According to Wikipedia, a world-renowned authority (insert sarcasm here) on everything, the Goldilocks principle is named based on an analogy to the children's story "The Three Bears."

The tale documents a young girl named Goldilocks who tastes three different bowls of porridge and finds that one is too hot, and another is too cold. Moving on to the third bowl, she encounters porridge that is at the optimum temperature to her liking.

The concept of being "just right," or at least within acceptable limits, is easily understood and applied to a wide range of disciplines. The Goldilocks principle has been referenced and applied in numerous disciplines, including developmental psychology, biology, astronomy, economics, engineering, and . . . of course . . . agriculture.

Extremes abound

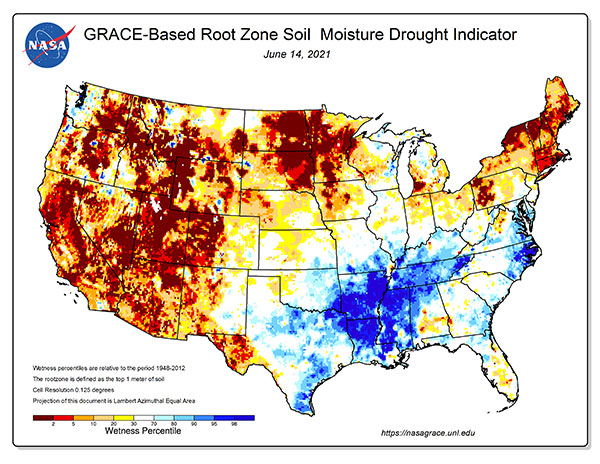

A quick look at the root zone moisture map below offers a clear picture that there’s not a whole lot of the U.S. that is “just right” from a forage growing or harvesting perspective in 2021. The folks in Mississippi, Louisiana, and Arkansas are drowning while forage vegetation in many other states is wilting, and that’s before being cut.

Unlike most grain crops, forages don’t offer much compensatory growth that is lost due to dry weather. As Kim Cassida, extension forage specialist with Michigan State University, succinctly said during a recent webinar addressing her state’s drought, “Wacky weather hammers forage yield and cumulative stress matters for perennial crops.”

Similarly, once harvest is delayed by wet weather, or wilting hay is rained on, forage quality can’t be recovered.

Fairly warned

With no mulligans for forage crops, we saw countless articles and webinars this past winter and spring on drought planning, especially for those who rely on pasture and rangeland as their primary forage resource. The message of many of these presenters was simple: “Be ready with a plan; it’s going to happen.”

Warm-season summer annuals, higher culling rates, drylotting, feed supplementation, and early weaning were all components of the drought battle plan. Of course, all these strategies are easier to implement with a little forward thinking than during the heat of battle, or, if you prefer, the battle with heat.

Even during one of those “just right” summers, cool-season grasses always take a siesta at the mid-summer pole marker. We’re all familiar with the classic growth curve of cool-season grasses and legumes: fast growing in the spring, functional but slowing in early summer, siesta to nearly dormant in mid-summer; and back to earning their keep on the payroll in late summer through fall until cold temperatures bring the season to a close.

It’s the “summer slump” that causes much of our forage production consternation each year. But in drought years such as 2021, we experience an S.O.S. (Slump On Steroids). Whether relying on stored feed or pasture, there are answers that go beyond the weatherman.

The hay debate

This past spring, while farm-hopping in Arkansas, I visited with two cow-calf beef producers who noted that they adopted a baleage system to avert a future situation like they found themselves in following the droughts of 2011 and 2012. In other words, stored feed from the good times was their drought insurance for the bad times. They had a plan.

Many of you have attended presentations where haymaking is almost villainized because of its cost compared to grazing. There’s little arguing this point, but making hay out of excess spring forage or from designated fields too far away to graze offers some reasonably cheap drought insurance when one considers the long-term cost of overgrazing pastures or selling cows when there is no other alternative.

Of course, hay can be purchased; however, drought also sends the price of hay soaring and supplies in the opposite direction. Baled hay is already selling for $30 to $50 more per ton than it was one year ago.

Maybe our 2021 weather will moderate. Maybe it won’t. In either case, it’s probably a good time to start taking notes for next year’s drought plan.