Many Montana livestock producers winter-graze mid- to late gestation cattle on dormant alfalfa fields to make use of the protein- and energy-rich forage. But some have questioned whether grazing adversely affects alfalfa persistence and production the following year, said Megan Van Emon, Montana State University (MSU) Extension beef cattle specialist.

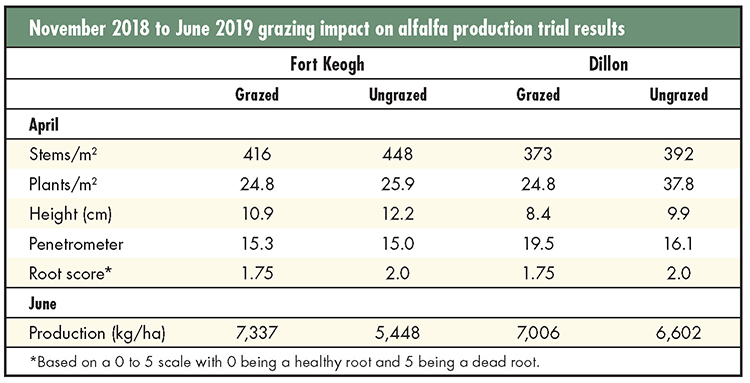

The following April, grazed fields and ungrazed areas next to them were evaluated. Soil penetrometer readings to measure compaction, plant height, stem and plant density, and root scores were taken. Before the June 2019 first alfalfa harvest, plant biomass and height samples were collected, weighed, and dried at 60°F to estimate dry matter production.

“We didn’t see any negative impacts,” Van Emon said. “As long as you graze within reason and don’t let those plants get too short, they still have some aboveground plant material for optimal growth next spring.”

Project result

No negative impacts of winter grazing were observed on subsequent-year alfalfa production.

In Montana, two to three cuttings are usually taken during the growing season, in part because of a lack of moisture. Once the high-quality forage goes dormant, grazing its fields can add gains on cattle held over the winter and provide feed when supplies are limited, she said.

“Montana is slowly creeping into a larger drought area,” Van Emon added. “We have had pretty decent moisture for most of the summer, but it’s smoky and hazy here now because of our wildfires. As the forages dry up, producers are looking for an alternative grazing area, and alfalfa is a huge benefit to those producers who are maybe lacking pasture availability.”

In her research, Van Emon found little difference when comparing grazed to ungrazed field areas. But she did note one distinction. “It was interesting. If you look at June production, it wasn’t statistically different, but we did see some numerically increased production from the grazed versus the ungrazed areas.” She noted that the ungrazed areas were small in size but thought they would be more similar in production to the grazed fields.

Van Emon explained that producers also wanted to be assured their cattle would perform well on the higher quality forage. “They wanted to make sure those cattle didn’t go backwards once they got on that alfalfa, which we did not expect, and we did not see,” she said. Cattle were weighed before going into fields and after they were taken off. “The cattle all looked really good, but I think that’s an area we could pursue in the future — taking regular weights during the grazing of the alfalfa,” she added.

To view the project’s final report, visit: https://www.alfalfa.org.