The abundant rain and snowfall in the West put a temporary Band-Aid on many areas that were either devoid of moisture or had their irrigation spigots shut off. A lot of hay growers in the region have renewed hope for a decent crop — at least for this year — and it’s been a long time coming.

Unfortunately, the beginning of the growing season has been a mixed bag for hay growers in other regions. From the Plains to New England, the usually abundant spring and early summer rains have largely been a no-show. These are mostly areas where backup irrigation isn’t an option.

On the positive side, it was an absolutely great situation for getting first-cut hay made. Making dry, first-cutting baled hay is often only a dream in the Midwest and Northeast. This year, balers rolled without delay. Rain was a nonfactor in most areas, which helped ensure timely harvests.

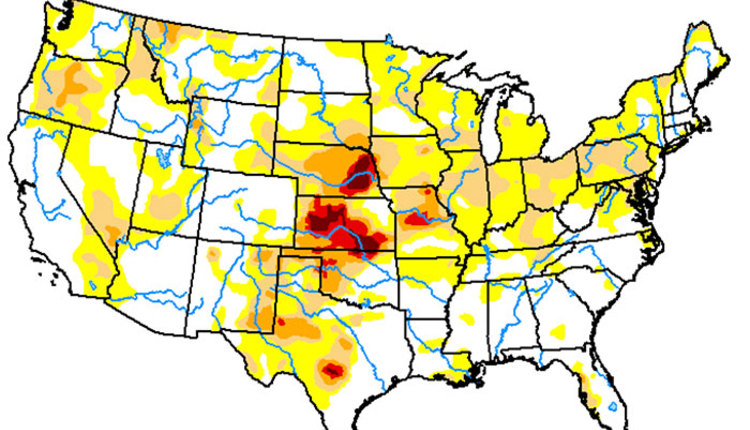

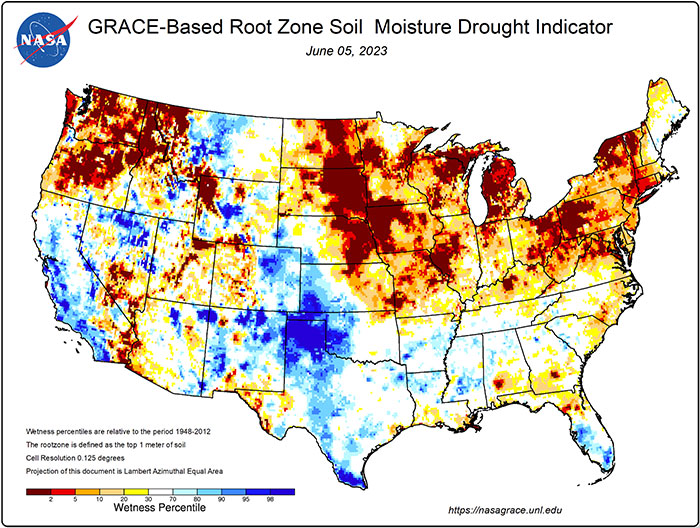

Despite the joy of not cursing the weatherman, a look at the root zone soil moisture map below tells a grim story for many fertile U.S. crop production regions that normally are colored some shade of blue during this time of year.

Annual grain crops can be hurt by short-term dry weather, but they also have the ability for compensatory growth when rains return. In fact, an early dry period often enhances corn yields because root systems strive to grow deeper and are better prepared for the hotter and drier summer to come. This, of course, assumes rain returns before too long.

Forage crops, on the other hand, suffer in times of drought, especially our cool-season grasses and legumes. Yield losses occur during even short stretches of dryness and that production is forever lost in the dust. There are no second chances for hayfields and pastures, only the hope for precipitation and a return to normal production in the near future.

I saw this brutal truth play out time and time again while monitoring alfalfa yields during my extension agent days. Although the impacted cutting number was different from year to year, two weeks of dry weather would absolutely hammer the subsequent harvest’s yield and maybe the next. Essentially, each period between cuttings was a new growing season. This was a far different scenario than what played out for the annual row crops that could make up for lost production in the subsequent good times.

A dry July

All is not lost just yet. It’s still early; however, should the current dry weather pattern persist, it’s not too early to be formulating Plans B and C. Those plans will look different depending on individual situations and current forage inventories. Some areas are heading into their second year of drought with minimal on-farm stocks while others may be coming off several good years with ample forage supplies.

For most dairies, a significant alfalfa yield decline this year would likely mean feeding more corn silage or feeding down existing alfalfa inventories. If those inventories don’t exist, or you feel the corn silage crop will also be threatened, purchasing additional standing alfalfa or corn from neighbors may be the best approach.

If acres are available for planting either now or later this summer, then planting warm-season summer annuals like sorghum species or an August-planted oat crop can bolster forage supplies.

For farmers relying on pasture or rangeland as their primary forage resource, warm-season summer annuals, higher culling rates, drylotting, feed supplementation, and early weaning are all components of the drought battle plan.

I recall visiting with two cow-calf beef producers a couple of years ago who noted that they adopted a baleage system to avert a future situation like they found themselves in following the droughts of 2011 and 2012. Their current drought plans essentially came down to this: Use stored feed from the good times to supplement during the bad times. Stored baleage was always Plan B.

Many of you have attended presentations where haymaking is villainized because of its cost compared to grazing. There’s little arguing this point, but making hay out of excess spring forage or from designated fields too far away to graze offers some reasonably cheap drought insurance when one considers the long-term cost of overgrazing pastures or selling cows when there is no other alternative.

Of course, hay can be purchased, but drought also sends the price of hay soaring and supplies in the opposite direction. Even if the current situation breaks this week, hay inventories have already been impacted, even if forage quality has not.

Some areas are better off

Many areas in the West and the Plains are getting moisture this year after several years of drought. Climatologists tell us that an El Niño weather pattern is beginning to set in. Matt Makens of Makens Weather LLC said this will spell some welcome relief for the Lower and Central Plains. Overall, he sees things setting up as follows:

Long-term weather is difficult to predict and local conditions may vary from your regional weather characterization. That said, 2023 is looking decisively different than 2022. Bottom line: Plan for the worst and hope for the best.