Weather extremes are typical for many of our Northwestern states, but the last two years have taken those extremes to a new level.

“In some parts of the Northwest, this is the second year of drought, and drought areas tend to draw hay resources,” noted Jon Paul Driver during a Hay Market Outlook webinar presented by Northwest Farm Credit Services.

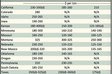

Driver pointed to Montana as a state where hay stocks were severely cut during a 2020 drought and then experienced an even more severe drought in 2021. He thinks it will take a couple more years of average or better production before the Montana hay market normalizes to predrought levels.

The widespread impact of the drought is chronicled in the fact that nearly every state in the Northwest is projected by USDA to have lower grass and alfalfa production this year compared to last. Dryland production was hit especially hard.

Most experts, including Driver, have struggled to explain a large bump in USDA-projected California alfalfa production in 2021, especially with the high temperatures and rationed water experienced during the summer. “High temperatures offend irrigated production as well as dryland production,” Driver noted. “There was also a lot of smoke from the wildfires that hindered hay production.”

The hay market analyst also questioned the USDA estimate for Oregon alfalfa production in 2021, which was essentially the same as 2020. “We know water was shut off in many areas, including the Klamath Basin,” he said. “Ultimately, I expect a lower number for Oregon.”

High temperatures during the summer made it especially difficult to bale hay with dew. “There’s not a lot of dew generated at 118°F,” Driver noted. “There was a lot of leaf loss in Washington for second cutting. Third cutting was smoke damaged with off color and lower yields.”

Rising input prices

A lot of factors are playing into rising input prices for producers, according to Driver. He noted that the Gulf Coast hurricanes shut down production plants for an extended period, cutting the supply chain. Natural gas, which is used to produce nitrogen fertilizer, has also experienced production issues and prices have continued to climb as a result. The market analyst cautioned about possible anti-dumping tariffs on fertilizers coming from some foreign countries such as Russia and Morocco. This puts further uncertainty into fertilizer markets.

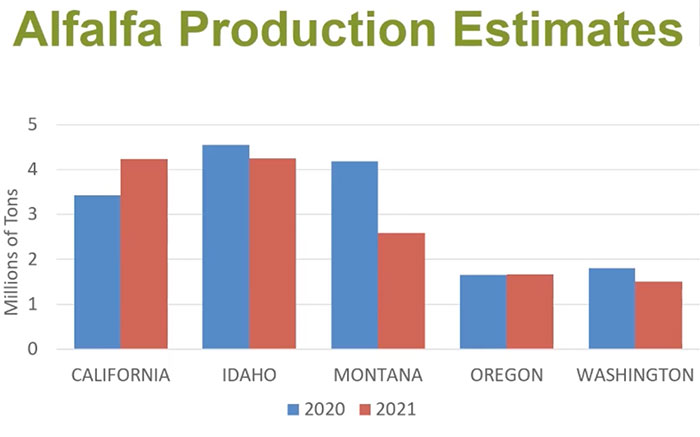

Another factor that is contributing to higher input prices relates to a massive rise in bulk and container shipping prices. The latter have increased five-fold in price during the past year, and that’s if companies can even find available containers.

Hay prices continue to climb

Using USDA Agricultural Marketing Service data, Driver pointed out that prices for Premium large square bales of alfalfa hay in the Northwest bottomed out in April at about $180 per ton and now is selling for $290. This will make it more difficult to compete on the world export market as we move forward. Timothy prices across the Northwest have shot up from about $200 per ton in 2020 to nearly $350 per ton today. “I think we’re going to see more acres planted to timothy this fall,” Driver assessed.

A mixed bag for exports

Looking at grass hay exports for the first half of 2021, Driver noted that volume was running about 3% ahead of 2020 as low-priced inventories at the beginning of the year were easier to move at lower prices. Those excess inventories have since dried up, and what is left is extremely high-priced, which Driver predicts will hinder exports in the last half of the year.

China, of course, remains the top importer of U.S. alfalfa hay and continues to purchase alfalfa at a rate far above 2020 levels. Driver explained that a trade spat between China and Australia limited the latter’s ability to export oaten hay to the former, and at least some of the shortfall in China was made up with U.S. alfalfa.

Beef culling drops demand

Driver noted that in states such as Montana with high cattle populations, he’s hearing that significant culling is taking place, perhaps up to 10%. The analyst believes that this level of culling could lead to about 250,000 tons of demand destruction for grass hay. Further, he noted that there are some positive tax implications for selling cows because income can be deferred.

“The math is different for dairy cows because less dry hay is consumed, and all of the alternative feeds are high-priced, too,” Driver said. “So, I think hay demand on the dairy side may not change all that much.”

What’s next?

Looking ahead, Driver encouraged producers to think about what can be done to manage rising production costs. “Budgets and partial budgets become really important as we look forward to next year,” Driver asserted. “Prebuying inputs has mostly been a tax strategy, but this year it might be needed just to secure inventory. Many farm chemicals will be difficult to secure in a timely fashion, just like fertilizer,” he added.

In concluding, Driver emphasized the importance of keeping good records and investing in measurement and controls. “Some of the production risk can be managed with insurance,” he noted.