While portions of the country are experiencing drought conditions, it seems like many others are faced with flooding problems. Though rain is usually a good thing when it comes to forage, too much can emerge in pastures and hayfields.

Christine Gelley, extension agriculture and natural resources educator at The Ohio State University, offered some options for managing flooded pastures in an Ohio Beef Cattle Letter article. The first order of business is to minimize mud. “One of the best ways to manage mud in grazing situations is to keep animals moving and give pastures rest,” explains Gelley. Splitting larger paddocks into small paddocks while rotating animals frequently and fencing out particularly wet areas will reduce damage to the stand. Frequent rotation will also better distribute manure, which helps prevent erosion. If seedheads develop during the rest period of the rotation, come back when the ground is dry and clip them. Clipping restimulates the plants and, in the case of tall fescue, lowers the risk of toxicity in the future. When taking equipment into the pasture, opt for smaller loads and use light implements with tires that have a large surface area. The next option is to ensure enough nutrients are available for optimum productivity. Having a legume stand of 20 percent or more in a pasture helps replace leached nitrogen and the need to replace it. Nitrogen leaves pastures through volitization, leaching, and harvest. Since there are no cattle to replace nitrogen in hayfields through urine and manure, these have a higher need for nitrogen than pastures. If applying dry urea or other forms of ammonium nitrogen, use a urease inhibitor such as Agrotain or apply the fertilizer prior to a predicted rain event. This can be done between the first and second cuttings. If wanting to stockpile forage for fall or winter grazing, a third application may also be needed. “The amount needed depends on yield goals, actual forage removal, spring fertilization, soil pH, and grass species,” Gelley explains. If a pasture experiences flood conditions, be aware that flowing water can deposit soil, weed seeds, manure, and microbes, which can have negative impacts on animal health. Digestive issues can arise if animals ingest silt when deposited levels are high. Weed seeds that are deposited in pastures can establish themselves in damaged areas and crowd out desirable forages. This can reduce intake of high-quality forages. If water flowed through an area that contained manure or sewage, microbes and parasites could also be an issue. To maintain herd health, wait one to two weeks before returning animals to pasture. Once the pasture has drained, look into other decisions that may reduce the likelihood of future flood events. “Consider reseeding heavily-damaged areas,” Gelley says. “Choose varieties that will withstand the conditions of your operation,” she adds. Gelley also suggests planting an annual forage as an emergency forage source in flooded areas that are damaged. Annual forages reduce further erosion, compete with weeds, and supply feed for animals faster than perennials. Annual ryegrass is one option due to its high tolerance to poorly drained soils. Wheat is also a good wet-soil crop, with oats, rye, and sorghum-sudangrass being fair options.

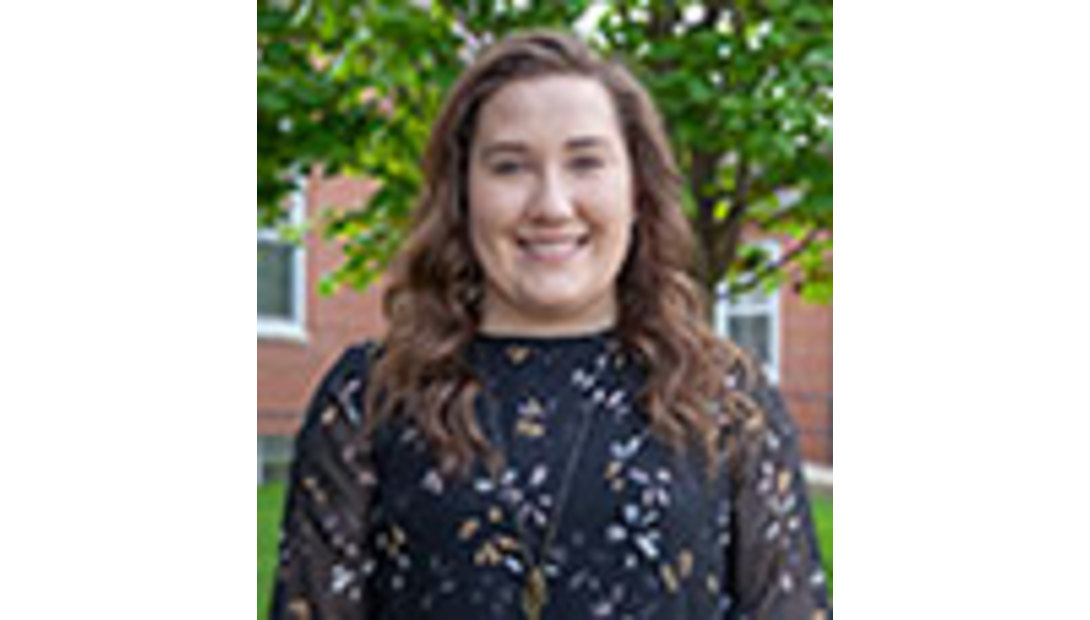

Kassidy Buse

Kassidy Buse is serving as the 2018 Hay & Forage Grower summer editorial intern. She is from Bridgewater, S.D., and recently graduated from Iowa State University with a degree in animal science. Buse will be attending the University of Nebraska-Lincoln to pursue a master’s degree in ruminant nutrition this fall.