As people gathered in Punxsutawney, Pa., to see whether the infamous groundhog with the same namesake would see his shadow, hundreds of others attended the CattleFax Outlook Seminar on the main stage of the Cattle Industry Convention in Orlando, Fla., to hear a more thorough weather forecast for 2024.

While the promise of an early spring from the renowned rodent may lift the spirits of those experiencing a weary winter, weather outlooks based on historic data and meteorological models are more valuable for forage producers as temperature and precipitation predictions paint the picture for crop yield and quality in pastures and hayfields.

The basis for such weather outlooks is the oscillating surface temperature of the central and eastern parts of the Pacific Ocean, also known as El Niño and La Niña. El Niño takes effect when surface temperatures are warmer than normal, and below average surface temperatures favor La Niña. While these weather patterns are likely well-known among agriculturalists, the transition period from one phenomenon to the other can create some uncertainty.

During the seminar, Matt Makens shared the impacts of the current transition from El Niño to La Niña. Makens, a meteorologist and atmospheric scientist with Makens Weather LLC based in Colorado, said La Niña could come back with a vengeance as El Niño departs after its peak influence that occurred in December.

“We are at a peak now, and El Niño is as strong today as it’s going to be,” Makens stated. “History says we have La Niña in place by this summer; the models say we have La Niña in place this summer.”

Before discussing what La Niña has in store, Makens summarized the impacts El Niño had in 2023, which was the fourth-strongest event of its kind in over four decades. After getting a slow start last summer, some much needed moisture alleviated drought conditions in the West, parts of Texas, and southern and central Florida. Makens considered this a positive outcome of El Niño, and one that will continue for the next few months as the weather pattern phases out.

Looking at historical data of El Niño years since 1980, most subsequent growing seasons have been impacted by weather that is warmer and drier than average. Makens pointed out sea surface temperatures in the critical area of the Pacific Ocean have already begun to cool, and the rest of the observed zone is expected to follow suit in the coming months. This will ultimately push the jet stream higher over the United States and Canada, welcoming La Niña’s warm and dry conditions by the end of the year.

In addition to analyzing sea surface temperatures, Makens compares other factors of previous La Niña years — such as drought severity and snowfall average — to make the most accurate predictions for the coming season.

“All the factors come together like gears in an engine,” he said. “The statistical strengths of previous years show where this year is headed.”

Change on the horizon

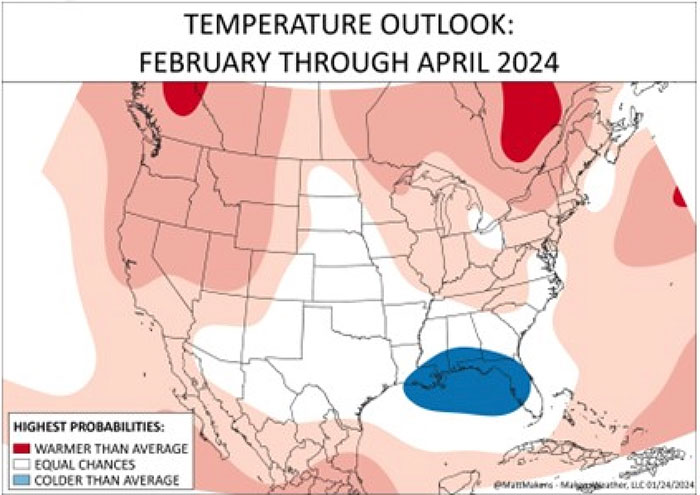

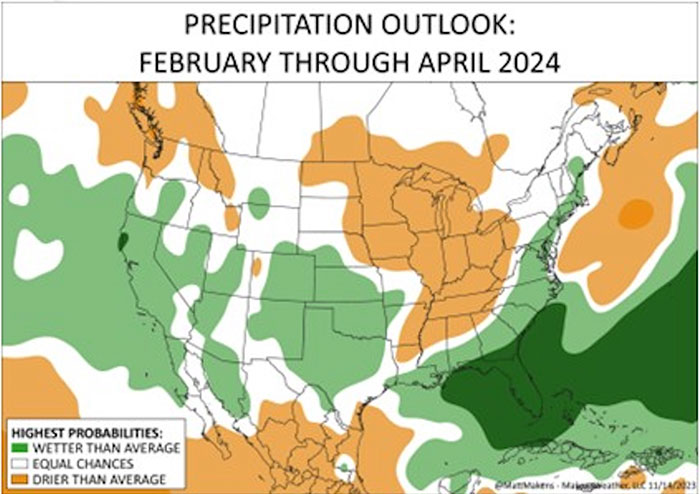

Taking all of the data into consideration, Makens expects most of the central and southern states to remain wetter than normal as El Niño fades away. And while the northern tier of the United States will see above average temperatures this spring, cooler weather will linger in the Central Plains and the South, which may have implications on calving season.

“If you’re calving, now or soon, your risk of cold impact on those calves is highest over the next six weeks or so,” Makens cautioned.

He added that greater precipitation across the Central Plains and the South should provide an early growing season for forages and winter annuals, assuming hayfields and pastures don’t get too much moisture. This will allow a stronger start to the year than what was seen in 2023.

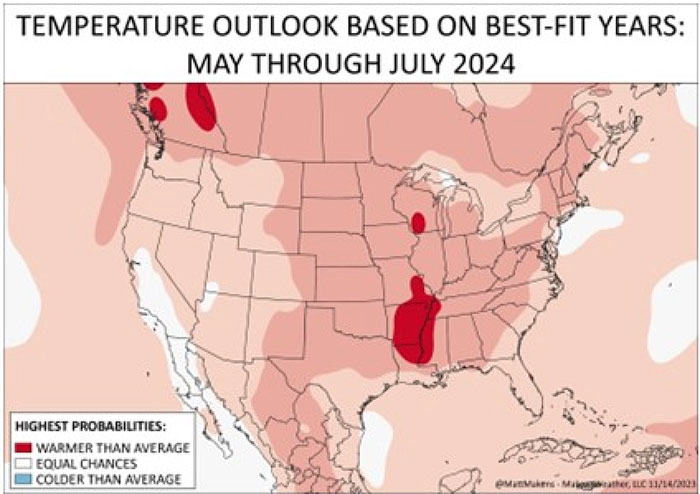

Looking at later months, Makens said conditions will either settle in neutral territory or make a full transition to La Niña. The former scenario would be beneficial for farmers and the agricultural industry as a whole; however, most models predict the latter scenario will prevail.

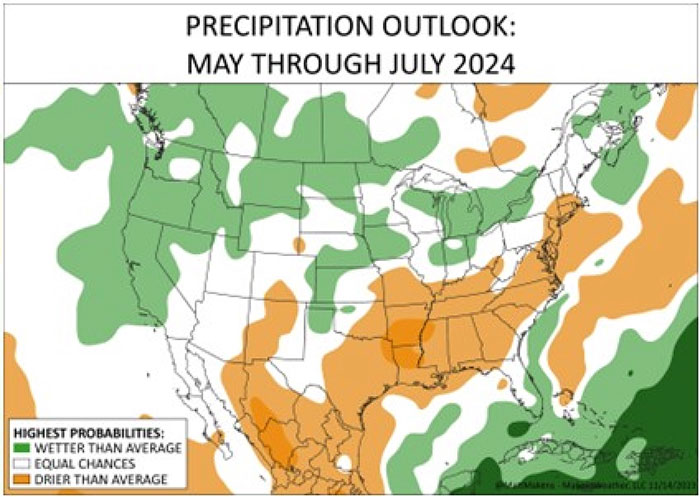

“With La Niña in place by summer, the impact won’t be huge just yet, but the trend will progress as we go forward in time,” Makens explained. “Dryness will increase in the Central and Southern Plains, and we will start to get that moisture back in the North.”

In other words, temperature and moisture trends could flip-flop on a map of the U.S. between May and July. At that point, the Northern Plains and part of the Midwest might experience greater precipitation while the rest of the country could start seeing longer stretches between rainfall events. Despite the negative effects this could have on the second half of the growing season, Makens suggested the additional moisture this spring could hold off drought in parts of the South to some extent.

In closing, Makens shared his greatest concern is the duration of the looming La Niña. Unlike the latest El Niño, he anticipates the warm and dry weather to be a common theme for multiple years, not just one. With that said, the recent relief felt across the South and the West may not have been enough to deter future drought, which could start to set in again as early as March.

“History suggests it will be robust,” Makens said of the coming year. “We’ve had favorable moisture that will help with spring growth and will carry over into summer for a lot of us. Then the drought will come back.”