For those in areas of the country where winter actually exists — real snow with drivable lakes — you’ve been looking at brown or white alfalfa fields for several months.

All of that is about to change . . . hopefully.

It’s that time of year when the sight of new, green alfalfa shoots is as welcomed as the Publisher’s Clearinghouse people on the front doorstep. Conversely, there is also the other scenario when green is nowhere to be found and reality sets in that Mother Nature has brought the equivalent of a 60 Minutes camera crew to the front porch.

Those are the two extremes and the easiest two scenarios by which to make an alfalfa stand decision for 2016: keeper or goner.

There are many situations every year when an alfalfa stand falls somewhere between. This is when the decision becomes more difficult because there are multiple shades of winter injury.

Look, then look again . . .

Perhaps one of the more important lessons to be learned when evaluating alfalfa stands for injury in the spring is to check stands more than once before determining a final prognosis. Sometimes plants will begin to green up and grow but later die off. This can be caused by numerous factors including low root carbohydrate reserves, severe frost injury or disease.

In contrast, plants that green up and continue growing may still have suffered winter injury. These plants often exhibit one or more of the following characteristics:

· Slow green up: One of the most evident results of winter injury is that stands are slow to green up. If other fields in the area are starting to grow and yours is still brown, it’s time to check those stands for injury or death.

· Asymmetrical growth: Buds for spring growth are formed during the previous fall. If parts of an alfalfa root are killed and others are not, only the living portion of the crown will give rise to new shoots, resulting in a crown with shoots on only one side.

· Uneven growth: During winter, some buds on a plant crown may be killed and others may not. The uninjured buds will start growth early while the killed buds must be replaced by new buds formed in spring. This will result in shoots of different height on the same plant, with the shoots from buds formed in spring several inches shorter than the shoots arising from fall buds.

· Root damage: The best way to diagnose winter injury is by digging up plants (4 to 6 inches deep) and examining roots. Healthy roots are firm and white in color with little evidence of root rot. Winterkilled roots have a gray, water-soaked appearance early, just after soils thaw. Once water leaves the root, the tissue becomes brown, dehydrated and stringy.

If the root is soft and water can be easily squeezed from it, or is brown, dry and stringy, it is most likely winterkilled. Also, if 50 percent or more of the root is blackened from root rot, the prognosis for long-term productivity is highly questionable.

If stands are winter injured . . .

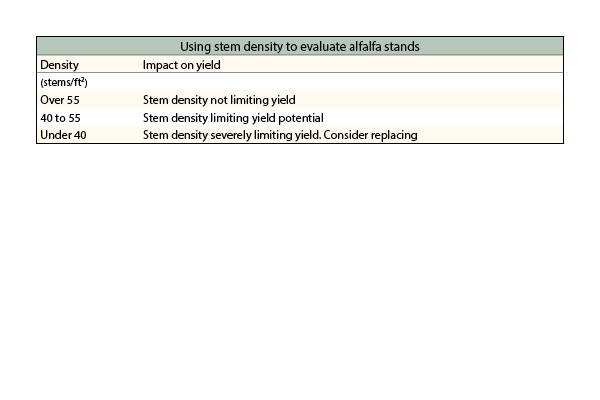

Winter-injured stands are often more difficult to evaluate from the standpoint of what to do next compared to winterkilled stands. It often comes down to accepting something less than full-yield potential but more than what might be obtained from a new seeding. The table below was derived from University of Wisconsin research and offers guidelines to evaluate yield potential based on the number of stems per square foot.

Cutting management for winter-injured stands needs to be somewhat more conservative than on healthy stands. If possible, delay first-cut until flowering and cut fields higher than normal.