It is common to hear from university faculty that stocker cattle and Kentucky 31 tall fescue are a bad combination due to the forage’s fungal endophyte and its impacts on animal performance. Indeed, there are 50 years of research data — and compelling pictures — supporting this claim. But what if we have been thinking about a stocker cattle business model in the Fescue Belt that is out of date?

The United States produced 33.6 million beef calves last year, which was the smallest calf crop since 1948. When there were ample calves to choose from, cattle buyers had leverage to be picky about size, type, and their management system. These buyers historically wanted 800- to 900-pound yearlings that were on pasture with minimal supplement to take advantage of a concept called compensatory gain, in which cattle gain weight at a faster rate than expected after a period when growth is below genetic potential. With beef demand expanding and calf crops shrinking, buyers no longer have that luxury.

I believe it is time to re-evaluate our mental model of stocker cattle production in the eastern United States. I have been conducting research for the past five years that suggests Kentucky 31 tall fescue can, in fact, be the forage base in a stocker cattle business.

Focus on the first half

In the 1970s, Clenton Owensby and Ed Smith were faculty members at Kansas State University who investigated stocker cattle production in the Flint Hills. The classic stocker production system in this region began when cattle were turned out to pasture around the first of May and lasted for six months. They observed that two-thirds of the weight gained by cattle occurred in the first half of the grazing season. Based on this observation, they began experimenting with “double stocking” pastures. In this system, twice the number of cattle were turned out on the same acreage for half the time.

This system was evaluated over a 10-year period in a research article published in 2018, which found that gain per head was 299 pounds for cattle that grazed pasture for six months and 199 pounds per head for cattle that grazed pasture for three months. However, due to having twice the number of cattle in the latter scenario, cattle weight gain per acre rose by 33% in the double-stock grazing system.

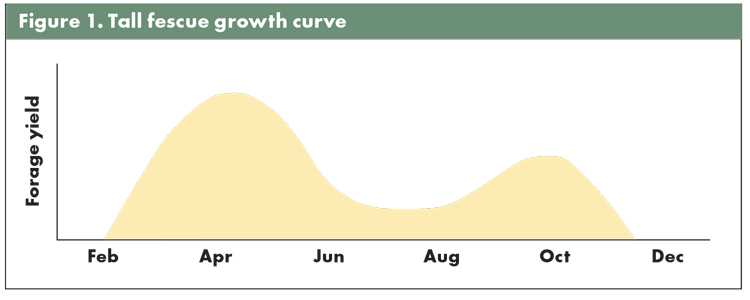

Tall fescue grows rapidly in the spring, but once a seedhead emerges, the plant goes dormant over the summer months. A six-month stocker system in the Fescue Belt requires cattle to graze forage during the summer slump. Therefore, implementing a double-stock grazing system may be an effective way to improve stocker cattle productivity.

More gain in less time

In our latest research project, we set out to test an 84-day double-stock system against a 168-day season-long system on Kentucky 31 tall fescue pastures. Across the pastures, 88% of fescue tillers sampled contained the toxic fungal endophyte, and we do not overseed clover, which is a strategy known to improve performance in forage systems anchored in Kentucky 31 tall fescue.

We turned out 500-pound heifers at rates of 2.4 head per acre for the double-stock system and 1.4 head per acre for the season-long system. Heifers in each group grazed the same pasture for the entire project. All heifers were turned out to graze on March 31, 2023, and pastures were fertilized with 40 pounds of nitrogen per acre earlier that month.

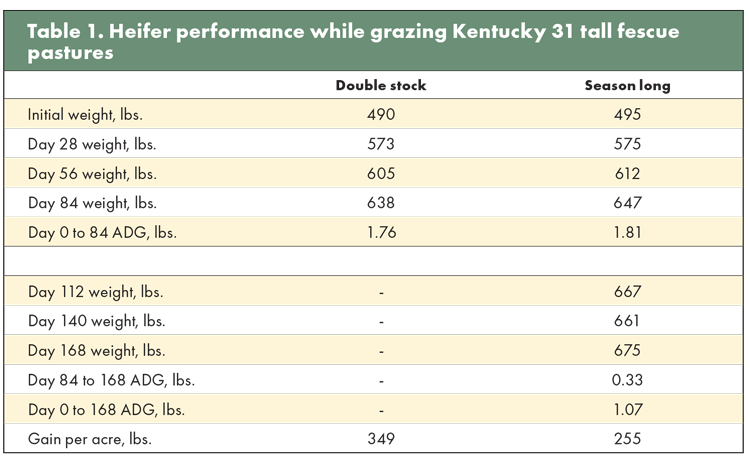

Table 1 contains the results of our project. After 84 days, heifers assigned to the double-stock system were weighed and removed from the project while heifers in the season-long system stayed on pasture for another 84 days. During the first 84 days, double-stocked heifers gained 1.76 pounds per day, whereas season-long heifers gained 1.81 pounds per day. Over the second half of the project, the season-long heifers only gained 0.33 pounds per day.

Overall, heifers assigned to the double-stock system gained 148 pounds per head while season-long heifers gained 152 pounds per head. On a gain per acre basis, pastures assigned to the double stock treatment had 349 pounds of body weight gained per acre and pastures that were grazed all season had 255 pounds of body weight gained per acre. The season-long heifers only gained 28 pounds in the latter 84 days of the project. The difference between the treatments is a function of stocking rate; we had more heifers on the double-stocked pastures.

Ongoing observations

My lab has only begun to scratch the surface of this concept. In 2024, we are testing a complementary forage, sunn hemp, to fill the summer slump forage gap for stockers. We are also going to evaluate the ability of feed supplements to improve weight gain of stockers while grazing.

Dilution has long been one solution to fescue toxicosis, but perhaps the best advice is to simply avoid grazing Kentucky 31 tall fescue during the summer months after forage has put a seedhead out and gone dormant. Rotating stockers to native warm-season grass pastures from mid-June to September is another option that we are interested in evaluating.

The big picture is that we must think about matching forage growth rate and cattle feed demand. When we create grazing systems that require conservative stocking rates to stretch forage supplies beyond the vegetative stage, we are giving up performance in the system. A successful stocker cattle business is highly dependent on weight gain. Kentucky 31 tall fescue pastures can provide that weight gain in the spring so long as cattle are removed from pastures after seedheads emerge and forage goes dormant.

This article appeared in the April/May 2024 issue of Hay & Forage Grower on pages 16-17.

Not a subscriber? Click to get the print magazine.