It's flashy to be in the major leagues. On dairies, the lactating cows are the big leagues, with most forage programs focused on producing highly digestible forages for this group. Nutritionists center their attention on stats like dry matter intake (DMI), undigested neutral detergent fiber (uNDF), and NDF digestibility at 30 hours (NDFD30). Manure is screened and corn silage is dissected, floated, and measured with an electronic caliper.

Every great major league baseball team relies on their minor league affiliates to provide new talent year after year. The same is true for most top-notch dairy farms. A good forage program is needed to help make it happen. Let’s take a little trip down to the minors to scout the teams and consider some of the forage decisions that need to be made.

The Money Eaters

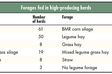

Double A ball on dairies might be comparable to the heifer program. While particularly important for generating new players for the big leagues, heifers utilize resources while generating no income. Heifers can consume a large amount of forage. It’s easy to forget that a 1,200-pound heifer can eat 25 pounds of forage per day (dry matter), not far from the 30 pounds of forage consumed by the lactating cow. For many dairies, the heifer operation may account for 20% to 35% of their forage needs, depending on the size of the heifer operation.

Over the years, the best dairy farms have made high-quality forages the backbone of their success. Prebreeding heifers thrived on high-quality haylage and some corn silage. Postbreeding heifers can be the challenge. These heifers do not need the caloric intake younger heifers do and can easily become overconditioned if the forage quality is too high. For this group, bulky, low-energy forages are in demand. Traditionally, they received the forage that was harvested late or was rained on. As dairies have become better at harvesting forage, sufficient inventories of low-energy forages often become an issue.

For the breeding heifers, three options might be considered. First, limit feed heifers to reduce caloric intake on high-quality feed. For most folks with crowded heifer facilities (yes, the Double A team is almost always crowded with less than perfect facilities), this likely is not a viable option due to limited bunk space. Second, cut the high-quality forage with a very low-quality ingredient like straw, oat hulls, or corn stubble. While this can work, you need to have a place to store this cutter and the ability to handle it correctly (access to tub grinder).

The third option is planning to harvest a forage designed for these heifers. Calling this a low-quality forage implies there is something wrong with it. That’s not the case. Think of it as a designated hitter . . . a forage with a purpose.

A team meeting with the nutritionist and agronomist is a must. Discuss the options for your growing conditions. They might include a winter cereal like rye, a warm season sorghum-sudangrass, an earless tropical corn silage, or maybe an alternative forage that’s aerial seeded into standing corn.

Near to the bigs

Triple A ball on dairies points to the dry cow and prefresh programs. These animals are about to make the big splash and represent about 12% to 18% of the lactating herd. Far-off dry cows (about 50% of the group) have similar nutritional needs to the growing heifers with an emphasis on keeping the energy levels moderate. Prefresh cows are perhaps the most difficult group to target with forages because of the limited size of the group and their specific nutrient requirements.

In the last 20 years, feeding prefresh cows has advanced immensely. We know that keeping energy levels lower with a bulky forage like grass hay or straw keeps the liver functioning better and reduces the rate of ketosis and displaced abomasums in fresh cows. At the same time, we are using nutritional strategies to impact calcium (Ca) metabolism to reduce milk fever and, perhaps more importantly, subclinical hypocalcemia. Cows that transition with a healthy liver and proper calcium metabolism simply take off better after they calve.

There are three strategies that can be attempted to meet these needs. First, very bulky forages with low Ca and potassium (K) levels; for most farms, this can be difficult to attain and is seldom attempted. Fertilization and manure makes this unlikely on most farms.

Second, using a binder in the ration to tie up Ca (lowering Ca available to the cow) can allow some haylage.

to be utilized in the diet along with some corn silage and straw. The research and practical farm experience is still developing on this front. Third, the most typical approach is feeding a diet of corn silage and straw or grass hay. The energy from the corn silage is cut with the straw/hay while keeping the potassium low for Ca metabolism (with the addition of a diet acidifier).

The straw and grass hay portion of this prefresh diet has caused many nutritionists to suffer from headaches and sleepless nights. Straw in the prefresh diet is typically fed at 5 to 10 pounds while grass hay will be fed at an even higher rate.

The need for straw and grass hay provides a big opportunity for forage growers. For many dairies, accessing this straw or grass hay can be difficult. There are a few major requirements for this forage:

1. The forage needs to be tested with a wet lab analysis for macrominerals. A standard near infrared reflectance spectroscopy (NIRS) forage quality analysis is not sufficient.

2. Particle size is critical to eliminate sorting. Processing straw and hay on the farm is not always an option. Using the TMR mixer as a bale processor is time consuming and inefficient. Producers will pay more for precut baled hay and straw.

3. The forage needs to be clean, free of mold, and protected from the rain. Prefresh cows sometimes have a compromised immune system, and reducing the potential impact of mycotoxins and molds is necessary for a smooth transition.

Finally, for those that grow forages, there can be an additional revenue stream. In areas of the U.S. where feedlot and dairy overlap, there are custom operators who grind hay and straw monthly for customers, eliminating the expense of owning their own tub grinder. In geographies with mostly dairy farms, I have seen a gap that presents an opportunity. Purchasing a high-capacity tub grinder with a little marketing might be a successful enterprise.

A dairy’s minor league farm system is crucial to the future profitability of the business. To help ensure success, design forage production and feeding programs to meet the specific needs of these “players” as they work their way up to the big leagues.

This article appeared in the January 2021 issue of Hay & Forage Grower on pages 30 and 31.

Not a subscriber? Click to get the print magazine