The author is a forage consultant in Bay City, Wis.

Several years into my forage career I encountered a high-producing, well-managed herd struggling with managing forage piles. It wasn’t that they couldn’t manage all the plastic and tires that came with piles. They just really, really disliked nearly every aspect of successful pile management. This herd was on track for a rapid rate of expansion, and they preferred to put their limited resources to other areas. Yet, quality forage was needed to feed the cows and maintain the excellent production this herd was justifiably proud of.

Their nutritionist and I looked at every angle of those piles. We discussed proper packing and proper covering, the correct number of tires, correct sizing, and pile placement. We calculated the dollar value of the massive amounts of shrink they were experiencing. Still, it was clearly not working. They refused to consider proper pile management. They understood the problem, yet the solutions we offered simply did not resonate with them or their systems. In the end, the farm, not the so-called experts, solved their forage dilemma.

They bought one of the first 14-foot baggers in the Midwest and proceeded to harvest excellent-quality alfalfa and corn silage, as they had done prior to the expansion. They laid those perfectly packed bags on the solid asphalt pad that was previously the site of the previous ill-fated piles. In the process, they taught us there was more than one way to store forages on large farms.

Bags offer flexibility

Silo bags carry advantages that are sometimes overlooked. Initially, they can offer a lower capital investment during times when cash flow may be limited, as often is the case during a farm expansion. Bags are flexible, can offer temporary storage solutions, and can be adapted for large and small herds. Feed is easily inventoried and can be as simple as using a can of spray paint to mark the field, forage quality or crop on the side of the bag. Safety hazards such as silage avalanches, falling tires or chunks of ice are also reduced for personnel working around bags.

Potential drawbacks include the large footprint needed to store forage and the large quantities of plastic needing disposal. Similar to piles and bunkers, the forage is stored under plastic and prone to rips and tears. This requires regular inspection to repair damage and maintain quality. Due to the smaller surface area on the feeding face, moisture variation can happen rapidly; this may cause ration dry matter adjustments to be missed.

Properly managed bags have the potential to store some of the lowest shrink and best fermented forage compared to other storage systems. The balance of this article will discuss key management factors essential to maintain forage quality in bags.

Siting is important

With bunkers and piles, the person on the pack tractor is a key ingredient to the production of quality forage. For bags, this role shifts to the person running the bagging equipment. A good working knowledge of the bagging equipment and how to properly set up and run the equipment is instrumental to maintaining forage quality in storage. The person monitoring the bagger needs to ensure the forage is loading evenly to the packing knives and that brake tension is properly set and routinely checked. Other equipment settings and maintenance factors need to be a part of the operator’s checklist.

Other key areas include site selection, proper crop moisture, crop maturity, correct bag size relative to the herd size, and desired feedout rate.

Site selection requires careful consideration of topography, the feeding systems employed and environmental conditions during the entire year. Improper site selection can quickly turn a lower initial capital storage system into an expensive nightmare. Because of the flexible nature of the bags and bagging equipment, poor site selection is common. How many of us have seen bags surrounded by a sea of mud?

Ideal site selection for bags includes a solid, smooth, well-drained surface with an eye toward water flow. Asphalt or concrete are ideal. If finances are tight, the site can be prepared as it would for asphalt and then utilize packed limestone or road re-grind over crushed rock as the base. The key is to pack and level the surface similar to building the base for laying concrete or asphalt. A well-prepared surface often pays for itself within a year or two due to reduced feed shrink, less dirt contamination, better quality fermentation and pack, and reduced animal health concerns.

A good question to ask when considering the site is: Will this site (ground) support the heavy equipment needed to fill and empty the bags at any time during the year?

For those in Northern climates, consider orientating bags north to south and feeding out of the south end during winter to help alleviate frozen silage chunks. Locate the site away from woods, corn and soybean fields, and old buildings to lessen damage from wildlife. Mowing weeds and grass regularly and disposing of trash and unusable feed will minimize areas where critters can hide, giving ready access to your bags.

Additionally, be wary of the potential damage to bags from livestock, pets and even children. Small holes, scratches and puncture marks can lead to a massive amount of spoilage due to oxygen infiltration. Left unrepaired, one small puncture can lead to many tons of spoiled feed.

No duct tape

Storing tape in a container near the bags, on a nail in a nearby shed, or in the TMR tractor or truck can help ensure holes get repaired immediately versus forgotten in the mix of everyday life. Be sure to use tape designed for agricultural plastic. High-quality bag tape has built-in UV protection, adheres to the bag, and will not degrade. Duct tape is not acceptable for bag repair.

While repairing punctures is inevitable, prevention is better. Methods to help protect bags have ranged from such inexpensive measures as putting bird netting over bags (make sure netting is elevated off the bags); stringing fishing line from tire to tire sitting on top the bags to prevent birds from landing on the top; electric fencing set up around the bags; mothballs; or birdshot; to as expensive measures as bag tarps and solid fences.

Size and seal

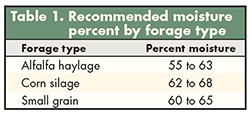

When bagging is done properly, highly efficient and quality fermentations will occur. Proper moisture for different crops is listed in Table 1.

Bags that are immediately sealed at the correct moisture will potentially produce gas quickly, which is a normal fermentation. This gas needs to be monitored so it does not damage the bag. If needed, cut a slit or use a commercially available vent to release this gas. Remember to reseal or close this opening since failure to do so can result in spoilage.

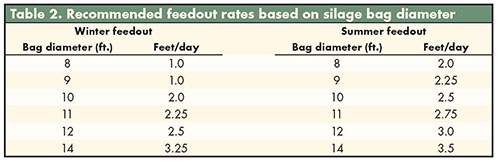

Another common area of bag mismanagement is correct bag sizing. Similar to other storage structures, bags need to be sized for proper feedout. Improper sizing can quickly lead to spoilage and large losses of dry matter, feed quality and lost animal production. Recommended feedout rates for summer and winter are presented in Table 2.

Think of the silage bag as an upright silo laid out on its side. Unlike the upright silo, forage is not getting compacted from the weight of silage above it. Less forge compaction leads to more air ingression into the silage face once opened. Haylage bags, in particular, are prone to oversizing and more difficult to smoothly pack. When in doubt, select a smaller bag for optimal forage quality.

In summary, bags can be an excellent method to store high-quality forage on many farms and should be carefully considered when looking at new forage systems.

This article appeared in the March 2016 issue of Hay & Forage Grower on pages 6 and 7.

Not a subscriber? Click to get the print magazine.