In 2015, the average price of raising a dairy heifer in Wisconsin was $2.77 per day. In 2023, farmers reported paying as much as $3.15 per day. The result — in addition to other expenses and lower milk prices — has been a trend of diminishing profits. The million-dollar question is: Can anything be done to stop this trend?

If raising replacement heifers is such a large expense and over 50% of those expenses come from feed costs, the question should be: How can we reduce the costs of producing quality feed for dairy heifers?

While improvements in forage yield, quality, and harvesting efficiency can have direct impacts on the milking herd, these factors don’t necessarily transfer to the heifer program. In many cases, prioritizing high-quality forage production can add unnecessary costs to heifer production. So, what if the greatest opportunity to address the high cost of heifer raising involved taking a step back to the dairy industry’s grazing roots?

Curb the high costs

Our attention has turned to what’s below the soil surface, from nitrogen-fixing crop roots to cover crops creating root channels and the continuous living roots of perennial forages. While these types of roots all carry potential to create resilience into our farming systems, there are roots of a different kind that are just as critical to the long-term success of our farming systems — the metaphorical roots of raising livestock on the land.

Domestication of grazing ruminants was one of the first forms of agriculture, and managed grazing is an efficient form of agriculture. We don’t have to dig too deep into history to recall a time when nearly all dairy cattle spent summers on pasture, but a drive through today’s countryside will show that most dairy farms don’t graze cattle anymore. The push for greater milk production and efficiency caused grazing to fall out of favor to more precise methods of feeding dairy cattle. But perhaps there’s still a place for grazing.

The practice of well-managed grazing has the potential to unlock ecological and agronomic functions belowground and aboveground. In other words, managed grazing can produce sufficient forage yield and quality at a lower cost while nourishing livestock, protecting our resources, and ensuring profitable margins.

While the high cost of raising dairy heifers has largely been accepted as the cost of doing business, putting heifers on pasture for a portion of the year is a viable cost-reducing option worth considering. In fact, UW-Madison’s Dairy Heifer Compass (grasslandag.org/tools/) estimates that moving a dairy heifer to pasture for 180 days could save a farmer $1.67 per head per day. That’s a 47% cost reduction!

Focus on the forage

Research has shown that it’s possible for dairy heifers raised on pasture to meet the performance standards set for those raised in confinement while improving environmental outcomes and farmer profitability. Managed grazing begins with establishing a forage base that is well-suited to the land. While orchardgrass and smooth bromegrass once dominated the dairy landscape, today’s farmers have access to a greater selection of improved grasses and legumes. Not only do some species thrive under grazing conditions, but plant breeding efforts have boosted forage yield and quality potential of some varieties to the extent that heifer nutrient needs can easily be met on pasture.

Cool-season grasses are often underappreciated because they are commonly managed in systems that don’t allow them to express their full yield and quality potential. However, trials at the UW-Madison’s Marshfield Agricultural Research Station have confirmed the potential of cool-season grasses when managed in a system with 30-day rest periods between five grazing events.

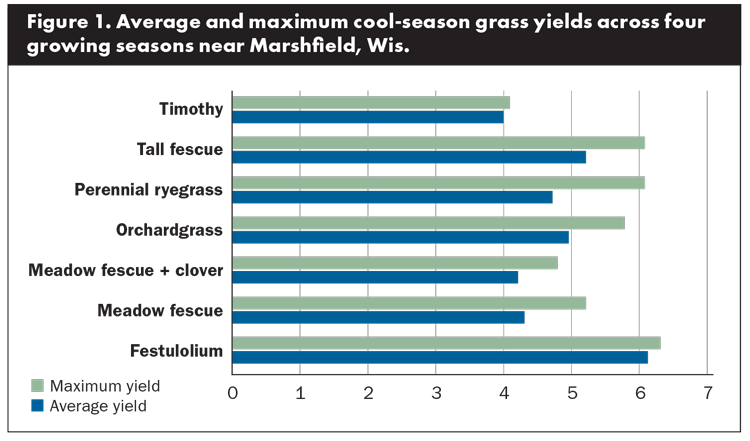

Varieties of meadow fescue, orchardgrass, perennial ryegrass, tall fescue, timothy, and grass-legume mixes have consistently produced 4 to 5 tons of dry matter per acre (Figure 1), had relative forage quality (RFQ) measurements of 150, and had 48-hour neutral detergent fiber digestibility (NDFD48) of 70%, which are well within the nutrient needs of a dairy heifer.

Be careful not to confuse managed grazing with other forms of grazing. A continuously grazed pasture or drylot is not managed grazing, and this confusion can lead people to avoid grazing dairy heifers. We refer to the foundational principles that make managed grazing unique as the “Three R’s.”

Rotation. A critical part of maintaining forage growth is the grazing rotation. In managed grazing, livestock occupy a paddock for short durations. In many cases, heifers are moved every one to three days, depending on pasture setup. This allows livestock to only graze the highest quality portion of forage and does not force them to graze any lower, which protects plants and ensures heifers are getting the best nutrition.

Rest. Similar to alfalfa, grass requires a sufficient regrowth period to restore carbohydrate reserves depleted from grazing. Most cool-season grasses need about 30 days of rest for proper regrowth if there are no severe environmental stressors. Grazing sooner than this, or repeated overgrazing, can deplete carbohydrate reserves and reduce overall forage productivity.

Paddocks can withstand high stocking densities for a short duration, but adequate pasture acreage must be available to allow for at least a 30-day rest period between grazing events. For example, a typical grazing season in Wisconsin spans from early to mid-May through early November. These are months when heifers are feeding themselves and spreading their own manure. The savings are not only in feed costs, but in labor, fuel, and equipment use.

Residual. The foundation of any successful grazing system is a solid base of perennial grasses and legumes, but the way forage is managed differentiates managed grazing from just letting the cows out of the barn. Always leave the bottom 4 to 6 inches of plants ungrazed. The goal is to leave up to 50% of the available forage in the field to jumpstart regrowth during the rest period. If the pasture is grazed too short, aboveground regrowth will be stalled for two to three weeks while the plant restores carbohydrate reserves depleted from overgrazing.

Why not try it?

Grazing dairy heifers can be a complex change that brings with it some uncertainties, such as animal performance on grass compared to a mixed ration, building fences, and converting cropland to pasture. But farmers are finding innovative ways to take advantage of this cost-saving practice that also benefits their land and the environment.

Annual cover crops and crop residues provide alternative opportunities to graze heifers for a period of time without having acres dedicated to pasture. Moreover, some farms are moving to heifer grazing as a sole enterprise, providing custom heifer grazing as a service to other dairy farms. Perhaps the future involves us going back to our roots by grazing dairy heifers, contributing to a more resilient and prosperous future for dairy.

This article appeared in the March 2024 issue of Hay & Forage Grower on page 18.

Not a subscriber? Click to get the print magazine.