Most grazing systems are anchored by perennial forages, which means there are parts of the year when pasture productivity will take a plunge. To fill these gaps and ensure steady feed supplies later into a grazing season, some producers are integrating cover crops into their grazing rotation.

At a field day at the Iowa State Beef Teaching Farm earlier this month, researchers shared results from two projects that examined the benefits of grazing annual forages in the fall and winter. Erika Lundy-Woolfolk, an extension beef specialist, presented information on an initial study that began in Iowa in 2017.

Cow-calf fall grazing

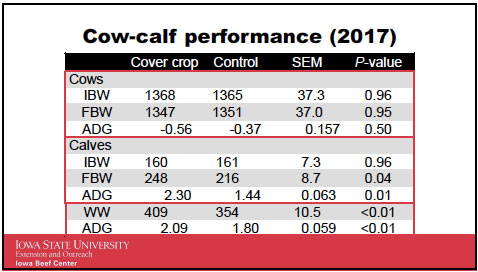

The goal of the study was to compare livestock performance and the economics of cow-calf production between animals grazing cover crops to a control group of those in drylot situations. Every year from late August to early September, species of turnips, radishes, vetch, flax, and oats were drilled into research fields. By mid-November to early December, cows and calves were turned out to graze these acres, and their bodyweights were measured before and after the grazing period.

In 2017, there was no difference in final bodyweight of the cows on pasture and the cows in drylots. However, the calves with access to cover crops were approximately 30 pounds heavier than the calves in the control group, and this weight advantage was maintained until the time of weaning.

“Part of our thought process here was that the females on the cover crop had a higher-quality diet, so they were probably milking a little more and had higher quality milk,” Lundy-Woolfolk explained. “Those calves would have had the opportunity to have a higher quality and quantity of milk, and they were out there with access to the cover crops, too.”

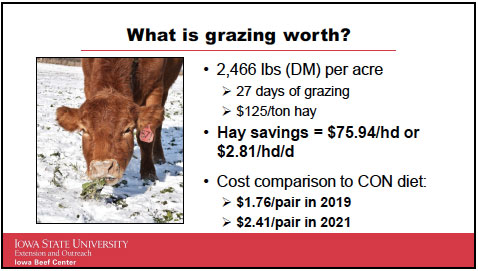

Over the course of five years, this practice has provided an average of 2,500 pounds of dry matter per acre and extended grazing seasons by an average of 27 days. Lundy-Woolfolk estimated this would save roughly $2.81 per head per day in hay costs compared to conventional diets.

Although data has been consistent in most years, dry conditions in 2018 hindered plant growth and there was not enough to graze. Lundy-Woolfolk pointed out that growth is not guaranteed, and an operation can experience a net loss in the case of unfavorable weather. She also warned producers that the oats and brassicas in the study have the potential to accumulate high levels of sulfur and nitrates, which can be harmful to cattle.

Swath grazing

The second study on swath grazing as a winter feeding strategy was presented by Garland Dahlke, associate scientist at the Iowa Beef Center. This practice has been demonstrated on the Iowa State Beef Teaching Farm for the past three years.

In late May or early June, forage sorghum or German millet is no-tilled into the residue of early spring planted oats that had been harvested for hay. Forages are harvested once in July to make hay, and then they are left to grow until just before the first substantial snowfall of the year.

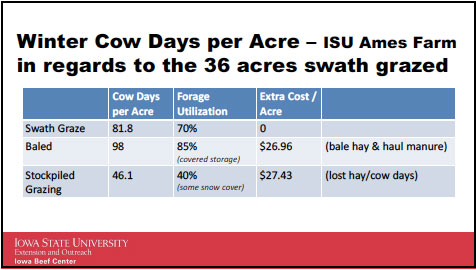

In 2020, forage was cut on December 6 and raked into swaths on December 9. Cattle had access to these acres until late February. Swath grazing allowed about 82 cow days per acre, and the university’s herd of 80 cows utilized 70% of the available forage.

“If we would have baled that hay, we would have probably gotten 98 cow days per acre, and I’d assume about 85% utilization. But that would have cost us about $27 per acre more,” Dahlke stated. “If we stockpiled forage, we would have gotten about 46 cow days per acre, and utilization would have been about 40%. That would have cost us because we would have to feed them more.”

In addition to the economic benefits of swath grazing, Dahlke said the only labor required is advancing an electric fence along the windrows every other day. Animals also tend to stay relatively clean, and field damage is kept to a minimum.

Amber Friedrichsen served as the 2021 Hay & Forage Grower editorial intern. She currently attends Iowa State University where she is majoring in agriculture and life sciences education-communications and agronomy. Friedrichsen grew up on her family’s diversified crop and livestock farm near Clinton, Iowa.