Farmers can add weed control to the long list of benefits gained from growing alfalfa in crop rotations. According to Mark Renz, being a dense stand of perennial forage that is cut several times a year is a form of weed control in itself, and one that can tackle even the most problematic of pests.

Earlier this month, Renz took the Dairy Forage Seminar Stage at World Dairy Expo in Madison, Wis., to explain how adding alfalfa to annual crop rotations can improve weed management. Before narrowing in on its contributions to weed control, though, the extension weed specialist with the University of Wisconsin-Madison advocated for alfalfa as a cornerstone component of dairy operations overall.

Alfalfa curbs soil and water runoff, reduces nutrient leaching, and improves soil health. Its ability to fix nitrogen in the soil reduces the need for nitrogen fertilizer, and subsequent crops can experience better yields thanks to the rotation effect. Raising the inclusion rate of alfalfa in dairy rations can also boost milk production and animal health.

In addition to these attributes, Renz said alfalfa can be extremely aggressive. The mechanisms that make it a powerful tool for weed control include early spring green up and canopy closure, high stem density, and multiple harvests, which prevent weeds from going to seed. This is what gives alfalfa a competitive edge against two problematic herbicide-resistant species: tall waterhemp and giant ragweed.

But in order to realize sufficient weed control, alfalfa must be well established and not stressed. Renz said one of the biggest barriers to successful alfalfa establishment is herbicide carryover. This is especially common when farmers apply residual herbicides to kill stubborn weeds in corn and soybeans during the previous year. The issue worsens as those products are applied later in the season and under drought conditions.

“We tend to see carryover in drought years because herbicides break down with moisture,” Renz explained. He encouraged the audience to follow label instructions and obey alfalfa plant-back restrictions. Other stressors that can impede alfalfa’s competition with weeds include disease pressure, winterkill, insect injury, and poor soil fertility.

A worthy opponent

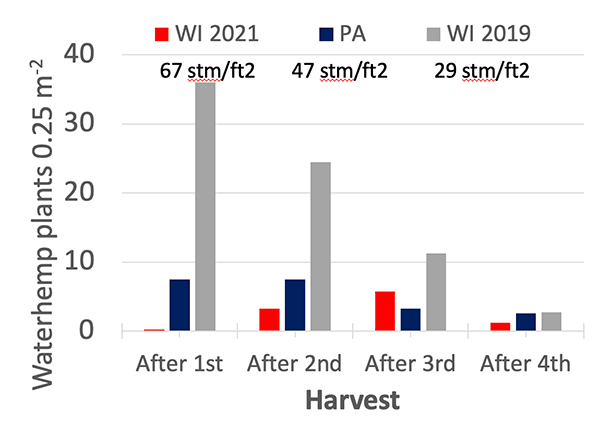

To demonstrate how stand establishment affects alfalfa’s ability to control weeds, Renz showed results from a study across three locations — two sites in Wisconsin and one in Pennsylvania — that compared alfalfa and waterhemp densities. Researchers found waterhemp emergence remained low when alfalfa stem density was at or above 40 stems per square foot.

At one of the Wisconsin locations, alfalfa stem density was below that threshold — roughly 29 stems per square foot — but waterhemp density still declined with each forage harvest. “Even though we didn’t have competitive alfalfa, the mowing of those plants still left us with low waterhemp density,” Renz said.

Renz added that when weeds were present, they didn’t affect forage quality. Additionally, only some waterhemp plants produced seed, and those that did only produced about 50 seeds per plant. “That is very different from waterhemp in corn or soybeans that is producing tens of thousands of seeds per plant,” Renz asserted.

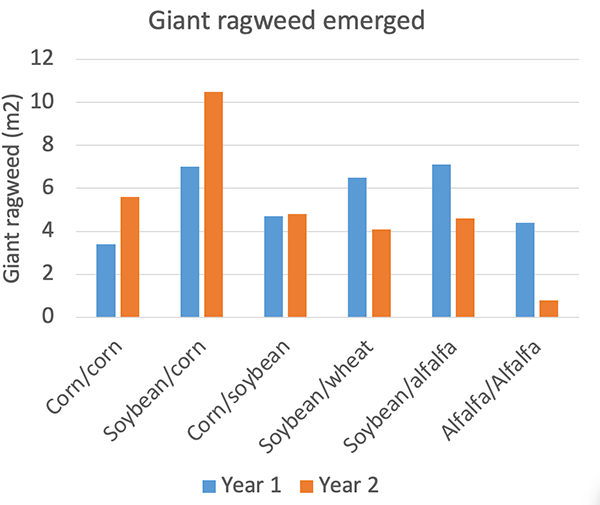

He presented another study from Minnesota showing similar results with giant ragweed. Researchers from the Gopher State evaluated several two-year crop rotations, including corn-corn, corn-soybean, soybean-wheat, soybean-alfalfa, and alfalfa-alfalfa. By the second year of the experiment, giant ragweed populations were lowest in the alfalfa-alfalfa rotation.

“The researchers concluded that the inclusion of alfalfa in a cropping system has the greatest potential to improve giant ragweed control,” Renz said.

Less herbicide, less money

To evaluate alfalfa weed control from an economic perspective, Renz referred to results from the Wisconsin Integrated Cropping Systems Trial in Arlington, Wis., from 1989 to 2024. The trial included three treatments: continuous corn, a corn-soybean rotation, and a four-year rotation of one year of corn followed by three years of alfalfa. All three systems were aggressively managed for weeds.

Researchers have evaluated several factors in these fields throughout the study, but Renz analyzed the data for late-season weed biomass and weed seed density in the soil seedbank to estimate the effectiveness of weed control methods long term. Although late-season weed biomass and seedbank density declined across all treatments over time, weed management costs were significantly lower when alfalfa was in the picture. These were estimated to be $35 to $45 per acre compared to $70 to $80 per acre for continuous corn and the corn-soybean rotation.

“Part of this is herbicide cost, and the other issue is that we are applying more herbicide,” Renz said about higher inputs for continuous corn and the corn-soybean rotation.

For those trials, researchers routinely applied herbicide two to three times per year. For alfalfa, they sprayed stands one to two times during the establishment year but then applied herbicide the following years only as needed. He added that researchers have changed their approach to weed management in the continuous corn and corn-soybean rotation to improve control over time, but weed management in alfalfa has remained the same.

“Where farmers are planting alfalfa in Wisconsin, we are getting a lot of benefits throughout that rotation. We have agronomic benefits, we have environmental benefits, we have economic benefits, and we get plenty of benefits from weed management,” Renz concluded.