“Sweet hay” may help avoid hot hay |

| By Wayne Coblentz |

|

|

|

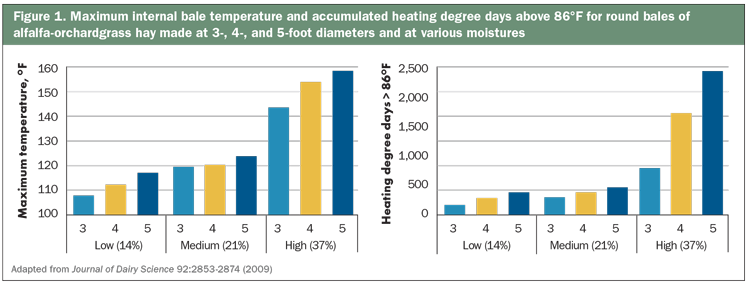

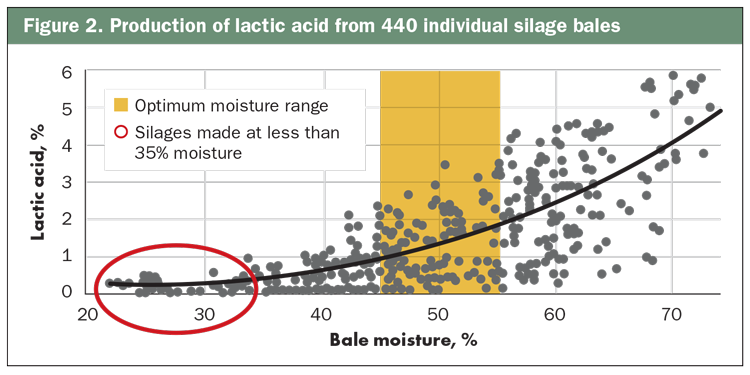

The author is a retired research dairy scientist/agronomist with the U.S. Dairy Forage Research Center in Marshfield, Wis.  Making dry hay when weather conditions are uncooperative can be extremely frustrating. These frustrations are compounded further in high humidity environments and/or cooler regions of the country, since both of those environments slow the rate at which mowed/conditioned forages dry down. Further, modern large-round or large-rectangular balers produce densely packed bales that are more likely to heat if not sufficiently dried for safe storage. Although affected by many factors, larger hay packages are more sensitive to spontaneous heating, largely because more dry matter (DM) is packaged within each bale and there is less surface area per unit DM to allow bales to dissipate water and heat. To visualize this concept, consider data presented in Figure 1. Large-round bales of alfalfa-orchardgrass hay were baled at the University of Wisconsin Marshfield Agricultural Research Station in three bale diameters (3, 4, or 5 feet) and at various moisture concentrations. To simplify the presentation, moisture concentrations have been grouped into three categories, defined as low (≤ 17%), medium (18% to 24%), and high (> 25%). Overall means for these moisture classifications were 14%, 21%, and 37%, respectively.  The high moisture designation is obviously not recommended for dry hay but is included here for illustrative purposes. However, it falls well below a typical recommended range for baled silages (45% to 55%). In Figure 1, the maximum internal bale temperature rose with bale diameter within each moisture classification. Perhaps more importantly, the inability of these large bales to dissipate heat is also shown graphically as an accumulation of heating degree days > 86°F (HDD) during storage. HDD represents a single number that integrates both the magnitude and duration of heating and can be interpreted for this discussion as simply “heat” or “heating units” incurred during bale storage. While HDD increased with bale diameter at each moisture classification, this became particularly problematic with the poorly managed high moisture hays. It is also important to note that all bales in this study were stored outdoors, where air movement provides some gradient for heat dissipation that would not exist if the same bales were packed tightly in stacks or in a barn. The type of spontaneous heating illustrated in Figure 1 also has a profound negative effect on forage quality, and in extreme cases, can lead to spontaneous combustion. Forage quality is usually impaired because the most digestible portions of the forage (sugars and other cellular contents) are oxidized in the generation of heat, leaving greater percentages of the less digestible fibrous components that are largely inert. A possible solution While various preservatives — most commonly propionic-acid based products — have been used with some success to curb spontaneous heating in hay, they are not a complete remedy for the problems summarized in Figure 1. Some forage producers have identified the concept of making low-moisture baled silage, commonly referred to as “sweet hay,” as an alternative production approach. To provide some background for the following discussion, consider Figure 2, which shows the relationship between production of lactic acid and initial bale moisture for 440 silage bales obtained from 12 experiments conducted at Marshfield, Wis. As most silage producers are aware, lactic acid is the most desirable fermentation acid because it is the strongest acid produced and most capable of facilitating a low (acidic) final pH in the silage. Figure 2 illustrates that moisture is essential for silage fermentation. In this summary, it alone explains about 60% of the variability in lactic-acid production across a very wide range of initial bale moistures (about 20% to 75%). This relationship is likely closer than illustrated in Figure 2 because the 12 experiments included multiple forage types and mixtures as well as numerous ill-advised experimental treatments that were included for research purposes. No adjustment was made for any of these factors.  The normally recommended moisture range for baled silages is about 45% to 55%, and baled silages made below that range exhibited limited or restricted production of lactic acid. Within the red circle that includes silages made at less than 35% moisture, lactic-acid production was highly restricted and frequently undetectable. This begs obvious questions, including, “Are these very dry silages well-preserved and suitable for feeding to livestock?” The answer is “yes.” In fact, all of the silages summarized in Figure 2 were consumed by livestock, mostly at the research station. However, producers should understand that the acceptable preservation of these silages is not based on normal silage fermentation, but predominantly on the simple exclusion of air. Aside from coping with the frustrating nature of uncooperative weather, there are several reasons why baling dry silages may be attractive. Some of the most prominent are:

It must be emphasized that most of these potential benefits are dependent on exclusion of air (oxygen), proper application of silage plastics, and the continuing integrity of the silage plastics during storage. In truth, the concept of making dry silages can be counterintuitive and often runs contrary to conventional thinking or bias within the silage industry, which often prioritizes formation of desirable fermentation products. A direct comparison To investigate the concept of producing dry baled silage or sweet hay, a research trial was recently conducted at Marshfield. Large round (4×5-foot) bales of mixed forages (66% legumes and 31% cool-season grasses) were baled at about 26% moisture, which is considerably below the recommended moisture range for baled silages but clearly still too wet for large bales of dry hay (see Figure 1). Half the bales were wrapped individually with seven layers of stretch plastic film, while the other half remained unwrapped. All bales were positioned outdoors on wooden pallets over a concrete pad and stored for 84 days before terminal sampling. For full disclosure, half of the bales of each type were treated with a propionic-acid-based preservative, but those effects are ignored here for simplicity of presentation. During storage, the maximum internal bale temperature for unwrapped bales continuously exposed to air was 143°F, while the corresponding temperature within wrapped bales was only 107°F. Note that a mild rise in temperature in wrapped silage bales is expected and is caused by the initial respiration of trapped oxygen within each bale until anaerobic conditions are established. Figure 3 further illustrates the accumulated heating units (HDD) at 30, 45, and 84 days of bale storage, which were more than 6.5 times greater in unwrapped bales (1,318 versus 200 HDD) after 84 days of storage. Predictably, based on the dry nature of these wrapped silage bales, fermentation was severely restricted. The average concentration of lactic and total fermentation acids was only 0.32% and 0.98%, respectively, and the final pH (5.9) was reduced by only 0.29 pH units from its initial prestorage value.  The “sweet” alternative From a producer perspective, a priority might be the subsequent effects of wrapping (excluding air) on the final quality of the forages (see Table 1). The effects of greater heating in unwrapped bales were most evident in significantly elevated concentrations of structural plant fiber (neutral/acid detergent fiber and lignin) as well as heat-damaged protein (ADICP). Concentrations of ADICP (13.9% of crude protein [CP]) more than doubled in unwrapped bales compared to prestorage values and exceeded the commonly used threshold (10% of CP), indicating significant heat damage. Perhaps most importantly, the final calculated energy density (total digestible nutrients [TDN]; net energy of lactation [NEL]) of unwrapped bales was reduced by 5.5 units of TDN (62.4% versus 59.6%) or 0.06 Mcal per pound NEL relative to prestorage values. In contrast, the final energy density of wrapped bales did not differ statistically from prestorage values. The results of this study indicate that despite minimal evidence of fermentation, spontaneous heating can be minimized by the application of stretch plastic film, thereby preserving the nutritive value of the forage. Although the concept of wrapping relatively dry silage bales appears viable, it should be emphasized that there is limited published research to support this production approach. The use of silage plastics also incurs significant additional expense. The results described here should not be interpreted as a recommendation, but rather as a possible additional option. This article appeared in the January 2025 issue of Hay & Forage Grower on pages 12-14. Not a subscriber?Click to get the print magazine. |