One chance per year. That’s all you get. There are no do-overs — no country club mulligans.

That one chance refers to the proper timing of making first-cut alfalfa, and given the price of other commodities, the stakes are at an all-time high this year.

No other cutting of alfalfa offers more opportunity than the first one. Forget the myth that big stems equal poor quality; it’s simply not true. In the vast majority of years, the first cutting of alfalfa offers the opportunity to harvest the highest concentration of digestible fiber of any remaining summer cutting. If the current cool spring continues, fiber digestibility should be well above average with a timely harvest.

During the past 15 years, the University of Wisconsin Department of Extension has coordinated the Wisconsin Yield and Persistence Project. Yield and forage quality have been measured on 127 different production fields over a stand’s full productive life. In other words, a lot of data.

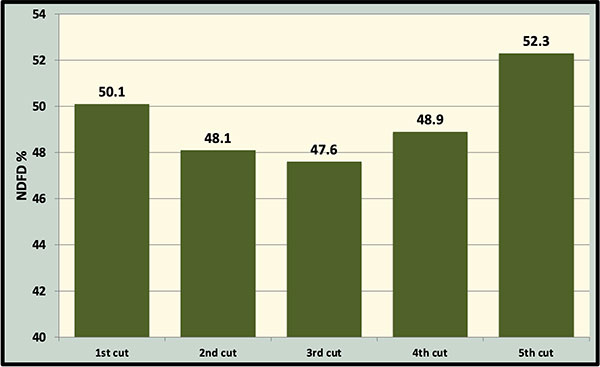

The average neutral detergent fiber digestibility (NDFD) of first cutting topped that of subsequent cuttings except for the low-yielding fifth cuts that were often taken in late fall (see graph). That same first-cut forage accounted for 38% of the total-season yield in a typical four-cut system.

NDFD by cutting in the Wisconsin Yield and Persistence Project (2007-2021)

Even small improvements in fiber digestibility can make for large differences in livestock performance; however, fiber digestibility usually takes a wild ride during the course of spring forage growth.

Although first cutting offers the opportunity for harvesting forage with the highest digestible fiber of the growing season, forage quality declines at a faster rate for first cut compared to subsequent cuttings. This presents the possibility of also harvesting large quantities of very poor, low-digestible forage once maturity advances beyond alfalfa bud stages.

First cutting is the only one of the year when there is no number of days since the previous harvest. The decision options are wide open, but the consequences of the decision often impact the rest of the harvest and feeding seasons.

Given the high stakes, the need to estimate first-cut forage quality as it stands in the field becomes a necessity if forage quality train wrecks are to be avoided. Attempts to gauge forage quality solely by either maturity stage or calendar date have proved inconsistent at best, or a total failure at worst. Spring growing conditions are simply too variable.

Predictive equations for alfalfa quality (PEAQ), growing degree day tracking, or clipping fresh forage for analysis are useful tools for estimating first-cut forage quality. Investing time in these forecasting methods can help take some of the guesswork out of the process.

Weather matters

The downhill ride in first-cut forage quality is accelerated by warming temperatures and becomes more dramatic if grass is present in the stand. Missing the optimum time to harvest first cutting is akin to missing Christmas and getting a lump of coal on New Year’s Day in the form of many tons of low-quality forage.

No cutting experiences the possible range in environmental conditions that first cutting does. It can be cool and wet, cool and dry, hot and wet, or hot and dry. This potential range in growing environment has a profound impact on forage growth, nutritive quality, and optimum harvest date from year-to-year.

In addition to forage quality, first cutting also has some unique yield characteristics. As mentioned previously, spring alfalfa growth almost always provides the highest percentage of total-season dry matter yield. The economic consequences of making a first-cut timing mistake are higher than for any other cutting because there is usually more forage than any other cutting.

Similar to forage quality, changes in initial spring growth occur more rapidly for yield than for summer and fall growth cycles. Growing environment will dictate the rate of dry matter accumulation per acre, which can approach 100 pounds per acre per day.

First-cut timing sets the pace for the rest of the growing season. In other words, the first-cut harvest date may dictate how many future cuttings will be taken, the interval between those cuttings, and/or how late into the fall the last cutting will be harvested.

The challenge is defined. The stakes are high, and as I’m often told, don’t blow it.