The cow-calf industry is set to see a few profitable years once again. The national beef cow inventory is at its lowest numbers in decades with USDA’s July 2023 count indicating a herd size 3% smaller than the previous year. The continued dry weather may have impacted the herd size, but based on the information from agricultural economists, it would seem herd expansion has not started at any significant pace.

The ranches and farms raising beef cows make decisions and investments into enterprises that are lower risk, and in most years, lower returning. Land ownership is a long-term investment with hope the land value improves over time. Yet, rising land values lead to higher taxes, which must be accounted for in the operation expenses.

Higher interest rates are also inflating operating costs for ranches and farms. A $50,000 loan paid over five years at an interest rate of 5% or 8% results in a $4,200 increase in interest paid. The cow-calf system must therefore be managed at a greater efficiency, balancing input costs with production responses.

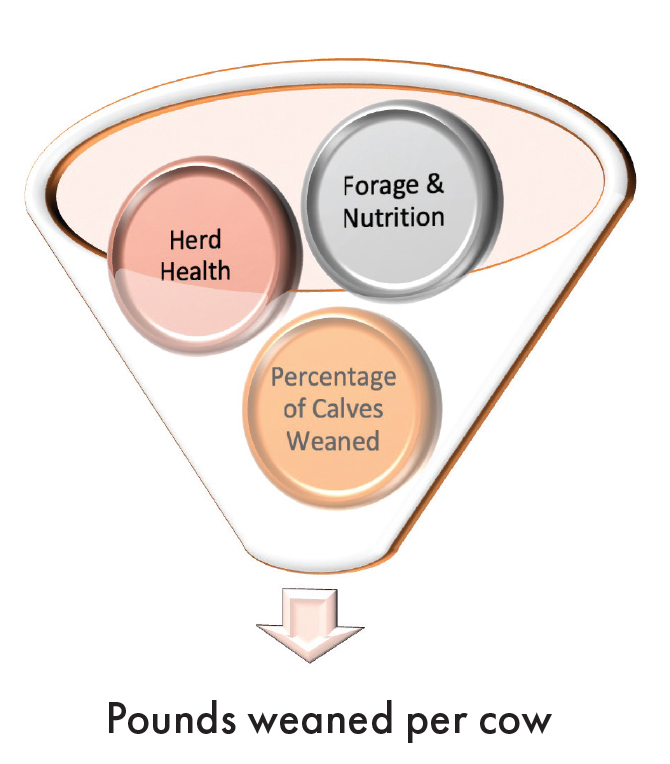

The Standardized Performance Analysis (SPA) data outlined the pounds of calf weaned per cow exposed was key for profitability in cow-calf systems. Many factors influence this production parameter.

Factors of profitability

The number of calves weaned and the actual weight at weaning are major overarching factors with each being impacted by several elements. Herd health has a direct impact on abortion losses, scours, and respiratory disease, all swaying both the number of calves weaned and their weight. Bull libido and fertility affect the number of cows that become pregnant, influencing the number of calves born and weaned. Are you managing everything at a function that provides a rate of return for the factors that impact the overall herd profitability?

Forage systems are foundational to this profitability index. Enhancing our beef production per unit of grazed and harvested forage is critical. Climate smart agriculture encompasses options such as rotational grazing, and preventing abortions and neonatal death losses through improved herd health lowers carbon dioxide and methane production by increasing pounds of calf weaned per cow exposed. Essentially, every factor that plays a role in promoting overall herd profitability with more pounds of calf weaned per cow exposed will directly lower the carbon footprint of the cow-calf system. Thus, it is a win-win situation.

Strive for a better system

Forage availability is the first place to start. Recent years of high fertilizer prices have likely led to limited or no investment in fertilizer for forage acreage used in beef cow-calf herds, particularly in the Midwest and Southeast. Correcting soil pH is the first step and the lowest investment to improve soil fertility and subsequent forage production. Bringing soil fertility into a range that supports legumes can assist in capturing atmospheric nitrogen for greater forage production and quality.

Stand assessment following drought conditions will be helpful to determine the potential stand viability and risk of weed encroachment. Previous research conducted by a colleague suggests every pound of weed dry matter growing in a field lowers desirable forage production by a pound. Drought conditions often result in overgrazing of already stressed plants, reducing desirable forages.

As forage production is reduced from either summer dormancy or overgrazing, the maintenance energy expended by the beef cow goes up. Research has demonstrated lowering the plane of nutrition available to beef cows reduces milk production, which will directly lower calf weaning weight. Additionally, suckling calves rely on available forage to meet their nutritional needs for growth at an ever-increasing rate after 2 months of age. The normal lactation curve leads to reduced milk production after six to nine weeks, although calves require greater nutrients to support their body weight gain and genetic potential for growth.

Take soil samples to assess soil fertility and make plans to improve stands after determining nutrient losses in the pasture after drought conditions. Ensure soil fertility will promote the establishment of the forage species being considered. As an example, annual lespedeza does better on marginal soil fertility than red and white clover. Though lower yielding, annual lespedeza can be another forage option that is less common than it was a few decades ago.

Consider new seedings

Are stands in poor shape? Is renovation inevitable? Thin Kentucky-31 endophyte-infected tall fescue pastures could be candidates for upgrading to novel-endophyte varieties. Novel endophytes provide plants with persistence while lowering or eliminating the production of detrimental alkaloids that impact animal performance.

Arkansas research revealed the conversion of 25% of pasture to novel-endophyte tall fescue can benefit cow-calf systems. Seeding bermudagrass varieties that are cold tolerant, or native forages, are other options to consider. Conversion of limited acreage to a warm-season species can provide forage when cool-season forages are dormant or less productive.

Now is a good time to assess soil fertility and stand composition to develop a plan for improving your forage system. A variety of tools are available to help enhance your pastures and boost the pounds of calf weaned per cow exposed. These improvements can be implemented stepwise and do not require an all-in approach. Using different approaches, especially when considering new forage species, provides the opportunity to evaluate these changes under your management.

This article appeared in the February 2024 issue of Hay & Forage Grower on pages 14-15.

Not a subscriber? Click to get the print magazine.