Glenn Shewmaker, extension forage specialist at the University of Idaho, reported that dry hay losses during storage are attributed to harvested forage moisture, weathering, climate and heating. In a presentation at the Western Alfalfa & Forage Symposium in Reno, Nev., Shewmaker shared some of his research results along with a review of other studies focusing on stored hay quality losses.

Though hay storage losses often can't totally be avoided, there is no arguing that good storage management can keep losses to a minimum. Said Shewmaker, "The more valuable the hay, the easier it is to justify spending time and money to improve storage conditions. If barn or shed storage is not available, make your stacks in a sunny, breezy location, on an elevated pad of rock, and cover them with tarps." He further noted that hay storage losses are not easy to recognize because they are difficult to accurately measure.

Forage moisture:

"Hay with less than 15 percent moisture is relatively stable with minimal respiration losses," said Shewmaker. He pointed to research showing that storage dry matter losses average 3 percent of harvested dry matter weight for indoor storage and 14 percent for outdoor storage. Initial forage moisture plays a large role in the extent of dry matter losses, which can easily exceed 10 percent when hay is baled in excess of 15 percent moisture and stored outside.

High-moisture hay is also subject to mold growth and greater microbial respiration. This results in additional dry matter losses that may extend throughout the storage period. Shewmaker suggested that visible mold development for small square bales is likely to occur when moisture exceeds 20 percent. Large round or rectangular bales will develop mold at moisture levels over 18 percent, and large rectangular bales (one-half to 1 ton) should be baled below 16 percent moisture if no preservative is used and dry matter losses are to be minimized.

Weather:

Dry matter and forage quality losses for hay that is stored outside on soil without being covered are significant. The outer 2 to 3 inches of the bale may increase in moisture by as much as 120 percent. Once wetted, a bale does not easily shed water. Shewmaker noted that a 1-inch rainfall adds about 20 gallons of water to a 4-foot by 8-foot bale surface. The wetted interface deepens with each subsequent precipitation event; this causes dry matter and forage quality losses to far exceed normal and expected levels. Frequent precipitation is more damaging than the same amount of precipitation coming all at once.

"Weathering can also occur from the ground," said Shewmaker. "Dry hay touching damp soil or concrete draws moisture into the bale, and we sometimes see up to 50 percent of the total dry matter loss in storage coming from the bottom bales." The forage specialist cited research that found only 87 percent of the digestible dry matter is conserved when stacked outside, uncovered and on the ground compared to barn storage. Conversely, hay that was covered with plastic on a raised surface conserved 97 percent compared to barn storage.

Climate:

Climatic conditions during storage can impact dry matter and forage quality losses. High humidity slows drying of stacked wet hay. Warm temperatures, coupled with humid and overcast conditions, raise the odds for microbial growth in hay. Cold, arid, and sunny conditions tend to retard microbial growth. Well-ventilated conditions are also conducive to hay drying and reduce the likelihood of excessive heating.

Heating:

Though dry hay stored under cover is relatively stable, minor heating still results in dry matter losses of about 5 percent over a six-month storage period. When hay is either baled at higher moistures or wetted during storage, forage quality losses from respiration and heating begin to mount. Respiration results in lower forage quality by reducing the amount of nonfiber carbohydrates (sugars and starch). This increases the percent of fiber fractions and may actually cause crude protein levels to increase. Excessive heating causes usable protein to decrease as amino acids and sugars bind to form insoluble nitrogen forms. This is often referred to as caramelized forage.

Idaho research:

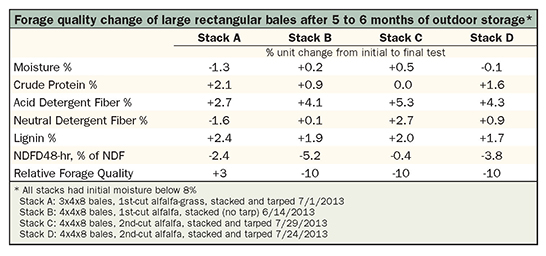

Shewmaker shared some initial results from his research where four different stacks of hay were tested immediately following harvest and then one month and five to six months after initial storage. Even though the initial moisture of all the stacks was below 8 percent and conditions during the storage period were relatively dry, degradation in forage quality occurred in almost all cases. Some of the results are presented in the table below.