Why are we always talking about La Niña? Doesn’t she get tired of thwarting crop growth with dry weather and threatening farmers with drought conditions?

According to Matt Makens, the country appears to be in the clutches of La Niña once again. The meteorologist and atmospheric scientist with Makens Weather LLC based in Colorado shared his insight on the long-term weather forecast during the CattleFax Outlook Seminar last week at the Cattle Industry Convention in San Antonio, Texas.

To begin, Makens reminded the audience that at this point last year, El Niño was in full effect. In fact, the lowest drought impact in the last four years was reported during the first six months of 2024. That was pretty remarkable for such a short-lived and relatively weak El Niño event, Makens said. But that all changed in June.

“June was one of the most rapid redevelopments of drought that we have ever recorded,” Makens said. Although this transition began last summer, it wasn’t until December that La Niña officially arrived.

The sea surface temperatures of the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) region influence weather patterns that occur for months, or even years, to come. In general, warmer sea surface temperatures in this critical area of the Pacific Ocean indicate El Niño, creating milder temperatures and wetter conditions across the United States. Cooler sea surface temperatures tend to push the jet stream higher over the country, welcoming warmer, drier La Niña conditions.

But sea surface temperatures and atmospheric conditions don’t always work in tandem. The effects of the changing ENSO can be delayed as the atmosphere “wiggles around,” Makens said. For example, he noted that even with a looming La Niña last fall, many farmers throughout the Central Plains experienced well-timed rainfall in late October and early November. By late spring and early summer, though, there is a greater probability that La Niña will show her true colors.

Think about what happened on your farm during the years of 1993, 2004, 2017, and 2021. Makens said these are potential analog years according to his probability-based system that he used to paint the picture for 2025. He combined historic data and meteorological models to predict long-term forecasts that are more accurate than average temperature and precipitation trends.

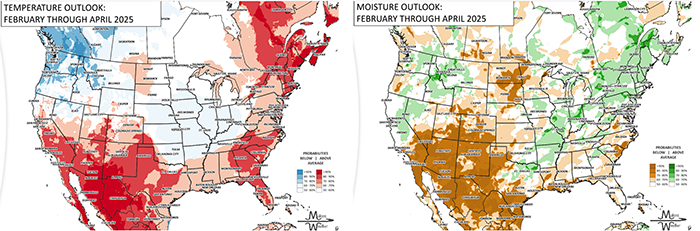

February through April

For the rest of February through April, Makens said the temperature outlook is warmer than average; however, he made note of hints of cooler weather throughout the Midwest, especially over the next several weeks.

In terms of precipitation, the moisture outlook for the same time period shows the most dryness throughout the Southwest and portions of the High Plains. Even though the latter region has received significant snowfall so far this year, Makens purported this won’t translate to enough moisture to counteract La Niña’s drought effects.

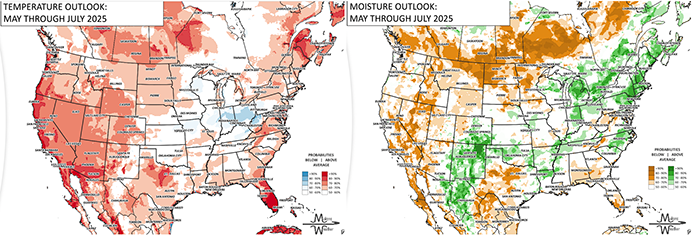

May through July

High heat in the Southwest and along the West Coast is likely as we enter the summer months, whereas Makens expects to find cool pockets throughout the Corn Belt. Even farther east, a splash of blue across parts of Indiana, Ohio, and West Virginia indicates an 80% to 90% probability for below-average temperatures during May through July.

Makens said historic data supports a stronger monsoon season compared to last year; however meteorological modeling does not back that up. Even so, he expects weather models to change over the next few months, favoring more precipitation in parts of the Southwest than what they currently suggest.

Although the Corn Belt and most of the East Coast also have a greater probability of receiving above-average moisture during May through July, Makens gave a stark disclaimer.

“Whether it be Iowa, northern Illinois, or southern Wisconsin, somebody in that region is going to be downright dry from mid-June through mid-July,” he said. “There is likely going to be a pocket there where we will use the term ‘flash drought.’”

A more predictable dry pattern is expected in many of the states that share a border with Canada, including parts of Montana, North Dakota, and Minnesota.

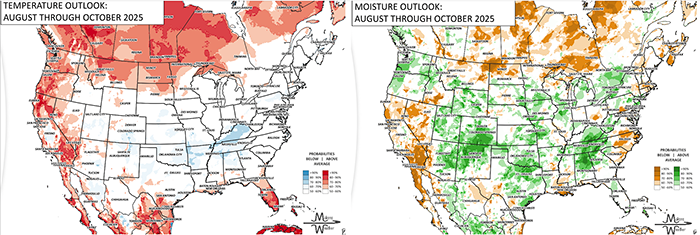

August through October

Looking further into forecast, it becomes more difficult to determine the probabilities of warm versus cool and wet versus dry. Moreover, Makens stated the long-term temperature and moisture outlooks largely depend — and will likely change — according to the strength of the early summer monsoon coming from Mexico.

After balancing the biases of meteorological models, he pegged most of the central and eastern United States to be relatively cool in August through October, with drought growing across the Northern Plains and Pacific Northwest.

The probability for above-average moisture appears to be high starting in the Southwest and spreading throughout the center of the country. In fact, Makens expected to see a situation similar to last fall take shape, providing adequate precipitation to many hay and row crop regions in mid- to late fall.

It might be neutral

What if La Niña’s bark is worse than her bite? Makens said it’s important to consider what happens if we get stuck somewhere on the spectrum of El Niño to La Niña. In this case, drought is still expected throughout heavy cattle-feeding areas of the Central Plains, although not to the degree of what would be expected during a full-blown La Niña.

“We will continue to refine the probabilities of that event going forward,” Makens affirmed.