The author is an associate research and extension professor with Mississippi State University at the Coastal Plain Branch Experiment Station in Newton, Miss.

Net farm income is predicted to have declined nearly 20.9% since 2022, with substantial losses in crop receipts and continued pressure from rising costs and inflation. During such times of economic downturn, integrating livestock onto traditionally farmed ground may offer a source of revenue that in most other years might not make sense . . . or cents.

Interest in grazing cover crops has climbed over the last decade with greater pressure and awareness of the resiliency of our agroecosystems, and integrated crop-livestock systems have shown the capacity to enhance subsequent crop productivity, diversify agroecosystem form and function, advance soil ecosystem services, and generate more revenue. Combining highly nutritious cover crops as a source of forage for grazing ruminants with traditional crop production has the potential to enhance soil structure and biological activity and reduce soil compaction.

Where it fits

In east Mississippi, crop production is limited to remnant prairies with heavier, soils in the north, compared to sandier, soils in the central and southern parts of the state. These sandier soils are typically lower in overall fertility, more prone to drought, and are predominantly used for timber production. However, there remains a significant amount of acreage dedicated to stocker cattle production and the utilization of cool-season pastures in that part of the state.

In the past, I have proposed integrating livestock onto cropland to farmers, which is where the eye rolls tend to begin. More recently, I’ve shifted my focus to encouraging stocker cattle producers, who typically don’t utilize pastures during the warmer months when gains suffer to consider adding a soybean crop after grazing these cool-season annuals to make better use of their land base and to boost revenues. Also, with reduced market prices for soybeans and corn along with higher inflation and input costs, now may be the time to consider combining cattle and crops to spread out financial risk.

Tried and tested

To evaluate this, researchers conducted field trials across three locations in eastern and central Mississippi over the past several years. These trials included grazing combinations of oats, crimson clover, and radish, followed by soybean; grazing cereal rye, crimson clover, and radish followed by continuous corn; and grazing cereal rye followed by soybean or cotton. The trial location soils have included heavy clay, fine sandy loam, and a silt loam. For this article, we’ll focus on the results from the third mentioned study, where we integrated grazing livestock on cereal rye into traditional soybean production systems.

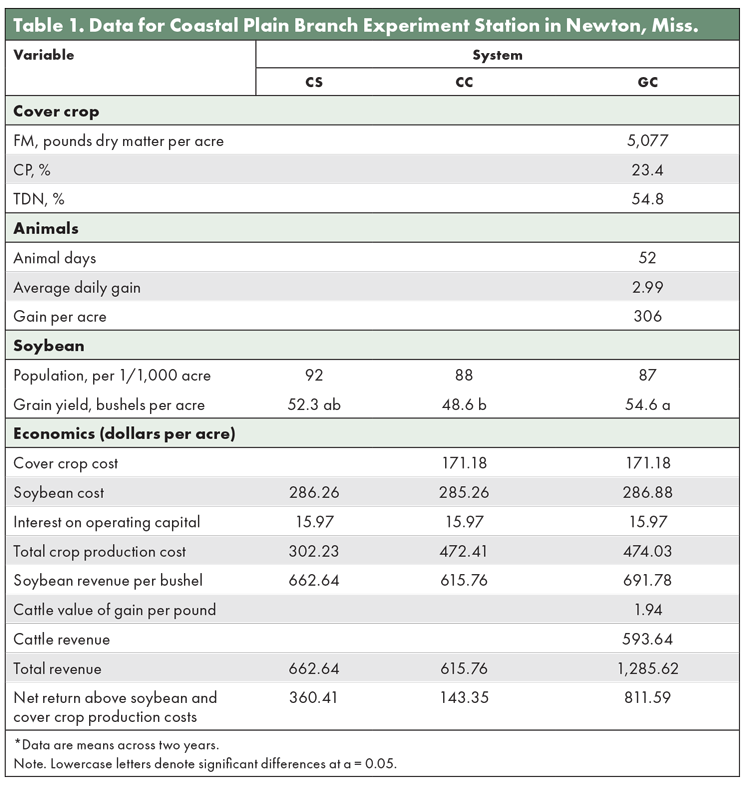

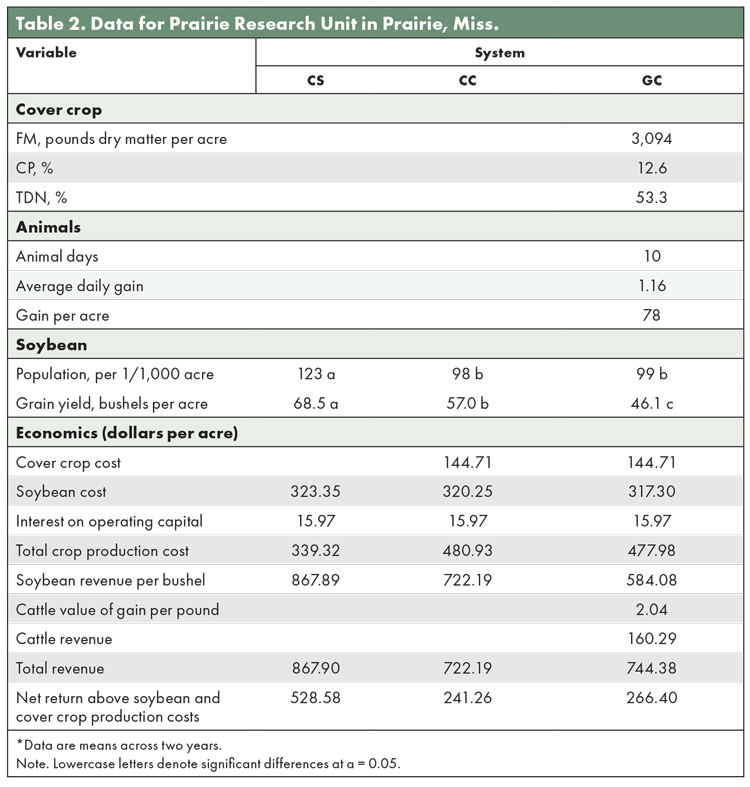

We compared three cropping systems at the Prairie Research Unit in Prairie, Miss., and the Coastal Plain Branch Experiment Station in Newton: conventional soybean (CS); no-till soybean and cereal rye cover crop (CC); and no-till soybean and grazed cereal rye cover crop (GC). At each location, cereal rye was planted in the fall of 2021 through 2023, grazed during the winter and spring for the GC treatment, and terminated in the late spring prior to no-till planting soybeans. Replacement heifers were used at both locations to graze cereal rye cover crops at a target stocking density of 1,500 pounds per acre.

Researchers collected data for animal performance, cover crop production, soybean production, and soil change over time. Also, a complete economic assessment comparing the three systems according to net revenue was generated by location. Let’s concentrate on the forage and grazing and economic assessment.

Grazing results

Cumulative forage mass (FM) was 5,077 and 3,094 pounds of dry matter at Newton and Prairie, respectively. Nutritive values for forage samples collected at Newton were 23.4% and 54.8% for crude protein (CP) and total digestible nutrients (TDN), respectively. At Prairie, mean CP and TDN was 12.6% and 53.3%, respectively.

Animal performance was calculated at each location by assessing animal days, average daily gain, and gain per acre (Tables 1 and 2). At Newton, mean animal days for GC paddocks was 52 days, compared to only 10 days at Prairie. Furthermore, two grazing cycles were accomplished each year at Newton, whereas only one cycle was achieved in 2022 in Prairie when the availability of cover crop biomass was the limiting factor.

Average daily gain was 2.99 pounds per day per head at Newton and 1.16 pounds per day per head at Prairie. Therefore, lower average daily gain at Prairie was a direct result of lower forage biomass and lower nutritive values of cereal rye.

Total gain per acre is the combination of animal days and average daily gain and is directly impacted by forage availability and stocking rate. In the study, total gain was 306 pounds per acre at Newton compared to 78 pounds per acre at Prairie.

Total costs for each treatment by location are found in Tables 1 and 2. Cover crop costs varied by location and planting method. The cost for no-till drilling cover crop seed was $33.04 per acre compared to broadcast seeding, which was $5.05 per acre. Soybean cost varied by treatment within each location because of grain hauling costs that were incurred based on mean grain yield for each treatment.

Total production costs per acre at Newton were $302.23 for conventional soybeans, $472.41 for cover crop systems, and $474.03 for the grazed cover crop treatments. At Prairie, production costs for the same treatments were $339.32, $480.93, and $477.98 per acre.

Soybean revenue was calculated using the Mississippi Soybean Planning Budget statewide average price of $12.67 per bushel. Mean soybean revenue per acre was $662.64, $615.76, and $691.78 at Newton, and $867.89, $722.19, and $584.08 at Prairie for the CS, CC, and GC treatments, respectively.

Researchers determined cattle revenue was $593.84 and $160.29 per acre for Newton and Prairie, respectively. This value was then divided by gain per acre, resulting in a value of gain of $1.94 and $2.04 per pound for Newton and Prairie, respectively.

Total revenue was determined by adding soybean revenue with cattle revenue. Total revenue per acre at Newton was $662.64, $615.76, and $1,285.62 for the CS, CC, and GC treatments, respectively. At Prairie, total revenue per acre was $867.89, $722.19, and $744.38 for the same respective treatments. Net returns above soybean and cover crop costs — revenue minus costs — were $360.41, $143.35, and $811.59 per acre for CS, CC, and GC treatments at Newton. At Prairie, these same treatment net returns were $528.58, $241.26, and $266.40 per acre.

Soil dictates success

Results from these field trials comparing conventional soybean production with and without a grazed cereal rye cover crop on two distinctly different soil types indicate that the combination of no-till soybeans and a grazed cereal rye cover crop more than doubled net returns per acre on a fine sandy loam soil. However, as observed at Prairie, the same combination of no-till soybeans and grazed cover crops resulted in substantially lower revenue than conventional soybean production on heavy, poorly drained clay soils.

On coarse-textured, well-drained soils, there are opportunities for greater revenue through the implementation of integrated crop-livestock systems. Our research contributes to the growing precedent of research that demonstrates the economic impact that the diversification of agricultural enterprises, particularly in cattle and row-crop systems, can have in the Coastal Plain region of the Southeast. The utilization of cover crops by cattle has been shown to more than offset the costs of adopting cover crops and can generate additional revenue for the landowner.

This article appeared in the January 2025 issue of Hay & Forage Grower on pages 24-26.

Not a subscriber?Click to get the print magazine.