What’s that tiny alfalfa seed worth? Plenty!

Though diminutive, the lowly alfalfa seed contains every genetic instruction for that plant to grow into a hearty, deep-rooted perennial legume, capable of multiple harvests, high yields, high persistence, and high quality. Yield, pest resistance, winter survival capability, and quality are (potentially) all there at planting.

Or not . . .

Poor quality, run-of-the-mill, variety not stated (VNS), uncertified, or poor genetic background seed will set back production for years. Plant breeders have spent entire lifetimes to develop improved lines that yield more and have better pest resistance, unique traits, and higher quality. The average variety takes five to 10 years to develop. Take advantage of these extensive breeding efforts.

I’ve found that many growers will almost automatically choose the cheapest seed available. Is that wise? Is it worth it to buy an improved line, even if it’s more expensive?

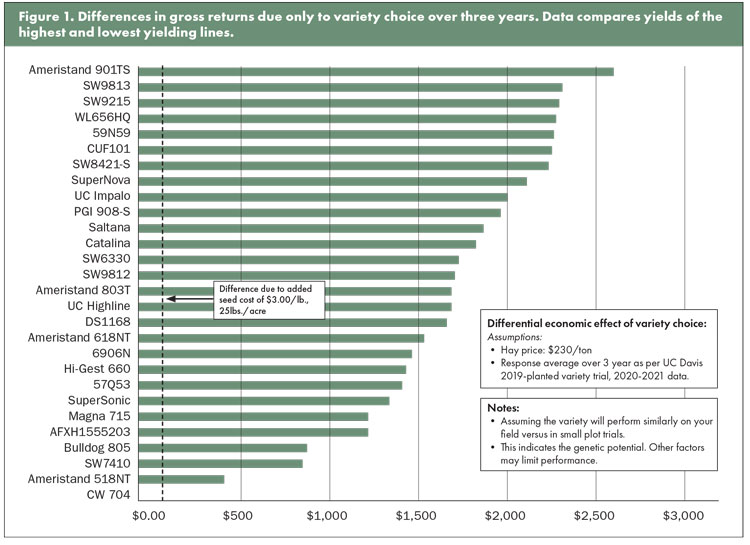

A quick economic comparison will help with that question. Take a look at the economic return on investment due to yield over three years (Figure 1). The potential return from just choosing an alfalfa variety ranged from a few hundred dollars per acre to over $2,000 per acre over three years of production. As Taylor Swift might say, “Performance is everything.” My grandkids will forgive me for quoting her.

This return is based only on the yield difference due to variety, assuming alfalfa is valued at $230 per ton. Note that even a $3 per pound difference in seed price is pretty meaningless in comparison with the economic variability in yield.

Real differences

Can you tell the genetic yield potential of varieties after planting just by looking at your field? Not really. Walking into the alfalfa field behind my house, I cannot tell whether the variety was the best performing or not, even if it looks good. To tell the difference in alfalfa cultivars, you need them planted side-by-side, replicated to account for soil variation, and adjusted for moisture. This is how we’ve conducted the variety trials I’ve planted over the past 30 years. The trial we planted this fall contains 42 lines that are highly replicated. Even when planted side-by side, they are difficult to tell apart, but over six to eight cuttings and averaged over years, the yield differences prove significant.

But is yield the whole story?

Absolutely not. Many other traits are contained in that tiny seed. Advanced lines also contain genes for resistance to insect pests and diseases, genes for winterhardiness, salinity tolerance, traits for enhanced winter growth (fall dormancy), and some have transgenic traits. While alfalfa varieties may superficially look similar, each variety is really a population of plants with widely divergent genetic backgrounds. Improved varieties have an average yield or other characteristics that may be superior or inferior to other lines.

So, how do you choose an alfalfa variety? Here are some steps that might help:

Start with yield potential. As illustrated in Figure 1, economic returns due only to yield differences can be worth a lot of money over many years. Traits such as winterhardiness, disease and insect resistance, and persistence are all reflected in a long-term yield estimate. Yield is more important than forage quality in economic returns in our estimates. Get the best local yield data you can find.

Choose a variety with an appropriate fall dormancy and winter survival rating. Fall dormancy (FD) is the degree of winter activity of varieties in the late summer and fall due to short days and lower temperatures. In California, we grow FD levels of 6 to 9 in some areas, FD 8 to 11 (very non-dormant) in other areas, and dormant varieties in the colder, high-elevation regions (FD 3 to 4), which are more similar to the upper Midwest and Northeastern states. Fall dormancy is somewhat related to winter survival, but it’s a separate test. Fall dormancy ranges from a rating of 2 (very dormant for Northern regions) to 10 (very winter active for Southern desert areas), and has a major effect on yield potential, quality, and persistence. Winter survival ratings of 1 and 2 will indicate greater winterhardiness than other lines.

Consider genetically engineered traits. A key question is the importance of genetically engineered traits. Currently, there are two such traits: Roundup Ready (RR) and HarvXtra. The RR trait should be considered in comparison with the current ability to control weeds on the farm, weed impacts on yield and quality, and the cost of other herbicides used over three to six years of production.

The HarvXtra trait, which is always stacked with RR, has its best fit with the goal of obtaining high yields with delayed cutting while still obtaining highly digestible forage. So, the economics of those traits is somewhat different than a simple yield comparison, depending upon the need for high quality and an effective herbicide program.

Examine pest and disease resistance. Alfalfa generally has the widest range of pest resistance of any major crop, probably due to the depth of variation available for selection in alfalfa populations. Some of the key disease resistances are verticillium wilt, bacterial wilt, fusarium wilt, and anthracnose. Key insect and nematode resistances are the aphid complex, potato leafhopper, and stem and root knot nematodes. Should one consider all of these equally?

Not really. It’s important to determine the key pests in your region and emphasize those. For example, potato leafhoppers are not a large problem in many of our California locations but are very important in many Midwestern locations. Blue alfalfa aphid (BAA) is important in many of our areas but doesn’t seem to be a big problem in the Northeastern U.S. Verticillium wilt is a key problem in the Pacific Northwest and many other locations, but we really haven’t seen it in the low-desert environments.

Keep in mind that resistance is not absolute but relative, and a disease or insect can overwhelm the resistance in a variety under certain conditions. Think of pest resistance as auto insurance — you may not need it every year but might really need it when conditions for the pest are ideal.

Make an informed choice. As indicated above, start with a good comparison of yield, hopefully with an independent test such as the one in Figure 1. Unfortunately, the university-type trials have largely gone the way of the dodo bird in recent years, due largely to consolidation in the seed industry and the cost of running trials. Ideally, these types of trials should be funded by growers, but that has not happened. There is still information out there, though. For yield data, some states (such as California) maintain online yield information (see alfalfa.ucdavis.edu). The second step, in my view, is to do your own strip tests on your farm with perhaps three or four lines that are good candidates. Seed marketers also have in-depth knowledge of their varieties.

For pest resistance and other traits, see the National Alfalfa & Forage Alliance Alfalfa Variety Ratings 2024 bulletin (www.alfalfa.org or the November issue of Hay & Forage Grower). There is a lot of information contained within the publication.

Stave off low production

Variety choice is clearly an important aspect of successful alfalfa production. However, as many growers know, a good variety is only as good as the production practices on a farm. It’s clear to me that many of these practices, such as good stand establishment methods, optimum soil fertility and health, drainage, harvest timing, and sound irrigation strategies are critical for top production — probably more so than the variety choice. However, all are important.

In the 1800s, Justus von Liebig put forward in his “barrel stave” analogy, known as the law of the minimum. Water volume (or in our case, alfalfa yield) in the barrel is limited by those barrel staves that are shortest. For alfalfa, we are limited by those agronomic factors that are the scarcest (water, phosphorus, potassium, micronutrients, temperature, and so forth). This may also include the genetic potential of that variety, which is dictated by variety choice.

So, take some time to choose a variety by studying information available and do strip tests on your farm. We should all agree that the variety need not be the shortest stave in the barrel.

This article appeared in the January 2024 issue of Hay & Forage Grower on pages 18-20.

Not a subscriber? Click to get the print magazine.