Much like culture varies widely from one region to another, forage quality is known to be strikingly different as well. Though regional management practices such as irrigation, double cropping, or available seed genetics contribute, it’s the growing environment that is usually the driving force behind regional forage quality differences.

Joe Lauer, University of Wisconsin corn specialist, using results from hybrid performance trials, has estimated that the environment contributes as much as seed genetics to how corn silage feeds. Farmers generally assess feed quality based on experience as well as science and learning. Experience helps us to recognize a “normal” feed quality within a region and tends to be the measuring stick against which we compare crop-to-crop or year-to-year performance in terms of yield and quality.

Extreme environmental conditions can result in crops that feed far differently from what we normally experience and may result in forage that feeds similar to “normal” hay, haylage, or silage from other regions. Growers and nutritionists within regions often don’t recognize the substantial differences in their feed relative to those far away. Knowing these differences could be helpful when odd growing seasons occur.

Regions differ

For those who have worked and traveled across the U.S., you’ll recognize growing conditions vary from the East to West Coasts. Southern and Western hay and silage growers tend to experience very warm temperatures (routinely 90°F to 100°F or greater) during growing their seasons. In the Midwest, growers may only experience a handful of 90°F to 100°F or warmer growing days. Recently, I’ve been working closely with growers in the Northeast and learned that farms may not experience intense heat at any point during the growing season.

What impact could growing conditions in these regions have on feeding quality?

Working across the regions, we’ve recognized forages feed differently and hence the resulting diets must be formulated in different ways.

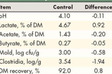

A warm to hot growing environment, provided moisture is adequate, is thought to depress forage quality. Plants may yield better with exceptional growing conditions (sun, heat, and moisture), but stalks tend to grow sturdier, with added lignification. We can visualize regional differences in corn silage feeding quality by comparing corn silage fiber quality between the western and eastern U.S. regions since 2016 (Figure 1). In the Western states, fiber digestibility is typically depressed by the plants growing in a sunny and hot climate relative to the East.

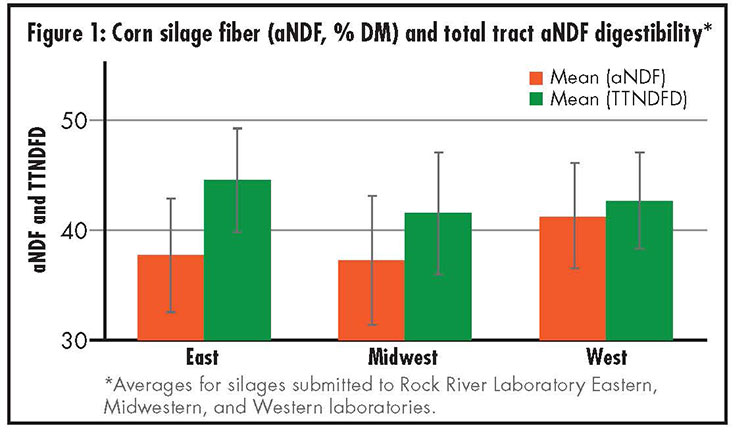

Further, focusing on the Eastern region, we can separate out the Tri-State area (Indiana, Ohio, and areas of Pennsylvania) and compare that to the Northeast (New York, northern Pennsylvania, and Vermont) in Figure 2. Here, the Northeast showcases considerably greater fiber digestibility relative to the more southern, and the likely warmer Tri-State region.

Because of what the cows tell us, I’ve learned that, in general, Northeastern dairies can feed considerably more forage because of better fiber digestibility relative to the rest of the U.S. As such, our definitions of low- or high-forage rations in each region are different. “Low” forage diets in the Northeast are 50 to 55 percent forage whereas “low” forage diets in the Midwest or West are 35 to 40 percent forage.

Factor the environment

What does all this mean to those feeding these forages in their respective regions, and what can we learn?

Pay attention to heat units during the growing season. Fiber is a known bottleneck in dairy nutrition, and it’s influenced by growing conditions. In fact, follow heat units earlier in the season relative to historic trends. Fiber digestibility for corn is likely defined prior to the plant putting on an ear. If heat units accumulate early in the season and later yields are recognized to be strong, consider high-cut silage (12 to 18 inches higher than typical) to improve whole-plant digestibility and leave lignified stalk in the field.

As the harvest wraps up and forage quality is recognized, consider thinking like your neighbors from other regions. Midwestern growers can feed more forage like Northeastern farms if the growing season is cooler than normal, provided inventory allows. As we observed in 2017 in the Northeast, when growing conditions challenge forage quality with extremely hot temperatures or delayed planting, then dairy producers must back forage out of cow diets.

Team up with your consulting agronomist and nutritionist to talk through how the environment may be better factored into your forage plans. There is much yet to learn about the environmental or regional impact on forage quality, but with diminishing dairy and feedlot margins, we need to find new avenues to improve cattle health and performance.

Much like learning new ways to approach life from other cultures can benefit one’s self, learning about forage management or feeding practices from our neighbors in other regions may be one angle to recognize and feed forage for better performance.

This article appeared in the March 2018 issue of Hay & Forage Grower on pages 30 and 31.

Not a subscriber? Click to get the print magazine