. It makes the comparisons more robust. “We wanted to determine whether cool-season grass variety heading dates rank in a consistent order across diverse locations and multiple years and identify a subset of consistently ranked varieties to be used as reference standards for a maturity ranking index,” Cassida said of the group’s objectives. Grass varieties were tested across six locations from Kentucky to Oregon. Test plots were grown from 2017 to 2023, and 70 grass varieties were selected to represent a range of potential heading dates. The species included were tall fescue, orchardgrass, timothy, bromegrass, perennial ryegrass, annual ryegrass, hybrid ryegrass, and Kentucky bluegrass. Heading dates were recorded in the first cycle of growth during the first and second years following establishment. The heading date for each individual plant was recorded as the day of the year when at least three plant heads were completely emerged from the flag leaf collar of the plant. After all the varieties were headed, the plots were periodically mowed to a 4-inch height.  “Our goal to select reference varieties was done by identifying the ones that had the same relative maturity date ranking across years and environments,” Cassida explained. “Over all of the site-years, we ended up with a heading date range of 58 days from earliest to latest.” Of the 16 site-years completed, 10 met the group’s strict criteria for a complete and representative test. From the reams of data generated, the group identified eight grass varieties with observed heading dates that ranked similarly across each of the site-years (see graph). Cassida noted that the reference varieties in the middle of heading range were more consistent in relative rank across environments, but relative rank drifted slightly at the early and late ends of the range. A proposed protocol Kentucky’s Smith suggested that the final testing protocol brought forward would look similar to the way the exploratory research was done. Grasses to be tested, including the eight reference varieties, will initially be established in greenhouse pots, then transferred to the field in a spaced and replicated arrangement after approximately eight to 10 weeks. There will need to be a minimum of 15 plants per variety per replication. The year following a late summer or fall establishment, plots are checked three times per week after the grass variety begins to head. The heading dates are recorded as the day of the year (for example, February 1 is 32). The heading date is noted when there are at least three fully emerged heads per plant. Ratings are made over two growing seasons. “It is important to note that not all cool-season species have check varieties represented in the standard grass maturity test since many species-variety combinations did not show a consistent maturity ranking over locations and years,” Smith explained. “The check varieties have simply been selected to differentiate the range of relative maturities for cool-season grasses.” The single set of check varieties is used to designate the proposed grass maturity groups 1 to 9 (see table). Over the next five years, Smith said that the University of Kentucky, in collaboration with the working group, will ensure that viable seed is maintained of each check variety. A similar arrangement will be set up beyond five years. “The proposed protocol for grass maturity testing is currently being evaluated by the Association of Official Seed Certifying Agencies (AOSCA) and the USDA Plant Variety Protection (PVP) groups for acceptance within their systems,” Smith said of the next steps. This article appeared in the August/September 2024 issue of Hay & Forage Grower on pages 16-17. Not a subscriber?Click to get the print magazine. |