Thanks to a less than ideal growing season for many parts of the U.S., hay supplies were already meager going into the winter-feeding season. As supplies begin to run low, rationing forage inventory becomes a key factor in making sure there will be enough hay to meet livestock needs.

In the University of Kentucky beef newsletter, Off the Hoof, Associate Extension Professor Jeff Lehmkuhler outlines the steps it takes to make ends meet.

Determine hay needs

“Hay needed to overwinter a cow can be estimated relatively easily,” Lehmkuhler starts. He explains that as long as you know the mature weight of your cows, you can multiply the average weight by 3 percent and the number of days you expect to feed hay.

Lehmkuhler uses the example of a cow with a body condition score (BCS) of 5 and a weight of 1,300 pounds. You would take its weight times 3 percent to result in 39 pounds. Now assume you will be feeding hay for 150 days. Take the 39 pounds times 150 days, which results in 5,850 pounds of hay needed.

If a bale provides 800 pounds of hay, 7.3 bales per cow would be needed for the feeding period. “Always add 10 to 20 percent more due to feeding losses, spoilage, and longer feeding periods,” Lehmkuhler says. He also advises to inventory hay at the start of winter since hay will be cheaper when supplies are high rather than later when they are low.

Match hay quality to animal needs

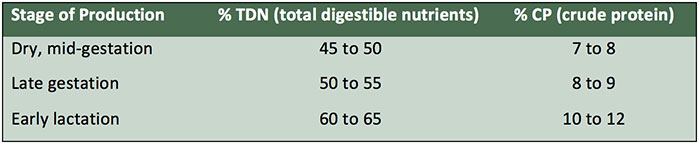

In terms of production, beef cows can be broken down into four categories: late gestation, early lactation, late lactation, and dry or mid-gestation. Each category has different nutritional needs. For cows in late gestation, 60 to 75 days before calving, the fetus is growing rapidly so the nutritional needs rise.

Once a cow calves, the nutritional needs are even higher due to high milk production. Peak milk occurs about eight weeks postcalving, and that is when their nutritional needs are the greatest. Feeding the highest quality forage during lactation will minimize condition loss and need for supplementation.

After calves are weaned and milk production ends, nutritional needs are reduced. Cows are now in the second trimester of gestation, and their nutritional needs are at the lowest of the production cycle. Lower quality forages can be used to reserve the higher quality feed for later in the season.

The table below outlines the nutritional needs for the stages of production discussed.

Restrict hay access

One way to stretch a tight hay supply is to limit the amount of time certain cows have access to hay. “This can only be done for mature cows that are in the dry, mid-gestational stage of production and have a BCS of 5 or 6,” Lehmkuhler states.

Research conducted at Purdue University shows that allowing access to hay for only eight to 12 hours per day had no detrimental impacts on body weight or condition. The study also found that hay disappearance was reduced by 15 percent.

However, that study, as well as a study completed at the University of Illinois, found that when this practice was used with young, thin, and late gestation cows, both weight gain and body condition declined.

Quality of hay also plays a role in this practice. Low-quality hay should never be fed with restriction due to the reduced digestibility and nutrient concentrations.

“If this management is used, the herd will need to be separated by age and production as lactating, late gestation, young, and thin cows should not be restricted,” Lehmkuhler advises.

Minimize hay loss

Research demonstrates that when hay is unrolled and fed on the ground, there is a high level of loss and spoilage due to trampling and contamination from mud and manure.

Lehmkuhler recommends using hay rings. Rings with sheeting around the bottom that keep bales elevated but allows loose hay to fall within the feeder is the best option to negate losses. “These feeders are more expensive up front, but if hay is expensive, they can lower feeding costs,” Lehmkuhler explains.

While hay feeders do help reduce hay loss, they still need to be monitored. If hay builds up in the feeder and the cows don’t eat it, hay can rot or mold. If the hay is high quality, allow animals to consume the hay lying on the ground within the ring before adding a new bale because buildup can elevate losses due to molding or rotting.

Placing hay rings on a feeding pad is another consideration that will further minimize hay losses.

Replace hay with other feedstuffs

If needed, replacing hay with other feedstuffs to supply nutrients is feasible. But be warned; rumen fill will become an issue as stretch receptors will not be triggered. Cows will continue to seek food even though their nutrient needs have been met. Providing access to low-quality forage, such as corn stover or wheat straw, ad lib can help with gut fill.

For example, tall fescue hay typically has 45 to 50 percent TDN (total digestible nutrients) and 7 to 9 percent CP (crude protein) on a dry matter basis. One pound of distillers grains supplies the same amount of protein as 3 to 4 pounds of hay as well as the energy to replace 1.75 pounds of hay.

For dry cows, soybean hulls can replace grass hay at a rate of 1.5 pounds of hulls per 1 pound of hay. However, at least 8 to 10 pounds of long-stem forages should be fed to maintain rumen function.

Water should also not be overlooked. A beef cow needs 10 to 20 gallons of water a day. If access to water is restricted, intake and milk production will be reduced.

A high-quality, loose mineral should also be available to ensure vitamin and mineral requirements are met. If a supplement is fed, consider including an ionophore such as monensin. Research has shown that cows will maintain a similar BCS on 5 to 10 percent less feed when fed 200 milligrams of monensin per head per day.

Kassidy Buse was the 2018 Hay & Forage Grower summer editorial intern. She is from Bridgewater, S.D., and graduated from Iowa State University with a degree in animal science. Buse is currently attending the University of Nebraska-Lincoln pursuing a master’s degree in ruminant nutrition.