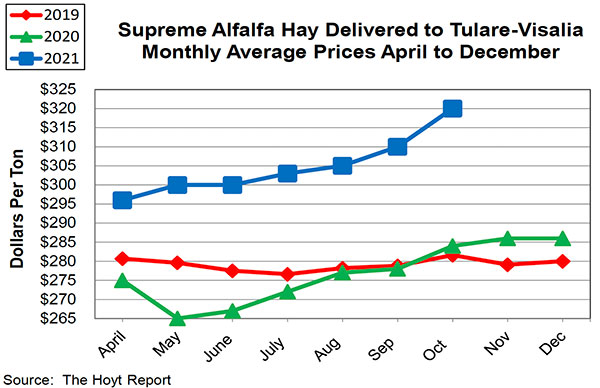

It was a trifecta of market movers that drove hay prices to record levels in 2021.

That trio of factors included drought, economic fallout from the COVID-19 lockdown, and a significant commodity price rally, according to Josh Callen who spoke at last week’s Western Alfalfa & Forage Symposium in Reno, Nev.

In evaluating the situation in California this year, the author of The Hoyt Report noted that many dairy operators in the Central Valley were resistant to pay high prices for hay. “Another thing that happened was extremely strong local markets in Idaho and Utah, which deterred growers in those states from shipping to California,” Callen said. “Lately, as winter approaches, we’re starting to see more purchases by California dairies for out-of-state hay. In some cases, I’m seeing prices in the $350 per ton range,” he added.

Although the price spread for Supreme hay is usually $80 to $100 between California and Idaho, this year it’s only been about $20 to $30, according to Callen who is based in Twin Falls, Idaho. “Lower quality hay in Idaho is up almost $100 per ton over the previous year,” he said. “That’s being driven by the beef ranchers who have run out of range grass to graze.”

Dryland timothy production in the Northwest during 2021 set record low yields, which was in sharp contrast to the previous year when record high yields were achieved. “The three-tie bales were about the same price as last year, but big bales were up quite a bit,” Callen said. “The retail timothy market has remained strong.”

The analyst also noted that the retail market for alfalfa has just recently shot up in the Imperial Valley of California. Buyers are now paying over $260 per ton for Premium quality hay destined for retail markets.

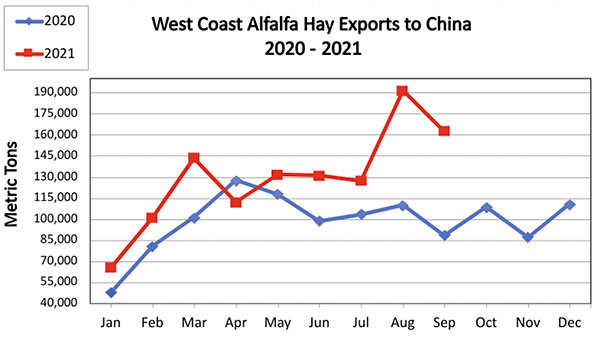

Hay exports

“The shipping situation is terrible,” Callen said. “It’s going to take time for this to sort itself out, but hay exporters are doing a pretty good job of working through this as hay exports are actually up 4% through September, which has largely been driven by China.”

Alfalfa demand from China has been high in 2021. “China is continuing to grow its dairy herd and making purchases of heifers out of Australia and New Zealand,” Callen said. “They need U.S. alfalfa, and the trade relationship has improved.”

In contrast to China, hay exports to the Middle East have dropped considerably. “They’ve really turned to Spain,” Callen noted.

Looking ahead

Callen said it’s difficult to know what is going to happen going forward. “There’s just a lot of economic uncertainty as it relates to inflation, interest rates, logistics, and spending.”

The analyst said that drought will have a big impact on hay markets going forward, especially in California. Recently, water conditions have improved in the Pacific Northwest.

Cow-calf producers are culling their herds and this will influence hay demand moving forward. A recent Farm Bureau survey of its members in the West showed that the average producer culled their herd by 30%, Callen noted.

“Given the current production situation in 2021, I don’t see hay prices changing too much, at least through spring,” he said. “I think there will continue to be resistance to buying on the dairy side, so I also don’t see a huge increase in price from where we are now.”

Callen noted that higher crop input prices, including water, will significantly raise what it costs to produce hay. The fertilizer price index is currently higher than it’s ever been. “Growers are going to be reluctant to give too much on their asking price simply because it costs so much more to produce product,” he said.