Although alfalfa weevils have developed resistance to pyrethroid insecticides, causing severe alfalfa losses in the Western U.S. and concern elsewhere, producers may still be able to utilize pyrethroids on a limited basis. They’ll need to alternate those insecticides with others using different modes of action as well as implement additional control options, according to Alfalfa Checkoff research by Kevin Wanner, Montana State University Extension entomologist.

The research also highlights the need to register new insecticides for alfalfa with different modes of action — critical for alfalfa weevil management, he noted.

In 2019, Western farmers and ranchers reported losing a majority of first cutting to alfalfa weevil defoliation after two or even three applications of pyrethroid insecticides. Weevil populations ballooned to high levels — 100 larvae per single sweep net sample, which is five times the economic threshold. “After talking to colleagues in other Western states, it was clear that alfalfa weevil resistance to pyrethroid insecticides was suspected across the region,” Wanner said.

The producer reports prompted a collaboration between Montana State University and the University of California–Davis to quantify the degree of pyrethroid resistance in the West and develop multi-state recommendations. That research led to Wanner’s Alfalfa Checkoff-funded project, which entailed on-farm research to support the registration of new insecticides for alfalfa.

“The majority of effective and available insecticides for alfalfa weevil control all contained pyrethroid active ingredients. It quickly became clear that forage alfalfa suffered from a lack of different active ingredients with different modes of action that can be used in rotation to manage pyrethroid resistance in alfalfa weevils,” Wanner asserted.

The purpose of the project was to evaluate new insecticides, combinations of older insecticides, and the timing and rates of currently registered insecticides for control of alfalfa weevil. “We were able to take advantage of a USDA-NIFA-funded research project to maximize the results of NAFA’s Alfalfa Checkoff grant,” Wanner noted. “Good on-farm collaborations with regional producers and implementing consistent experimental procedures in three diverse alfalfa-producing regions in Montana, Oregon/Washington, and Arizona proved to be a valuable approach.”

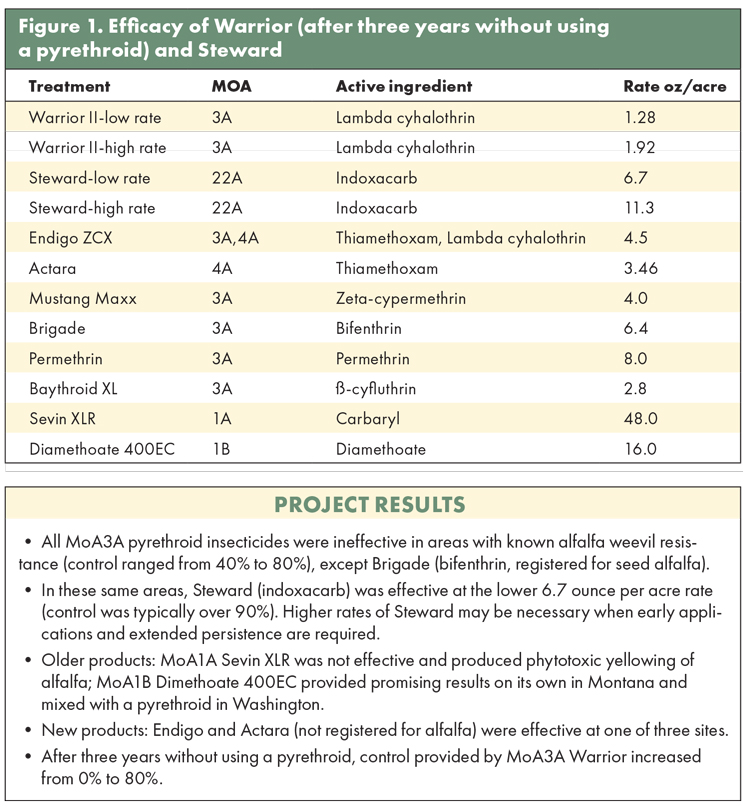

Wanner’s research showed, because of cross-resistance, all mode of action (MoA) 3A pyrethroid products registered for forage alfalfa become ineffective. Rotating the insecticide MoA and using noninsecticide strategies such as an early harvest, where applicable, are critical to preserving their usefulness.

“If you see ‘slipping’ control with pyrethroid insecticides — for example, needing maximum label rates to achieve the same level of control previously provided by lower rates — managing the resistance will prolong the usefulness of this valuable insecticide group,” Wanner said.

By conducting trials in the same commercial field in Montana for four consecutive years, Wanner and his team made a preliminary estimate of how quickly pyrethroid insecticides might regain their effectiveness. “Avoiding the use of pyrethroids for three to five years in areas with high resistance may restore their efficacy, but resistance will return quickly when pyrethroid use is resumed. I’d recommend using MoA3A pyrethroids no more than once every three years, rotating with MoA22A Steward and noninsecticide options,” Wanner pointed out.

“The diversity of alfalfa production systems and the importance of customizing alfalfa weevil management recommendations were reinforced by this project. A ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach will not work,” he said.

This article appeared in the February 2024 issue of Hay & Forage Grower on pages 12-13.

Not a subscriber? Click to get the print magazine.