Information in this article is based on a presentation delivered by Monte Rouquette Jr. at a recent grass-fed beef production conference held on the Texas A&M University (TAMU) campus. Rouquette is a TAMU Regents Fellow and professor at Texas A&M AgriLife Research.

Rouquette noted that both the growth and utilization of forages for grass-fed beef are closely linked. Degree of utilization has a large influence on the amount of forage produced by plants, and growth is responsible for the amount of available utilization.

Forage production is also dependent on soil fertility, rainfall, and temperature. Fertility is manageable on improved pastures, but the operator can do nothing about rainfall and temperature. Stocking flexibility is important for easing the effects of weather variability on forage production. Cattle stocking rates have a direct influence on forage utilization, animal performance, and acceptable carcass quality; so, they are a very important component of pasture management.

When planning for year-round forage production, there are several factors to consider. Adapted forage species differ across various climatic-vegetational zones of production. Even within the same zone, seasonality of forage production varies and forage nutritive values change with weather and other environmental characteristics.

A target average daily gain (ADG) of 2 pounds per day is needed to put enough fat on an animal to produce a desirable carcass. This means that the animals will need to maintain a body condition score of 6 or better. Desired total body weight at harvest and ADG determine how long the calf will need to be fed.

A plan is needed

A certain amount of forage quantity and quality are required to produce the desired ADG. Forage quantity is measured as dry matter, and forage quality is primarily determined by crude protein and total digestible nutrients (TDN).

Grass-fed beef producers can learn forage management techniques from stocker operators who normally feed minimum amounts of supplements. There are forage systems in the southern United States that produce 2 pounds per day ADG on stockers year-round.

Cool-season annuals in the systems are small grains grazed from December through April, annual ryegrass utilized from January through May, and clovers that are available for use February through May. Warm-season annual grass provides good grazing in May through July. Dry matter requirements are met with these annual grasses during July through October, but supplement is needed to fulfill nutrient requirements during the late summer and fall.

Supplement requirements do not make these systems unusable for grass-fed producers. Forage based supplementation is acceptable as long as it doesn’t contain grain. Good-quality hay, silage, or haylage meet supplement criteria for grass-fed beef. Cornstalks are considered forage if they don’t contain grain.

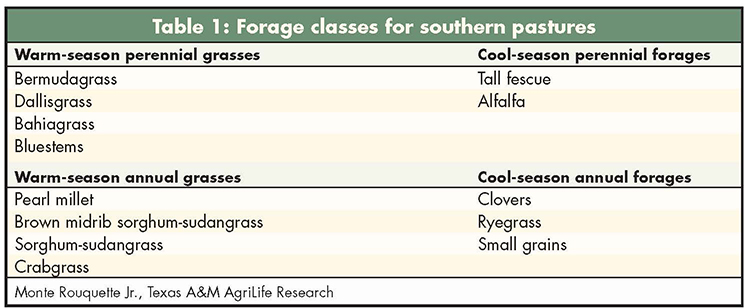

Warm-season perennial grass provides good grazing from April through June and again from July through October with supplementation during the latter period. Forage classes for southern pastures and some of the species within each class are shown in Table 1.

Grass-fed beef producers should develop forage calendars that are applicable to their area and use them to design a year-round forage system. Silage or some form of harvested forage may have to be fed during winter when snow covers the ground. The forage calendar example presented in Table 2 demonstrates the ability to provide year-round grazing and production overlaps of the various classes of forage.

Southeast forage types

Warm-season perennial grasses are the foundation of pastures in the southeast United States. These grasses produce the highest amount of dry matter per acre and provide the most sustainable pasture systems. The bad news is that they are in the lowest nutrient category of all forages. Common warm-season grasses used in the South are Tifton 85 bermudagrass, Coastal bermudagrass, bahiagrass, and native grasses. Nutritional value of bermudagrass and other warm-season perennial grasses is limited by their relatively high concentrations of fiber and lignin that reduce digestibility.

Tifton 85 has higher dry matter production and drought tolerance than other bermudagrasses. It has lower lignin concentration than Coastal bermudagrass and higher digestibility. Because of these characteristics, it provides superior animal performance over the other bermudagrasses.

Warm-season annual grasses are ranked medium in nutritive value and include brown midrib sorghum-sudangrass, pearl millet, and crabgrass. Sorghum-sudangrass is a hybrid of forage sorghum and sudangrass. The brown midrib mutation has less lignin than conventional varieties, which makes them more digestible by cattle.

When crabgrass is mentioned, most of us automatically think of it as a lawn weed. However, it is a high-quality, very palatable grass that provides excellent grazing during the summer.

Cool-season annuals have high nutritive value when grazed before seedhead development. This class includes small grains (wheat, oats, and rye), annual ryegrass, clovers, and other legumes.

When establishing year-round pasture systems, try to incorporate existing forage rather than plowing the whole farm or ranch. Overused native grasses can often be restored through rotational grazing, which allows each pasture a period of rest.

Establishment checklist

Before planting pastures, collect soil samples for analysis. Take 10 to 20 samples per field, and immediately ship a composite sample to a credible soils analysis laboratory. The soil analysis will provide fertilizer recommendations for the designated crop based on soil type and current fertility status. For forage maintenance, take soil samples at one- to two-year intervals, depending on the nutrient status of your soil.

Select forage varieties that provide good production for your climate and soils. To derive maximum value from pasture establishment, use the recommended seeding rate. Before seeding, make sure there is enough soil moisture for seed germination and plant growth. Success of the planting method depends on environment, soil type, weather, and the ranch management system. Normally a prepared seedbed will offer a lower risk for failure compared to sod seeding.

Stocking rates are the most important practice for forage establishment and maintenance. Stock newly established pastures at a lower rate than well-established forage stands.

This article appeared in the August/September 2017 issue of Hay & Forage Grower on pages 18 and 19.

Not a subscriber? Click to get the print magazine