High-quality corn silage and alfalfa and grass forages are staples on dairy farms; however, these feedstuffs provide inadequate fiber and excess energy for breeding-age and pregnant dairy heifers.

High-quality forages are well-suited for young heifers up to 8 months old due to these animals’ lower feed intakes and higher energy needs around 62% to 65% total digestible nutrients (TDN). Yearling and pregnant heifers have higher feed intakes, so their diet energy needs are lower at about 58% to 60% TDN, which is far less than the typical 65% to 75% TDN that corn silage and alfalfa haylage can provide.

Ideally, large-breed heifers like Holsteins should gain 1.8 to 2.2 pounds of body weight per day to meet target weight goals. But studies show that feeding a diet of corn silage and alfalfa haylage with 45% neutral detergent fiber (NDF) and 65% diet TDN causes heifers to gain 2.5 pounds per day or more, leading to greater fat deposition.

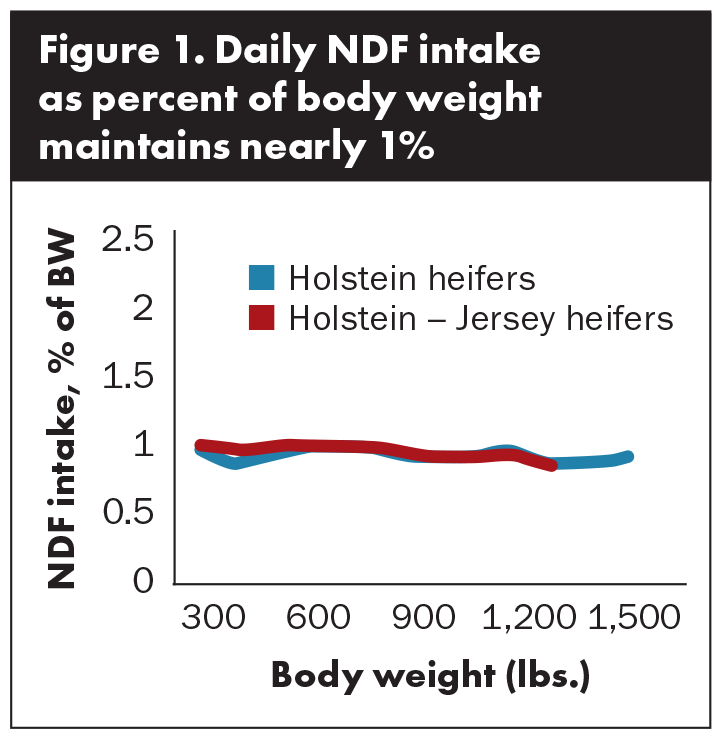

To remedy this, researchers at the University of Wisconsin (UW) Marshfield Agricultural Research Station have evaluated options to control heifer growth for several years. Pat Hoffman, a retired UW dairy management specialist, compiled data from over 9,000 daily pen intakes and found heifers across a weight range of 300 to 1,500 pounds ate approximately 1% of their body weight as NDF each day due to the nutrient having a filling effect in the rumen (Figure 1).

For example, a 1,000-pound heifer is estimated to eat 10 pounds of NDF daily. If that diet contains 45% NDF, the heifer will eat 22 pounds of dry matter (DM); however, at 50% NDF, she will eat 20 pounds of DM. At 55% NDF, the heifer will eat 18 pounds of DM. With this information, we can use higher fiber forages to formulate diets to control feed intake and weight gain in dairy heifers while also reducing feed costs.

We have found using various forages to elevate the diet NDF to 50% to 55% and keeping energy levels at 58% to 60% TDN has allowed gains of 1.8 to 2 pounds per day for bred and pregnant heifers. The type of forage used really does not matter with a variety of options available and species selection dependent on the individual farm.

Wait for bloom stage

Although we want to make the highest quality forage possible, there is a case to be made for allowing a cutting of alfalfa or grass to become more mature at specific times of the year. Having a staggered harvest schedule with a longer growing interval for one summer cutting — 35 days or more at 50% bloom instead of 28 days at bud stage — may be beneficial for the plants and for forage yield.

A longer interval allows plants to better restore root or stem reserves and improves later regrowth and yield. Also, forage quality decreases more quickly during the summer, favoring its use in heifer rations. This strategy likely would be implemented on select acres, such as older stands, to meet inventory needs for high-fiber forage by getting more yield. It could also possibly be practiced across additional acres to promote a stand’s lifespan. A useful resource on alfalfa harvest strategies is available at bit.ly/HFG-alfalfa-harvest.

Try warm-season annuals

Forage sorghum, sorghum-sudangrass, and millets are becoming more commonly grown. Conventional varieties have ideal fiber and energy contents to blend with a moderate-quality haylage in pregnant dairy heifer diets to meet animals’ nutrient needs. Harvest strategy has a big effect on yield for these forages, with a single harvest producing 1.5 to 2 times more biomass than a two-cut system.

At the UW Marshfield and Hancock research stations, conventional forage sorghum and sorghum-sudangrass planted in early June and harvested in October or early November yielded 6 to 8 tons of DM per acre, while two-cut plots had yields of 3 to 4 tons of DM per acre, although this forage had higher digestibility and protein.

Any producer who has worked with forage sorghum knows moisture content at harvest can be a challenge. A conventional variety should mature and be ready to harvest by mid- to late October, but photosensitive varieties will need to be frost killed and dried over one to two weeks, which brings a risk of lodging.

To minimize the risk of lodging, harvest the crop prior to or after corn silage harvest using a cut and wilt strategy. This is a good option for either conventional or photosensitive varieties. An earlier harvest also opens opportunities to apply manure and establish a cereal grain crop for harvest the following spring.

Potential for perennials

The use of perennial warm-season grasses by dairies is minimal due to low forage quality; however, this makes them ideal for feeding heifers or dry cows. Switchgrass has been a focus for biofuel research and can be grown in various soils and climates. Newer varieties with faster establishment to improve first-year growth and reduce weed competition are being developed by Roger Samson with the Resource Efficient Agriculture Production-Canada.

Canadian researchers have found that after the establishment year, switchgrass yields can be over 6 tons of DM per acre with a single harvest in early fall. Canadian producers are currently using switchgrass forage for replacing straw in dry cow rations and also for bedding, which may offer additional cost saving opportunities.

Eastern gamagrass is another option, and these plants have had persistence over multiple years at the Marshfield Agricultural Research Station. Using a mid-September harvest, yield was maximized at 3 to 4 tons of DM per acre with forage quality of 75% NDF and 5% to 7% protein. Dry matter content was 30% to 40%, so minimal to no wilting time was needed prior to harvest.

Potassium content of single-harvest warm-season grasses is generally low at 1% to 1.5%, making them suitable to replace straw in dry cow rations. Perennial warm-season grasses also have the advantage of lower establishment costs with stands expected to produce for several years.

Roughages like straw and stover can also work well in heifer rations, so producers have several options to produce higher fiber forage. Before managing a new species, get advice from your agronomist, extension staff, nutritionist, and other producers about best management practices and estimating forage inventory needs and diet formulation.

This article appeared in the March 2024 issue of Hay & Forage Grower on pages 12-13.

Not a subscriber? Click to get the print magazine.