The author is a retired professor and dairy nutrition extension specialist with the University of California-Davis. His email is phrobinson133@gmail.com.

Fall weather often brings cool and wet conditions that can stimulate mold growth in crops prior to harvest. This can boost mycotoxin levels in silage.

Mycotoxins are toxins produced by some molds (fungi) on plants to reduce activity of other molds or bacteria. There are hundreds of mycotoxins, all with complex chemical structures, although only a few are thought to impact mammals if they are eaten.

As most molds do not produce mycotoxins, their visual presence in a silage, or even high levels of mold spores, does not mean that mycotoxins are present — although they might be. However, molds will always, to some extent, reduce silage palatability and, because they consume the most fermentable parts of the crop, reduce its energy value.

Low levels of mycotoxins are in most silages under most conditions, and cattle frequently consume them. This is generally not a problem as rumen bacteria effectively detoxify many mycotoxins. However, if a diet is very high in mycotoxins, the ability of the bacteria to detoxify them may be overwhelmed. If this happens, mycotoxins escape the rumen, are absorbed from the intestine, and exert toxic effects on the animal. Common symptoms of this include:

- Reduced intake and milk production

- Greater frequency of ketosis and displaced abomasums

- Diarrhea in many impacted animals

- More swollen vulvas and nipples and vaginal or rectal prolapses

- Reduced fertility

- Increased early term abortions

Types to watch for

Mycotoxins found most frequently, and of greatest concern, are aflatoxin (produced by Aspergillus molds), zearalenone, T-2 toxin, deoxynivalenol (DON; a.k.a vomitoxin), fumonison (produced by Fusarium molds), and ochratoxin (produced by Penicillium molds). Deoxynivalenol (DON) is considered a key mycotoxin as other mycotoxins are seldom found in silages if DON is absent. Mycotoxin-producing molds are always present on crops in the field, so some mycotoxins are usually in crops at ensiling. As mold growth is spurred by wet field conditions, mycotoxins are more common in fall-harvested crops.

Cattle are less prone to mycotoxin toxicity than nonruminants because rumen bacteria can detoxify most mycotoxins. At-risk cattle include calves with limited rumen function; cows with suboptimal rumen bacterial populations, such as fresh cows with low intakes; cows with high ruminal passage rates, such as high-producing cows; and recently bred cows.

Visible mold on silages indicates that mycotoxins may be present. If you see molds, inform your nutritionist, who can take a sample of the suspect silage and have it analyzed. Transport samples to the laboratory quickly since mycotoxins can be produced in the presence of oxygen after sampling. While most mycotoxins listed above can be analyzed for, the assay costs may be high, although not as high as the costs of animal losses if toxicosis occurs.

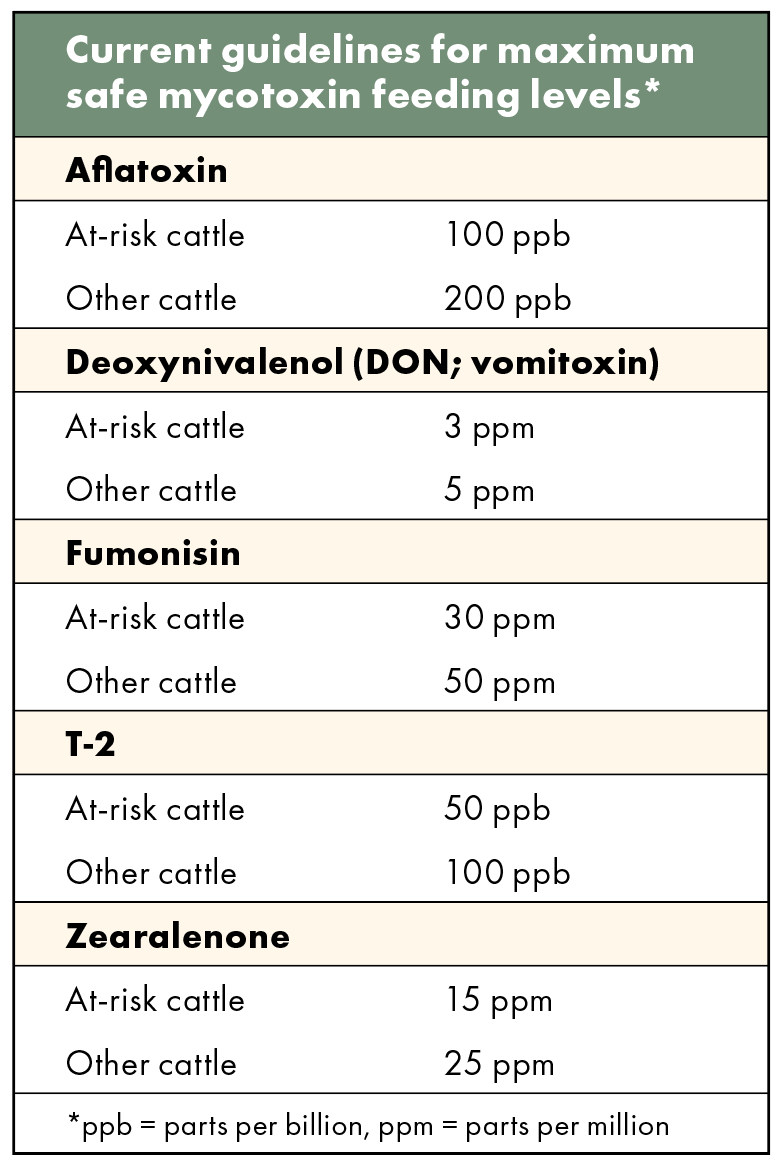

There are no totally safe dietary mycotoxin levels, but there are levels that are generally considered safe. In addition, not all mycotoxins have been investigated sufficiently to create “safe” levels. Current guidelines for common mycotoxins are listed in the table.

Practices that help

Ensiling will not detoxify mycotoxins, which are largely produced in the field, as they are very stable. However, ensiling will dramatically reduce mold activity, at least if oxygen is unavailable. Good silo unloading practices (for example, keeping flat silo faces, 6- to 12-inch daily face removal, and no leftover silage at day’s end) will help prevent molds from growing once oxygen is available at load out.

If dilution is impractical, some dairies have success feeding 100 to 200 grams per cow per day of sodium bentonite, a form of clay that binds to mycotoxins so that they are inactivated and pass harmlessly through the gastrointestinal tract. Bentonites originate from many sources and differ in unknown ways. They are unlikely to be equally effective against all mycotoxins. This may explain why some dairies have success with bentonite and some do not. There are also companies that market mycotoxin binders, which act similarly to bentonite but will be more consistent.

If high levels of more than one mycotoxin are in silage, then we enter uncharted waters, and the feeding guidelines may or may not be valid. In such cases, be conservative with the feeding guidelines. Remember, DON is considered a key mycotoxin to assay, as others are seldom found in silages if it is absent.

This article appeared in the January 2023 issue of Hay & Forage Grower on page 25.

Not a subscriber? Click to get the print magazine.