The climate of the U.S. hay export market has gone from good to difficult to different. Different, or strange, according to Scot Courtright, who explained how trade has changed over the past few years at the California Alfalfa & Forage Symposium in Sparks, Nev.

Courtright is the owner of Courtright Enterprises, an export company based in the Columbia Basin, where he oversees logistic operations and international sales. He said hay exports this year have largely been influenced by three things: an uptick in West Coast imports, trade conflicts on the Red Sea, and demand shifts from individual markets.

There are two major reasons for greater import volume on the West Coast, Courtright said. For one, importers are trying to get ahead of potential tariffs proposed by the Trump administration, causing a surge in incoming shipments. Secondly, even though the East Coast’s International Longshoremen’s Association (ILA) formed a new contract agreement following port strikes this fall, another union strike will likely occur there early in the new year.

“More volume has shifted to coming into the U.S. on the West Coast because of the challenges and the fear of strike or turmoil on the East Coast,” Courtright explained. On the contrary, the labor union on the West Coast signed a contract negotiation last year, which should mitigate the risk of port strikes there for at least five years.

Crisis on the Red Sea

In addition to where shipping containers are arriving, the route they are taking has changed as well. Rebel attacks in the Red Sea have disrupted trade through the Suez Canal, which accommodates the vast majority of the cargo from Asia to Europe, the largest trade route in the world. These attacks have eradicated insurance for vessels through the Red Sea, prompting a reroute around the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa, adding three weeks of transit time.

Following the COVID-19 pandemic, shipping rates significantly declined. In fact, Courtright notes rates that previously hovered around $7,000 per full container dropped to nearly $1,200. This was largely unprofitable for ocean carriers, which consequently started to pull services; however, Courtright contended the conflict in the Red Sea and extended shipping route has actually helped the situation by keeping ocean services intact.

“The powers that be are allowing the situation in the Suez Canal to continue, because if the canal were to open up completely, ocean rates would likely drop significantly as there would be an overwhelming surplus of capacity,” he said.

The big three

After discussing shipping logistics, Courtright detailed the current environment of each major export market.

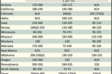

Japan is the largest export market for all hay, including roughly 500,000 metric tons (MT) of alfalfa, 300,000 MT of timothy, and various other types of grass hay and straw every year. With that said, as the U.S. dollar has strengthened with rising interest rates, the exchange rate between the Japanese yen has skyrocketed, significantly impeding the Asian country’s buying power.

Japan is currently importing about 85% of what it did five years ago. Timothy hay exports to Japan stalled with high prices during most of 2024, but Courtright predicts these prices, and thus demand, are on the mend. Alfalfa exports to Japan are also looking up compared to last year as dairies there are feeding cows more alfalfa; however, neither grass nor alfalfa volumes are expected to reach so-called normal levels.

“The remaining 15% is likely gone for some time,” Courtright asserted. This prediction was based on government subsidies that are encouraging Japanese dairymen to grow and feed homegrown forage.

South Korea is the largest grass straw export market for the U.S. Courtright said trade dynamics between South Korea appear to be healthy despite political turmoil in the Asian country, with exports rebounding to nearly 100% of typical levels. He also noted the South Korea’s quota system for grass hay will be completely phased out by 2026, which may benefit future trade.

China is the largest export market for U.S. alfalfa hay; however, it was the market with the single largest decline in volume last year. Courtright said Chinese milk prices have slid for 40 months straight as the dairy industry there crumbles. Roughly 60% of the Chinese dairy industry was unprofitable in 2023, and that number jumped to 80% in 2024. And as Chinese producers reduce their herd size, it’s not a good sign for the amount of alfalfa they will need.

Chinese-owned companies based in the U.S. have also influenced export volume as of late. Courtright said about 30% to 40% of hay volume shipped to China each month funnels through these companies, making that product inaccessible to exporters. This doesn’t necessarily threaten hay growers, Courtright said, but it definitely throws a curveball in the export market.

The final change in trade with China has been shipping logistics. What used to take two weeks to ship hay directly from the West Coast to northern China ports now takes about a month as main vessels must be transferred to smaller vessels throughout inner Asia.

Final thoughts

As other countries expand hay production, Courtright suspects U.S. customers may begin buying from more reliable sources. “The U.S. has been looked at over the last several years as an unstable place to supply from due to a lot of our labor issues and volatility in our pricing,” he said.

On the other hand, Courtright pointed to government programs in Middle Eastern nations that are eliminating feed crop production in favor of more food production for human consumption. As these laws gain footing, demand may improve with a more diversified customer profile. Even so, Courtright said the largest opportunity lies in India, where U.S. alfalfa is in the midst of being approved.

Overall, Courtright purported the worst is over in terms of low exports out of the West as volumes trended higher this year and look to continue to climb. He is hopeful that trade negotiations led by the incoming administration will enable a better outlook next year as well.