It’s no secret that corn silage has changed over the years. It has not only evolved from a feedstuff used primarily for heifers and dry cows to a major and key component of milking cow rations, but it has seen change in how it is produced and processed.

Randy Shaver, extension dairy specialist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, reflected on the past, present, and future of corn silage production during the recent World Dairy Expo held in Madison, Wis., last week.

The past

Thirty to 35 years ago, corn silage was averaging about 50 percent neutral detergent fiber (NDF). When it came to lab analysis, there were no commercial lab assays available to determine starch content or in vitro NDF digestibility (ivNDFD).

The corn hybrids and production practices available at that time gave much lower grain yields, which led to a high NDF and low starch concentration.

“The only corn hybrid selection programs available were for corn grain, which focused on bushel yields per acre and test weights,” Shaver said.

In those days, at least in Wisconsin, it was a common practice to chop the worst of your fields to become feed for heifers and dry cows.

“In the Midwest, if silage was to be fed to milking cows, it was only included at up to 25 percent of the forage in the ration,” Shaver explained.

Producers tended to chop their corn silage very fine; down to a quarter or three-eighths of an inch. This fine processing would break up the kernels and cobs so there was no concern about kernel processing or even effective fiber since plenty of haycrop silage or hay was still being included in the ration then.

Since the most common method of storage at the time was the tower silo, a dry matter content of 40 percent or greater was desired for less seepage and to prevent freezing in the winter. Microbial inoculant use was next to none.

Today

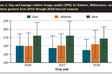

Fast forward to the present, and you will find that corn silage regularly features an average of 41 percent NDF, 54 percent ivNDFD, and 32 percent starch. Along with the availability of commercial starch content and ivNDFD assays, undigestible NDF assays can also be determined.

Hybrid selection is currently a key component in silage production. “Selection programs now consider starch content, some measure of the digestibility of the fiber, and include an index that ranks hybrids based on their quality,” Shaver explained.

With brown midrib (BMR) hybrids and others designed specifically for silage, producers can now make a selection to best fit their needs and goals.

Thanks to advancements in research and technology, kernel processing has become a staple in the silage production process. A longer theoretical length of cut (TLOC) to get more effective fiber out of silage has also been adopted.

As previously stated, kernel processing was never a concern in the past. Conventionally, a 20 percent roll speed differential was used with a TLOC of 17 to 22 millimeters. The more contemporary measures consists of a 40 to 50 percent roll speed differential and 17 to 26 millimeters for TLOC.

To top it off, the average dry matter content of silage is now around 35 percent as the silage is commonly stored horizontally in bunker silos or drive-over piles.

The future

So, what lies ahead for the future of corn silage?

Right now, the key measures of quality are the proportion of grain to stover and starch versus NDF concentrations. Silage NDF and starch concentrations of 36 to 40 percent and 32 to 39 percent, respectively, are now the norm for high-quality corn silage for high-producing cows. We are seeing, however, more sample analyses from dairy farms in the Upper Midwest coming back with only about 30 percent NDF and up to 45 percent starch or more. It can be quite a challenge to formulate healthy dairy cattle diets if this sort of silage comprises a high proportion of the forage dry matter being fed.

“We need to ask the question, ‘Do we want this type of corn silage analysis to become more of the norm in the future as grain yields continue to increase?’” Shaver posed.

In terms of fiber digestibility, the primary focus has been on lignin as a component of NDF with the hybrid effect, environmental differences, and hybrid-environment interactions regionally.

“I think this is a fundamental area that will continue to grow moving forward with not only comparing hybrids to each other but how they compare across different environments and management practices,” Shaver commented.

Kassidy Buse was the 2018 Hay & Forage Grower summer editorial intern. She is from Bridgewater, S.D., and recently graduated from Iowa State University with a degree in animal science. Buse is currently attending the University of Nebraska-Lincoln pursuing a master’s degree in ruminant nutrition.