The authors are a plant geneticist and an agricultural information specialist, respectively, at the U.S. Dairy Forage Research Center, Madison, Wis.

It was a grass that time forgot — until a Wisconsin grazier rediscovered it decades later and research showed that it had great potential as a pasture grass. It was almost forgotten again when seed companies gave up on plans to take it to market because it did not grow well in the seed-producing region of western Oregon. But the grass has traits that dairy graziers really desire, so it was given another chance by a farmer willing to accept the challenge of seed production on his own. And if all goes well, Hidden Valley meadow fescue could be on the market by 2017 or 2018.

The story of Hidden Valley meadow fescue begins in 1990 when Charles Opitz of Mineral Point, Wis., noticed an unknown grass growing in a remnant of an ancient oak savanna ecosystem near the location for a new milking parlor. After much research at the U.S. Dairy Forage Research Center (USDA Agricultural Research Service), with assistance from several other labs around the world, we identified this grass as meadow fescue, a close relative of tall fescue and perennial ryegrass.

We believe the meadow fescue came to the unglaciated Driftless Area of Wisconsin, Minnesota and Iowa with early settlers in the 1800s and later was transported with cattle shipped from the southern U.S. Meadow fescue was a popular forage grass, but KY-31 tall fescue replaced it in the Southern states by the 1950s. We have found meadow fescue on over 300 farms in the Driftless Area, so we think that it survived the post-World War II mechanization of agriculture in oak savanna remnants that could not be plowed.

After finding it in 1990, Opitz spread this meadow fescue around his farm by feeding mature hay with ripe seeds to cattle during winter and allowing the cattle to spread the seed in manure pats. It thrived in his pastures. Hidden Valley represents this population of meadow fescue. Plants were collected from the Opitz farm and used to produce seed for testing by the U.S. Dairy Forage Research Center at the University of Wisconsin Arlington Agricultural Research Station.

Excellent forage traits

Since we first produced Hidden Valley seed at the Arlington farm, we have conducted numerous agronomic studies. We have found meadow fescue to be highly winter hardy and drought tolerant. Its adaptation region is the north central and northeastern U.S. and similar regions of Canada.

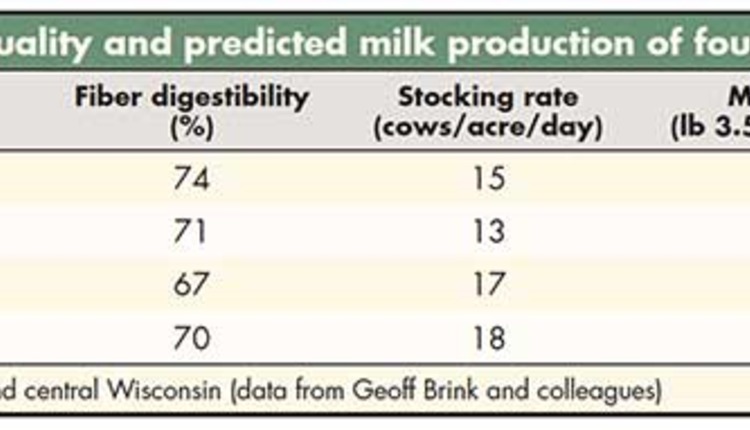

From a dairy nutrition standpoint, Hidden Valley meadow fescue has a very high fiber digestibility (see table). This translates to more predicted milk production even though lower forage yield reduces the potential stocking rate compared to other grasses. We were excited about the potential for this grass and consequently proceeded with the steps needed to help it reach market.

Seed production hurdles

When USDA research results in a new or improved plant variety, the USDA usually enters into an agreement with a commercial seed company that acquires exclusive rights to increase seed and take the variety to market. This was attempted with Hidden Valley. But due to poor seed production in Oregon, and the relatively small market for pasture grasses, any interest in the customary options for commercial seed production were eliminated.

But word of Hidden Valley’s superior qualities spread. In 2013, Larry Smith volunteered to plant a Hidden Valley seed production field near Viroqua, Wis., where he runs a beef grazing operation. Shortly after that, the USDA formally released Hidden Valley to the public, meaning that anyone has the right to produce and market Hidden Valley seed without contracts or agreements with USDA or the University of Wisconsin.

Larry Smith harvested his first two crops of Hidden Valley Breeder’s seed in 2014 and 2015. In spite of the fact that there can be no exclusive rights to the variety, two seed companies (Byron Seed and Allied Seed) and a Wisconsin-based dairy cooperative (Organic Valley) have requested Hidden Valley Breeder’s seed from him.

Smith has produced Breeder’s seed at his own expense, but is asking companies to provide research funds to Grassworks through a special agreement based on commercial seed sales. Grassworks is a Wisconsin-based organization that provides leadership and education to farmers and consumers for the advancement of managed grass-based agriculture.

The U.S. Dairy Forage Research Center continues to work with Hidden Valley, conducting additional forage and livestock trials to ensure that the public has good data to make informed decisions. Very limited amounts (not enough for commercial use) of Hidden Valley seed can be obtained from the USDA Germplasm Resources Information Network (www.ars-grin.gov) or directly from the U.S. Dairy Forage Research Center (Michael Casler). Questions about its future commercial availability should be directed to the seed companies. We will be watching from the sidelines, eager to see if Hidden Valley succeeds in the marketplace, the pasture, and the dairy cow’s diet.

This article appeared in the January issue of Hay & Forage Grower on page 20.Not a subscriber? Click to get the print magazine.