Forage research from universities and seed companies fuels advancements in the alfalfa industry. This research also lays the foundation for many producer recommendations, but scientific experiments don’t always reflect the reality of day-to-day operations or account for unexpected circumstances that can occur in a growing season. That is where on-farm data becomes valuable.

It is not uncommon for on-farm crop yields to be lower than those in research trials, but Nicole Tautges with the Michael Fields Agricultural Institute (MFAI) in East Troy, Wis., noted this yield drag is more significant for alfalfa than most other crop species. Alfalfa yields can also drastically vary from farm to farm, which raises questions about how much influence specific practices and soil conditions can have on forage production.

To answer these questions, Tautges, an agroecologist and program director and farm manager at MFAI, teamed up with Soledad Orcasberro, a Ph.D. student in the Department of Plant and Agroecosystem Sciences at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and her advisor, Valentin Picasso. In addition to surveying farmers about their establishment methods and field management, the researchers gathered alfalfa yield and soil health data from participating farms to find similarities among those with the most productive forage stands.

The observational study was an extension of a Midwest Forage Association project and was funded by the Alfalfa Checkoff program through the National Alfalfa and Forage Alliance (NAFA). It included data from 66 alfalfa stands among 24 producers across Wisconsin, Michigan, and Illinois. Orcasberro conducted interviews and took soil samples at the various locations between the 2021 and 2022 growing seasons, and producers submitted forage samples and yield data after each alfalfa cutting.

After analyzing the preliminary results, the researchers identified key practices and soil properties that seemed to correlate with the best alfalfa yields across the board.

More cuttings equal more yield

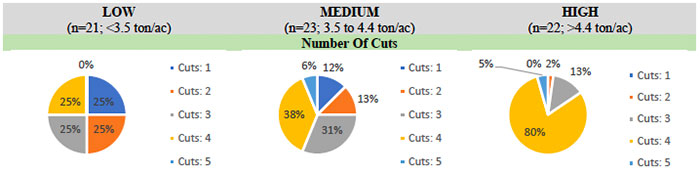

The number of cuttings was the most prominent divider of low-yielding and high-yielding alfalfa fields in the study, with the most productive stands being cut more frequently. In fact, 80% of the fields with the best yields were cut four times a year, and 85% were cut four times or more. Only 25% of the alfalfa fields with the lowest yields were cut four times a year.

Orcasberro explained that farmers who stick to shorter harvest intervals stimulate more regrowth over the course of a growing season, and thus, achieve better yields. Despite the perceived yield gain that could occur with longer rest periods, she said plant growth rates eventually taper off as alfalfa becomes overmature.

“The ones who had the higher yields are the ones who cut at least four times,” Orcasberro reiterated. “If you wait too long, you are being less effective because you are losing yield and quality, and you are not taking advantage of the crop.”

Another practice that correlated with better forage yields was applying potassium (K) and sulfur (S) or spreading manure during alfalfa establishment. Tautges pointed out that using fertilizer inputs might not reap instant rewards because alfalfa yields tend to be lower in the seeding year, regardless of fertilization. Nonetheless, K and S at establishment appeared to benefit forage production in second- and third-year stands.

“Investing in the nutrients of your field in that first year of establishment seems key for increasing yields throughout the life of the stand,” Tautges said. “I can see why farmers wouldn’t necessarily do this because you don’t expect very high yields during the establishment year. But for those who do, it is enhancing their yields later on. It seems worth it.”

Tillage also seemed to influence alfalfa yields, and the researchers found the strongest relationship between vertical tillage and the least productive stands. Nearly 75% of the low-yielding fields were vertically tilled, whereas vertical tillage was only implemented on 56% and 47% of the medium- and high-yielding fields, respectively. Tautges suggested that since vertical tillage causes pan compaction, it can interfere with root growth, compromising seedling establishment and stand persistence.

A greater proportion of the medium- and high-yielding fields were conventionally tilled, likely creating a more suitable seedbed. Additionally, 6% and 13% of medium- and high-yielding alfalfa was no-tilled, but none of the low-yielding alfalfa was. The researchers concluded both conventional tillage and no-till have potential to bolster forage production, but they would advise against using vertical tillage.

Soil carbon is critical

The other aspect of the three-legged study was soil health and fertility. Management can impact the physical, chemical, and biological properties of soil, and these properties consequently affect alfalfa productivity. The researchers collected soil samples from 44 of the 66 farms that participated in the study and found the highest yielding alfalfa grew in soils with the greatest soil organic matter, and thus, the greatest concentrations of active carbon, which promotes microbial activity.

“The book value assumption is that soil organic matter is 57% carbon on average, so you can take your soil organic matter level and multiply it by 0.57 and you will be estimating your soil carbon,” Tautges explained. “Active carbon is just one subset of soil carbon — it is the biologically available carbon that microbes eat.”

Higher levels of soil organic matter were also associated with a wider range and larger concentrations of other nutrients in the soil, which encouraged more diverse microbial communities.

“We found relationships between the soil organic matter and the macronutrients and the microbial community,” Orcasberro said. “The research shows there is an association between the carbon pools and the microbial activity of the soil and the yield. That is very interesting, and we are still [analyzing] it.”

While the researchers focused on the aspects of field management and soil health that appeared most relevant to alfalfa production, they also noted factors that were not observed to effect forage yield. For instance, farmers who grew Roundup Ready alfalfa did not realize better yields than farmers with conventional varieties. Further, there was no significant difference in yields between organic and conventional operations. The researchers acknowledged these practices may boost yields in some cases, but they were not associated with better alfalfa production on the farms that participated in the study.

Tautges and Orcasberro will continue analyzing these preliminary results, and they plan to evaluate how field management and soil health impact forage quality in addition to forage yield. With that said, they hope their on-farm research resonates with alfalfa producers and gives them a fresh perspective of the principles of alfalfa production that are demonstrated in university and commercial trials.