The hay market on the West Coast is unique compared to much of the United States. In 2017, 2.6 million metric tons (MT) of alfalfa hay and 956,000 MT of timothy hay were exported from West Coast ports, according to the USDA’s Foreign Agricultural Service.

A majority of these exports head to Japan, China, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, South Korea, or Taiwan to be used by dairies, racetracks, pet food companies, and more. With Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and California’s close proximity to the Pacific Ocean, the export industry is a large and important asset for the hay industry in the West.

Within 100 miles of our farm in Moses Lake, Wash., there are over 15 hay exporters in the state of Washington alone. A majority of these exporters simply process hay they buy from their client base of growers while others also supplement their hay inventory by running their own hay operation. These types of operations will sometimes rent land to grow their crops, will approach a grower and offer them money for a standing crop, or purchase the crop after the grower puts it in a windrow.

Buying a crop from a grower before it is put in the bale can mitigate some of the stress and costs the grower faces when attempting to put up a high-quality crop, but it often comes at a lower purchase price. The exporter incurs the risk of weather damage before they get the crop into a bale and hauled to their facility.

Exporters generally don’t want to incur too much risk because this has the potential to elevate costs and their product can be more difficult to market if, for example, it receives rain damage. Once the hay is purchased, everything is turned over to the exporters for the completion of the shipping process.

It’s a relationship business

Exporters work off of building both relationships with their growers, as well as their client base of overseas customers. Both relationships are of vital importance to the success of an export operation. The process generally begins with a buyer identifying the need of one of his customers, a price point of what they are wanting to pay for a product, and what growers may have the type and quality of product that they need.

Next, buyers come and assess the product, pulling hay samples and using a grading sheet to send to their customer for approval. The samples are sent off for a lab analysis to determine nutrient and feed value. If the customer likes what they see, they give the go ahead for the buyer to talk to the grower about purchasing the crop. Most of the business conducted between the buyer and their customers overseas is on the phone or through emails to finalize the deal and determine a price for the product.

Package size differs

The negotiations between the buyer and the grower are generally pretty straightforward. As a grower, we rely and trust the grading by the buyer and the price they are offering for our crop. We generally have a good idea of where the market is at and what we can get for our hay. Once the buyer and grower agree on a price, a contract is made that documents the price per ton, haul-out dates, and the amount of money to be paid up front if the hay has to stay on the farm for an extended period.

When the hay is eventually hauled from the field to the processing facility, it is pressed into the type of package that the end customer is searching for. Pressed packages can range from something called a “mag” bale with multiple cuts weighing between 900 and 1,000 pounds to double compressed half-cut bales weighing between 55 and 60 pounds. The processor then handles the logistics for the shipment to ensure timely arrival of their product to their overseas customer.

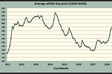

Currently, growers, exporters, and some of their clients are all wondering how the tariffs imposed on China are going to affect the export market.

Is it going to cause less demand and/or lower prices for forage products from the West Coast?

No one can say for sure what is going to happen, but the impact could definitely have a trickle-down effect in the market in the upcoming months. Stay tuned. •

This article appeared in the August/September 2018 issue of Hay & Forage Grower on page 22.

Not a subscriber? Click to get the print magazine